How do you define good design? “A good design project is supposed to be explained to your mother over the phone. It is not a question of shapes, forms or finishes. It is a question of what you want to say and what you want to express.” Where it begins. Where it ends. Mathieu Lehanneur questions the serendipitous versus the intended premise of life, rather differently.

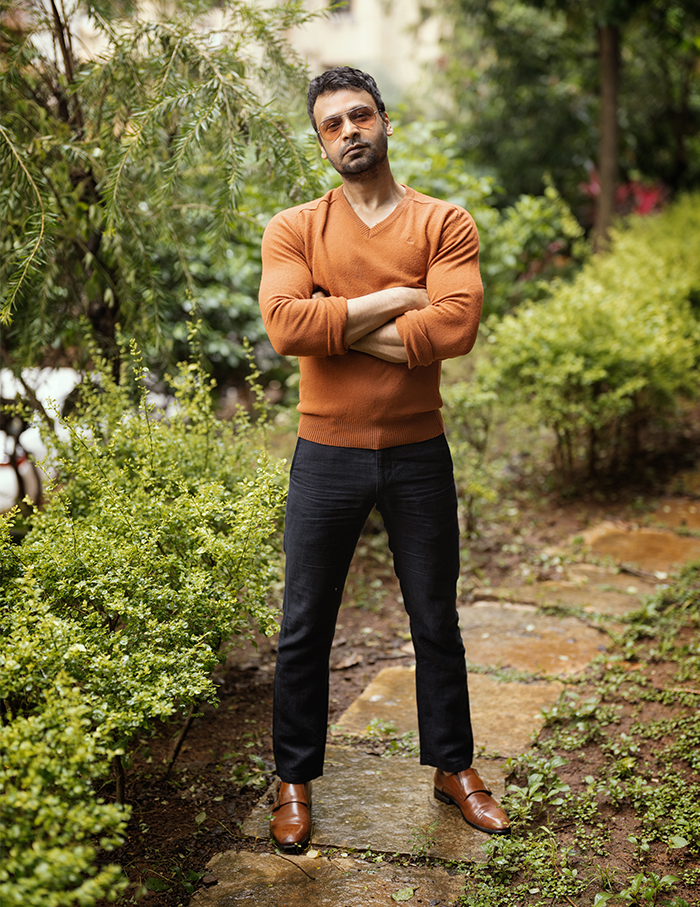

That is, what happens in between it all? An irrepressibly composed yet flamboyant sense of being surrounds the 49-year-old French designer, when we meet him for a long conversation, connected across continents, through our screen. With technology so palpably embedded in that moment, I can’t help but draw parallels between his idea of design in entirety.

Can technology be a bridge to emotional spirituality? Can an object mirror real-life experiences? How can scientific discoveries be an ally to human beings? And that’s when the multihyphenate Mathieu reveals that a few years ago, an elderly Indian couple discovered Mathieu’s Liquid Marble at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. As he was later informed by the staff, they spent nearly the whole day sitting by this vast, polished black marble object — depicting the surreal fluidity of the static sea. “I’m convinced that they were probably living the same experience as my young self sitting in front of the sea.

For me, success is not the question of pieces sold or the money raised, but the experience that people live with an object.”Most recently, Mathieu headlined reports on creating the Paris 2024 Olympics and Paralympics Torch. A momentous time in his book of history perhaps. He was also crowned Maison&Objet’s Designer of the Year 2024. Design, however, wasn’t exactly his plan early in life. “I decided to become a designer very late at 18 or 19-years-old.”

With his works now displayed at top art authorities such as the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York and Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, Mathieu adds, “I am the youngest one in a large family and grew up in the suburbs of Paris. As a teenager, I once wanted to be a doctor, a job that potentially could save a life.”

Soon after, Mathieu discovered another way of creating life. Giving material shape to his thoughts. From 1994 to 2001, he studied at the prestigious Ecole Nationale Supérieure de Création Industrielle. Now a loyal dweller in central Paris, Mathieu recounts spending months of quiet time in Corsica, Southern France, where his father, who used to be a hydraulic engineer, spent his childhood.

Contemplation, clairvoyance go on to become unbending fundamentals of his recent installation at Maison&Objet 2024 titled Outonomy.“This project was to not provide answers but to ask questions.” He adds, “We are ready to live in this type of a house, is the best answer I could get from visitors.”How was the term Outonomy coined? “I wanted this project to work on an autonomous way of living, connected with the outdoors, nature and with being outside of the city. So we combined out and autonomy.”

The installation draped in confident hues of yellow, intertwines function, technology and layers of perspectives. For his other complex yet super-emotional installation ‘Tomorrow is Another Day’ for Palliative Care patients at a hospital in Paris, “I designed a new window in each room with a screen displaying what the sky of tomorrow would look like across geographies and weathers,” which patients during their last moments could see, be connected with…Mathieu, whose design grammar is as technologically informed as his appetite for eccentrically intelligent ideas, moved out of his initial studio recently.

He calls the new whereabouts in the Ivry-sur-Seine neighbourhood the ‘Factory’, “We are in a large, centuries-old historical building, next to Paris. I call it the Factory because we’re producing ideas here and the pieces too. For me, this is also a reminder of Andy Warhol’s The Factory (New York).” With plans to soon reveal his new Pied-à-terre in New York, a universe of his fascinating creations on display, he promptly adds, “In my opinion, even if I define myself as a designer — as a designer, I’m not supposed to make very specific things. Nobody in this world is really able to define what a designer is supposed to do. It is a blur. This allows us to investigate the field of architecture. Sometimes go more into the artistic or the scientific field. Because the question is to not choose a domain, but be more connected with humans and nature itself.”

A sneak peek into Mathieu Lehanneur’s works…

2024 PARIS OLYMPICS TORCH

A once in a lifetime moodboard for the mega quadrennial sports advent, Mathieu Lehanneur envisions the trailblazing torch for the 2024 Paris Olympics and Paralympics, with the material supported by the steel company ArcelorMittal and the frame following equal parts symmetry and curves. As he describes it, “Simple like a hyphen and fluid like a flame.”

HAPPY TO BE HERE

With glass as its primary protagonist, the Happy to Be Here collection of furniture for eccentrically-progressive living spaces, exemplifies the material technique of glass. The console that seems to be floating (but with purpose) against gravity is anchored with hand-blown glass bubble-shaped legs. An oxymoronic display of strength in fragility.

OCEAN MEMORIES

A sea frozen in time and movement, yet as nimble and surreal in its portrayal, Ocean Memories is a part of the Liquid Marble series, also exhibited at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London during the 2016 edition of London Festival. The polished frame wraps the three-dimensional beauty of waves and currents, capturing the physics of solid to liquid transformation.

SAINT-HILAIRE CHURCH

An architectural milestone with a religious identity at its centre, the Saint-Hilaire Church in the old-historical town of Melle, France, highlights the marvels of geology in its geometrical built. The structure, like a box sunk into the sand, is a part of the natural landscape. Lehanneur says, “I imagine that when this ‘box’ was sunk into the ground as if pushed by an invisible, maybe divine hand, it revealed the visible aspect of a mineral and massive form.”

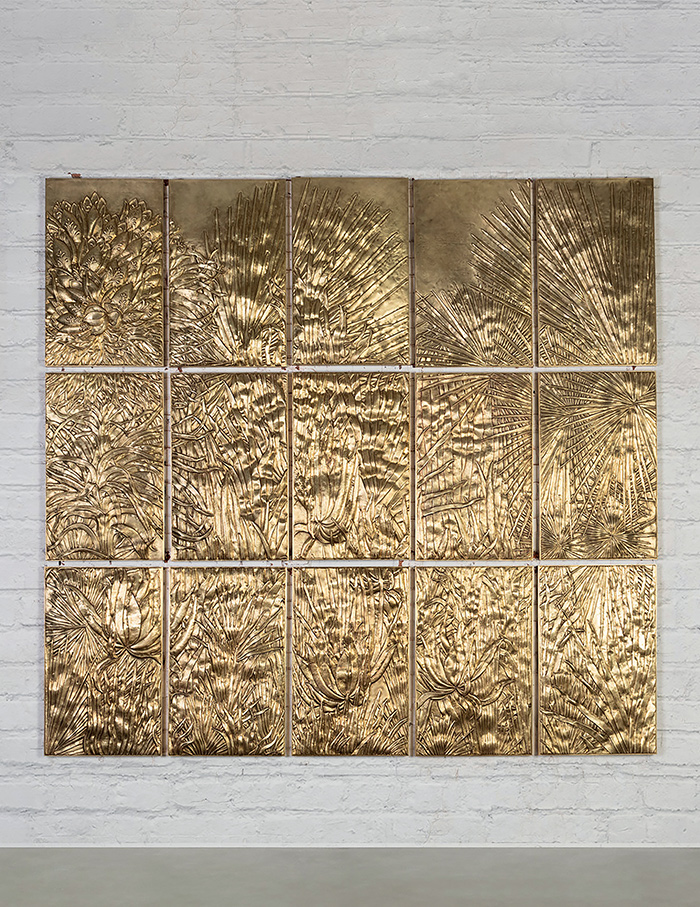

S.M.O.K.E.

Metaphorically and visually, the S.M.O.K.E lamp insinuates a domestic catastrophe, a consequence of fire eruption, gas leaks and suchlike, portrayed through an intriguing shape of explosion with blown glass — shedding light on the environmental impact of substances and their reactions.

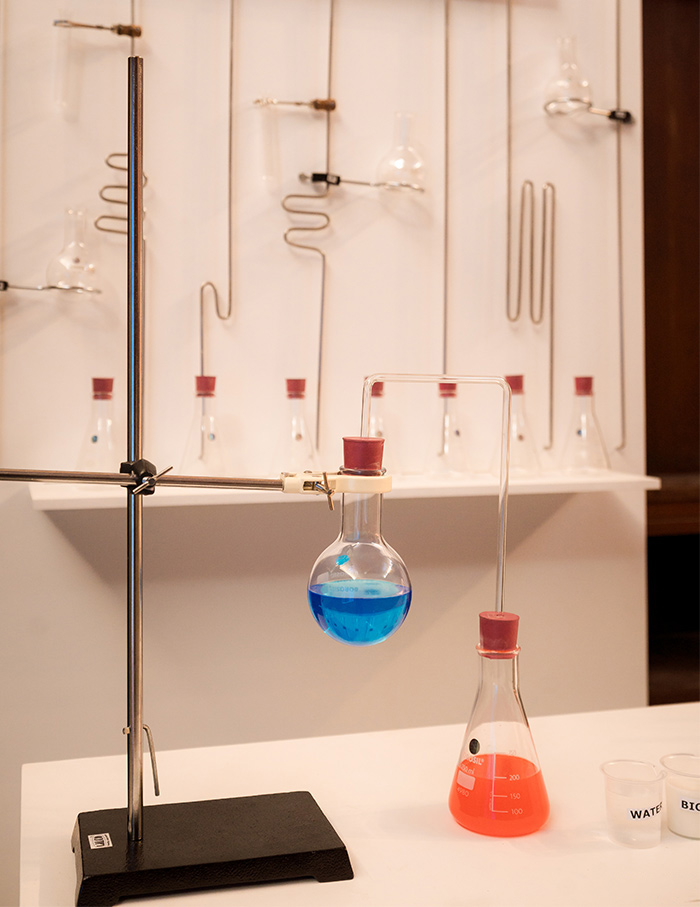

ANDREA AIR PURIFIER

NASA’s discovery of high-level toxic compounds embedded in astronaut’s body tissues due to materials of the aircraft like plastic and fibreglass is directly compared with the invisible emissions of manufactured products inside our living spaces. ANDREA is a living air filter, wherein the leaves and roots, purify and absorb the contaminated air released by these products.