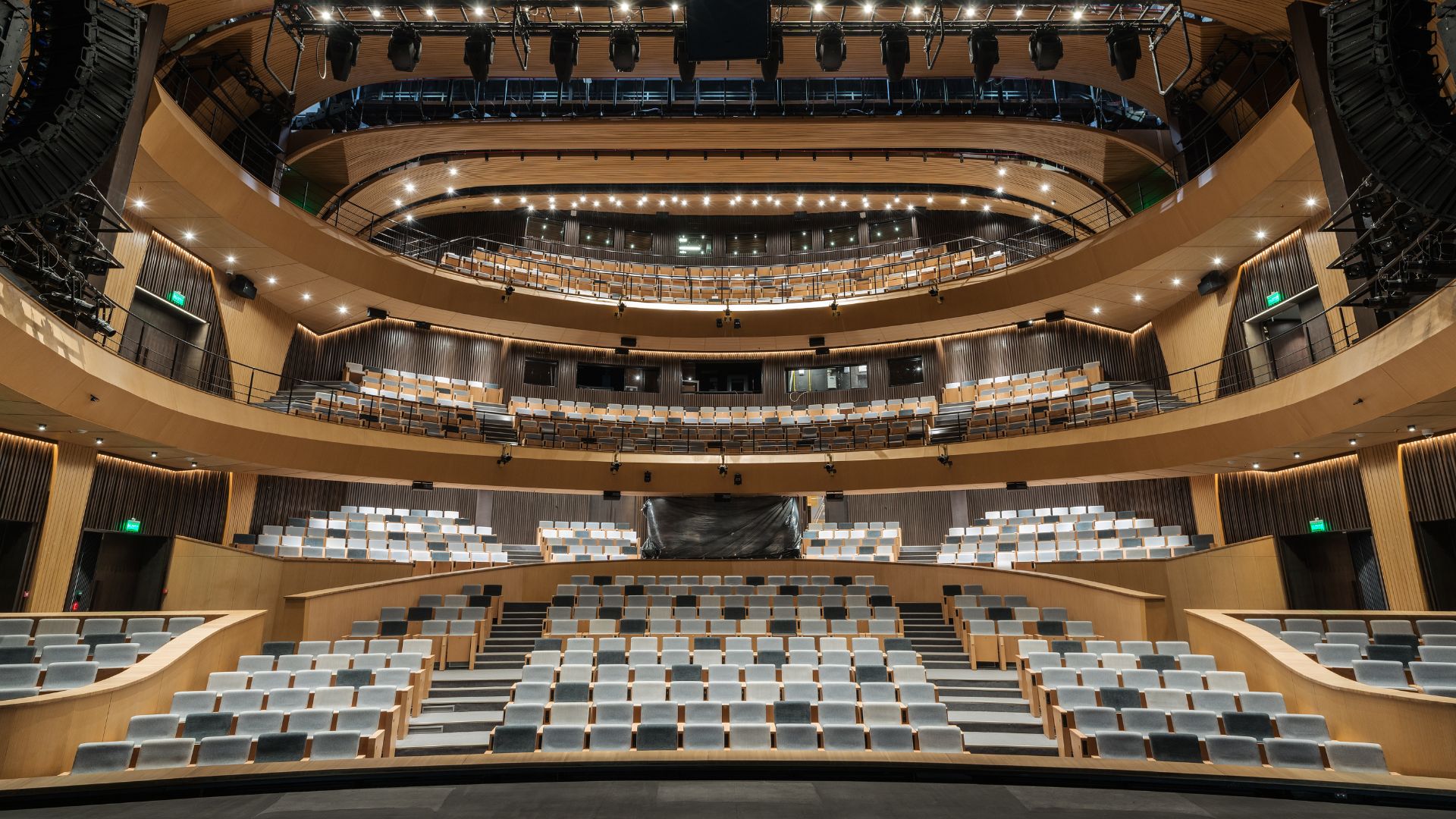

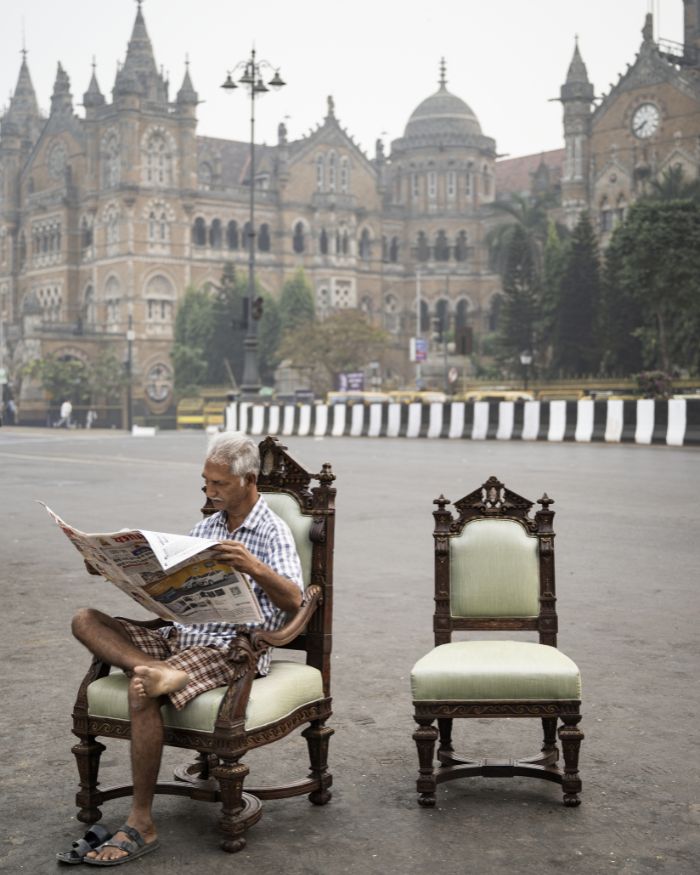

What do two theatres have to say to each other? As I glance outside the window in Kazan, two forms anchor the frigid vista, separated by a snow-laden Millennium Park. Each reflects a time of its own. To the right, the grounded old Galiasgar Kamal Tatarian State Academic Theatre, with its origins in 20th-century Russia; to the left, across Kaban Lake, its counterpart. A shimmering new light of the future. This was where the Kazanysh forum took place, bringing together architects, designers, and thinkers from across the BRICS nations for a dialogue on design. Created by the Moscow-based Wowhaus architecture office in collaboration with Kengo Kuma and Associates, the new Kamal Theatre, at first glance, might seem in stark contrast to the kaleidoscopic traditional town. But a closer examination reveals that the shards of the theatre are inspired by the ice flowers on the frozen lake and the dramatic slope of the old structure.

“This is the structure of the city. It’s a public space where something is happening all the time”— Oleg Shapiro