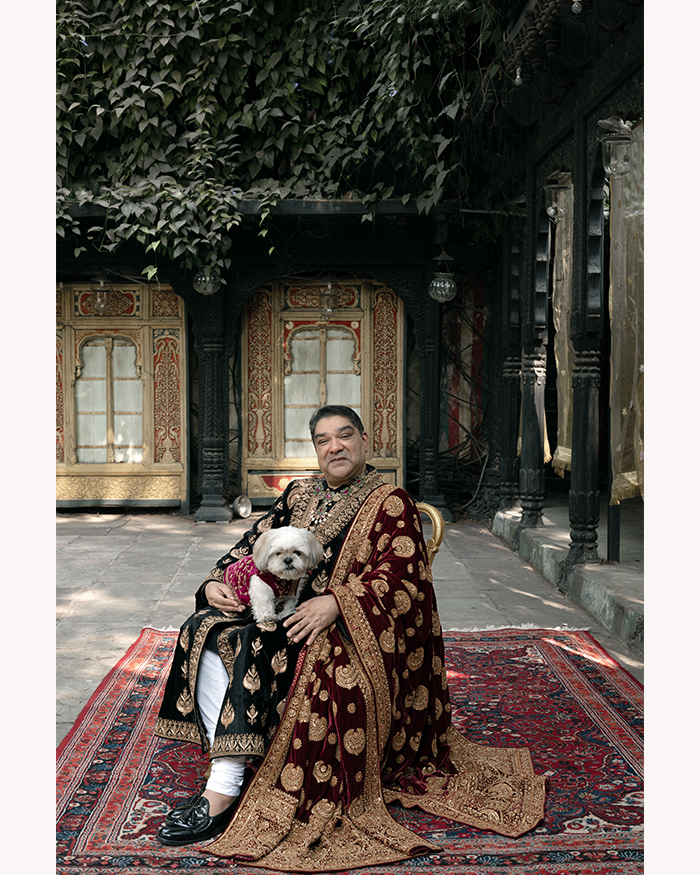

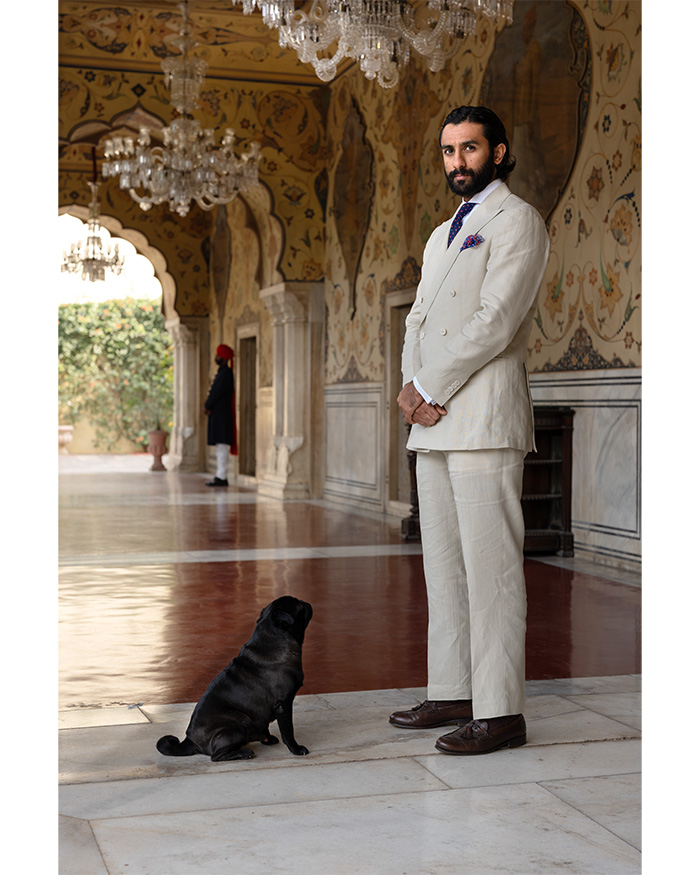

Khadi versus makhmal. This comparison is barely uttered in normal social settings in India. One is quiet and conscious. The other is ceremonial and bejewelled. But inside the Hutheesing Haveli, khadi and makhmal are two sides of the same coin, especially when Umang Hutheesing, the 11th-generation scion of the Hutheesing dynasty, drapes it. But it is not as much about the fabric or the presence he wears, as much it is about the power and influence his centuries-old lineage accords him, an undercurrent that exists around and within him, in solitude and in public. In Khadi, his regalia shines bright through the grainy but poised ridges of the fabric. It is silent and intentional. When he wears makhmal, regalia reappears. It is at once, authoritative. When we meet him, Umang is clad in red, black and gold, his favourite colours that to him embody unfiltered Indian maximalism — his sense of utmost originality. “I’m wearing a Mughal Chogha (a long-sleeved robe worn in the royal courts),” he declares, proudly so, with a glimmer of reminiscence passing him by, if only for a second.

No set of questions or research can prepare you for the lessons in intellectual maximalism that this visibly obscure haveli in Ahmedabad opens up to. We’re inside one of the oldest residences in the city, a place that has seen some of India’s most prominent cultural, political and diplomatic currents converge. It belongs to the Hutheesings, the historical jewellers, mercantile family (the mahajans) and bankers to the kings, whose strategic ties intertwine as far back as with the Mughals and Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, and to lawful pedigrees with Jawaharlal Nehru and Rabindranath Tagore. His great-grandfather, Magan-bhai Hutheesing, established one of the oldest design companies in Asia in the 1880s, The Hutheesing Design Company, alongside virtuously leading The Ahmedabad Wood Carving Company with American interior decorator Lockwood De Forest. As destiny would decide, Magan-bhai took his acumen for Indian design across borders, even becoming a business partner to the founders of Tiffany & Co. back in the day.

Maximalism resides in every verse and dialogue with Umang, the 61-year-old custodian of Indian maximalism, who begins to recount the changing eras of the country through its kingly, imperial and modern democratic histories, almost as instantly as we ask him what his idea of Indian maximalism is. “To understand the concept of Indian maximalism, you have to start with history. And I’m profoundly proud to say that my family has determined and influenced Indian history for a very long time, dating back to the pre-Mughal era.” Umang is not just privy to the responsibility of his family’s material lineage, but in his everyday life, he’s also inextricably tied to the extreme swells of the sentimental archives that have travelled many hundred years of generations to co-exist around him in abundance, brushed with a quiet authority that can only be recognised, not announced. He views power and influence as an extension towards nation building, which begins with compassion and a sense of being private. That afternoon of our meeting, Umang wears the figurative garb of a generous narrator of Indian maximalism and its facets in Ahmedabad. The haveli is struck by the daylight. In parts, the light softly consumes the aged silhouettes of its facade walls and time-preserved sculptures. A lone baithak sits on an antique European mosaic floors. But one must not call this haveli a museum; decorative terms like this often seem unreliable and reductive, especially when history still continues to live, breathing through the accumulation of black and white photographs pinned on the walls inside, revealing Nehru, Gandhi, Tagore, Kings, Queens, ministers and personalities of the past; an evidence that maximalism is simply memory

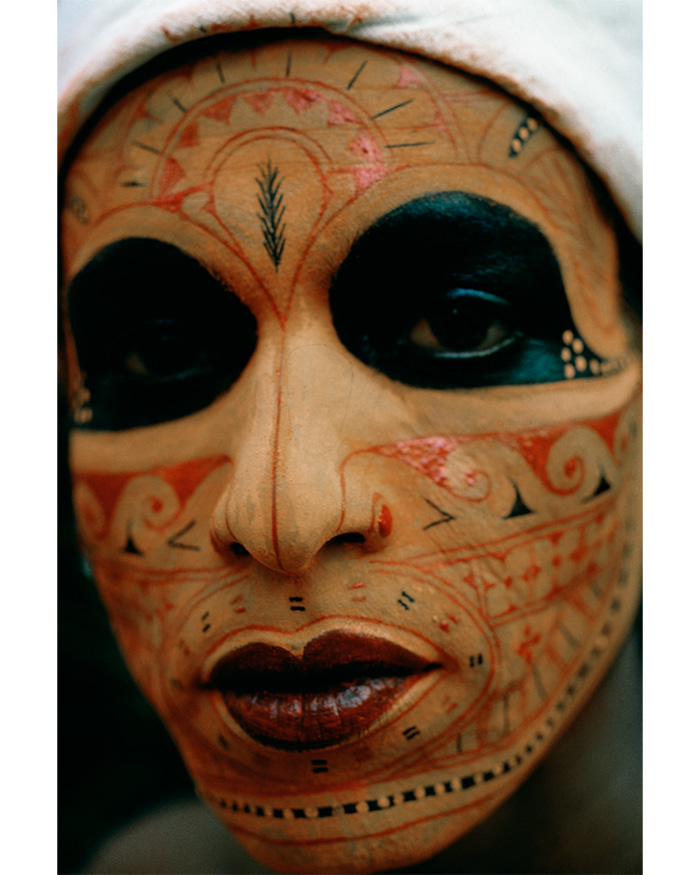

“Even privately, we’re not ostentatious or loud people. Why should we be? God has been kind to us, and only a fool, will mistake simplicity to be the lack of resources and humility to be the lack of power,” asserts Umang. Maximalism in India has long been misperceived as decorative indulgence, when in fact, it lives on as cultural evidence. Every object, textile, motif and architectural gesture that appears too much is a record of something — one’s life, an encounter, an influence, a moment that refuses to be erased. In a country shaped by centuries of trade, patronage, political movements and plural belief systems, aesthetic density is not a byproduct of taste but the natural consequence of continuity. At Hutheesing’s, continuity’s first origins are found centuries ago, beginning with their ancestor Shantidas Jhaveri’s influence on the Mughal Empire through his command on money and jewellery that would often manoeuvre who stays in and out of power. “At that time, it was my ancestors who signed a treaty with Humayun to fund the empire on one condition that Jainism would be protected by God’s decree and we would control the treasury.” And so, “Mughals didn’t finance us, we financed the Mughals.” One cannot speak of the Mughals at the Haveli without witnessing the frames of original Mughal-era resham (silk), makhmal (velvet) and ceremonial zardozi preserved indoors. Following Umang’s lead further, another section of the haveli is revealed through a second courtyard that assimilates a similar reality but of a new century, where his eponymous label Umang Hutheesing archives and undertakes the retelling of royal Indian costumes. But he rejects being called a textile expert. “I’ve gone to no textile or design school. My expertise is Indian culture. I’m a cultural impresario.” Back in 1997, Umang’s invitation to the Met Gala, when India was still opening up to the world’s red carpets, led him to assert India’s sartorial history picked straight from his personal collections. “What did I wear? I wore the original coronation outfit of the Nawab of Awadh to the Met Gala. You talk of OG, that was OG.”

If you think about it, there was never a single word in India that defined maximalism. The idea was intact though, through concepts of sajawat, shringar, alankara, hastashilp, vaastukala and virasat. Virasat translates to inheritance, before which comes history and the power held through valuables and materials. But is that all maximalism is reduced to? “Real power comes not from the accumulation of wealth, but from being able to share it,” asserts Umang. Sheth Hutheesing, descendant of Shantidas Jhaveri, commissioned the Hutheesing Jain Temple (derasar), near Dilli Darwaza in Ahmedabad, at the height of the Gujarat famine in the 1800s that displaced lakhs of people, turning temple construction and devotion into a form of civic support for the lakhs of displaced migrants, kaarigars and workers. As of 2025 we’re told, the family’s trust for the last 600 years has been managing over 1200 temples in India. “My legacy gives me honour. And my legacy is about giving, not about collecting.”

“At that time, it was my ancestors who signed a treaty with Humayun to fund the empire on one condition that Jainism would be protected by God’s decree and we would control the treasury.”

- Umang Hutheesing