I had three hours before I flew back to Mumbai. Time was of the essence. There was little room for etiquette, and even lesser for pondering longingly at the white walls of the booths. (The latter I hear being the recommended course of action for engaging with art.) In the slew of perfunctory hellos and seeing old friends, how could I cram the most into my first encounter with the much-revered India Art Fair? I did the only logical thing there was to do. Set strict timers and stretch my legs like a pro-athlete. And by 12 pm, I could run the entire length of the Boston Marathon on sheer enthusiasm alone. In the short while I was on the ground, I met a host of people from different walks of life, each with their own views on the IAF (including a well-known kleptomaniac whose identity shall remain redacted).

On a more serious note, my first conversation was with the renowned gallerist Mamta Singhania, founder of Anant Art Gallery. With decades of experience behind her, she sees the fair as an important site for discovering galleries from across the world. From Bangladesh to London, the world had clocked in at what appeared to be the event of the season. Interestingly, before the IAF, my first stop had been her recently opened gallery in New Delhi. While the scale and experience of the four-storey space are unmatched, mindful curation ensures that the booth still offers a well-rounded sliver of what the gallery stands for. The presentation included the works of Aditya Puthur, Alexander Gorlizki, Arti Vijay Kadam, Dhara Mehrotra, Digbijayee Khatua, Laxmipriya Panigrahi, Nataraj Sharma, Puja Mondal, Sharmi Chowdhury, Temsüyanger Longkumer, Tito Stanley SJ and Vikrant Bhise.

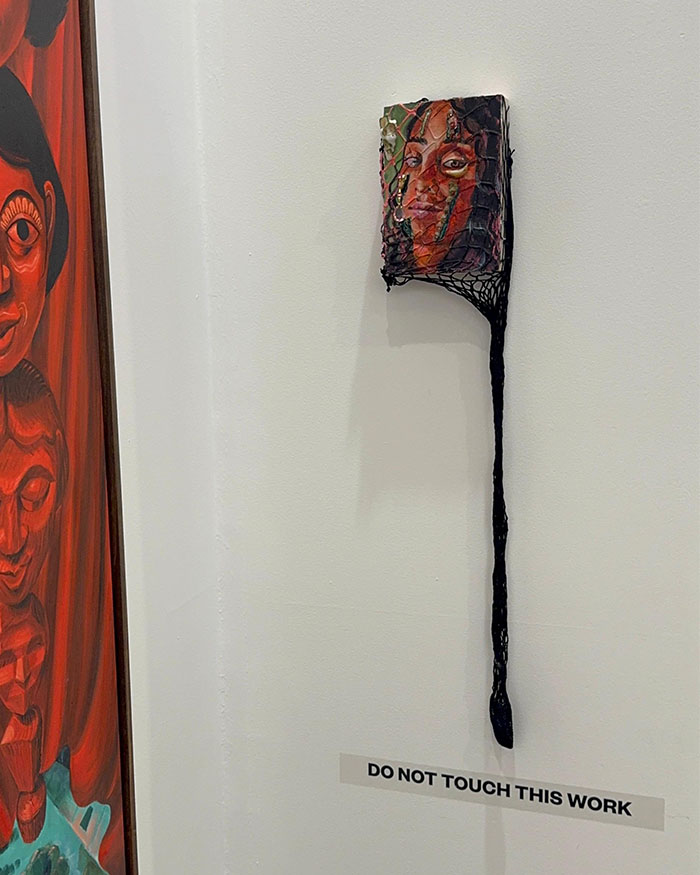

"It is people who occupy more floor-space than the art itself. Taking mirror selfies, making room for conversations and flocking to find the best food. You will find the difference between people who are resisting the urge to touch an artwork and those who feel entitled enough to do so"