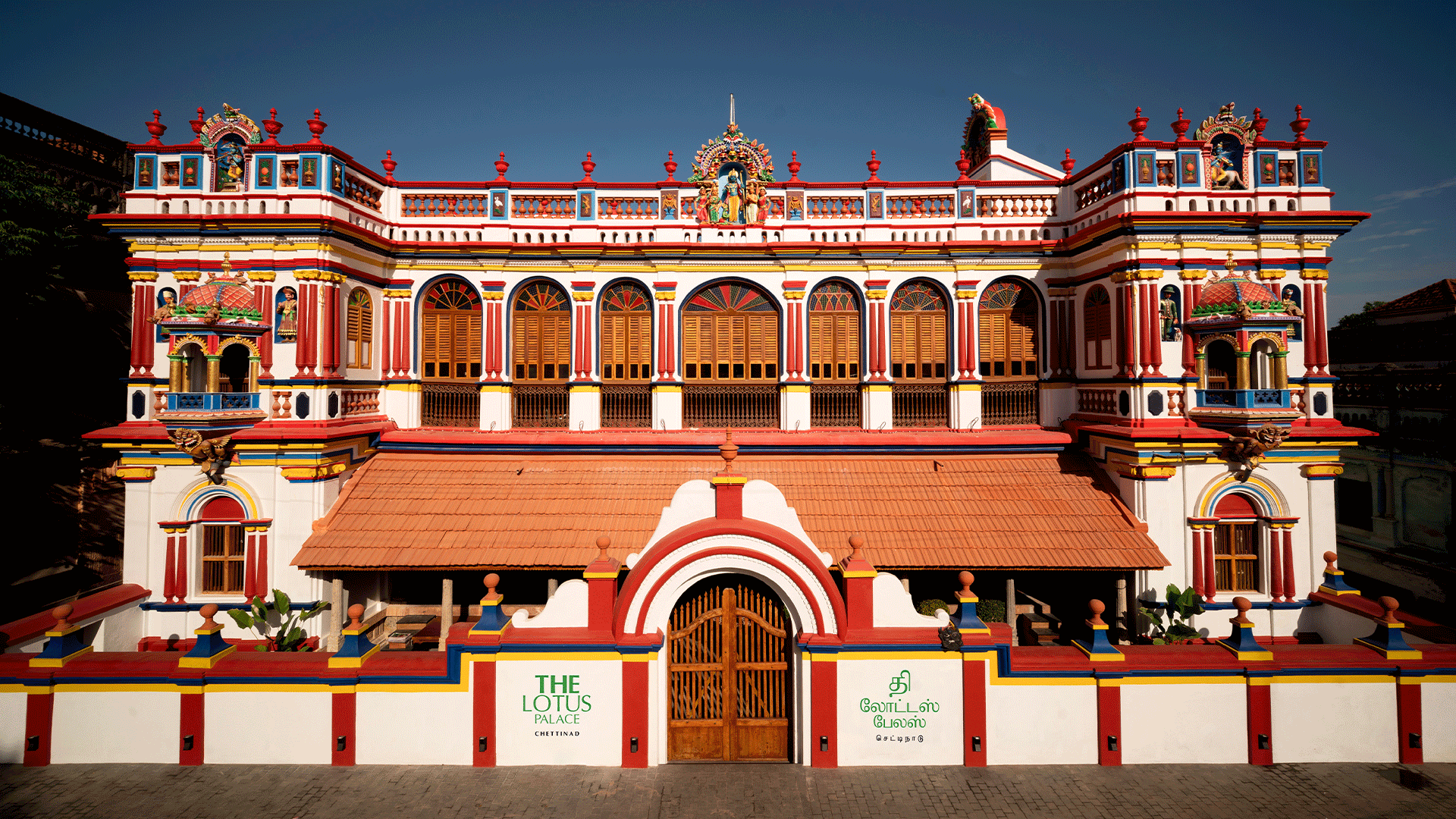

All palaces, at their core, are anthropological experiments in people, power and prosperity. To see them merely as architectural objects, however grand, is to miss the context that gave them meaning. THE Lotus Palace in Chettinad by THE Park Hotels is not, in truth, a palace at all but a 230-year-old mansion whose owner once held royal ties. Its very name is a provocation, suggesting grandeur while hinting at the circumstances that positioned a mercantile village as a stage for power, trade and ritual.

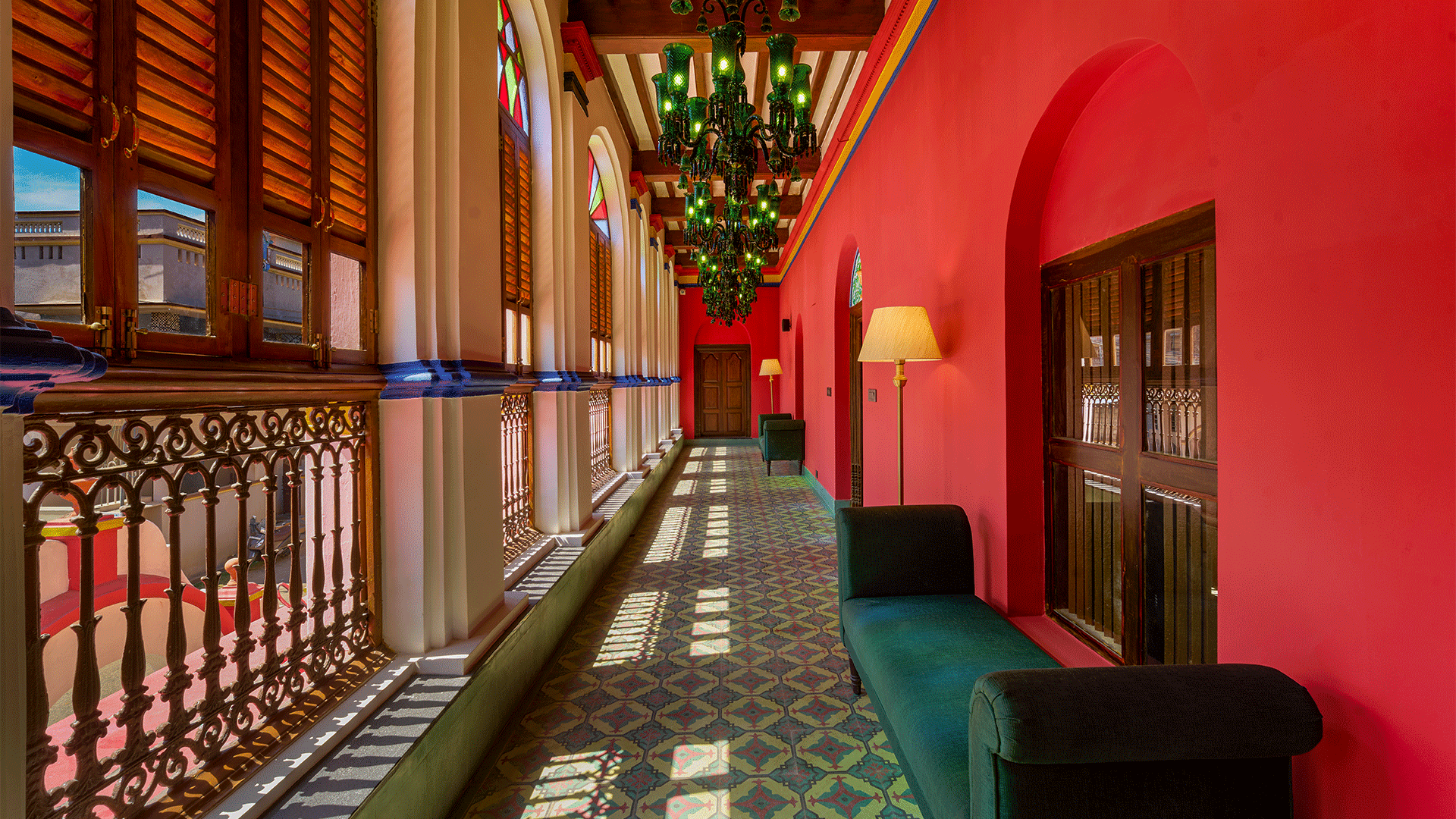

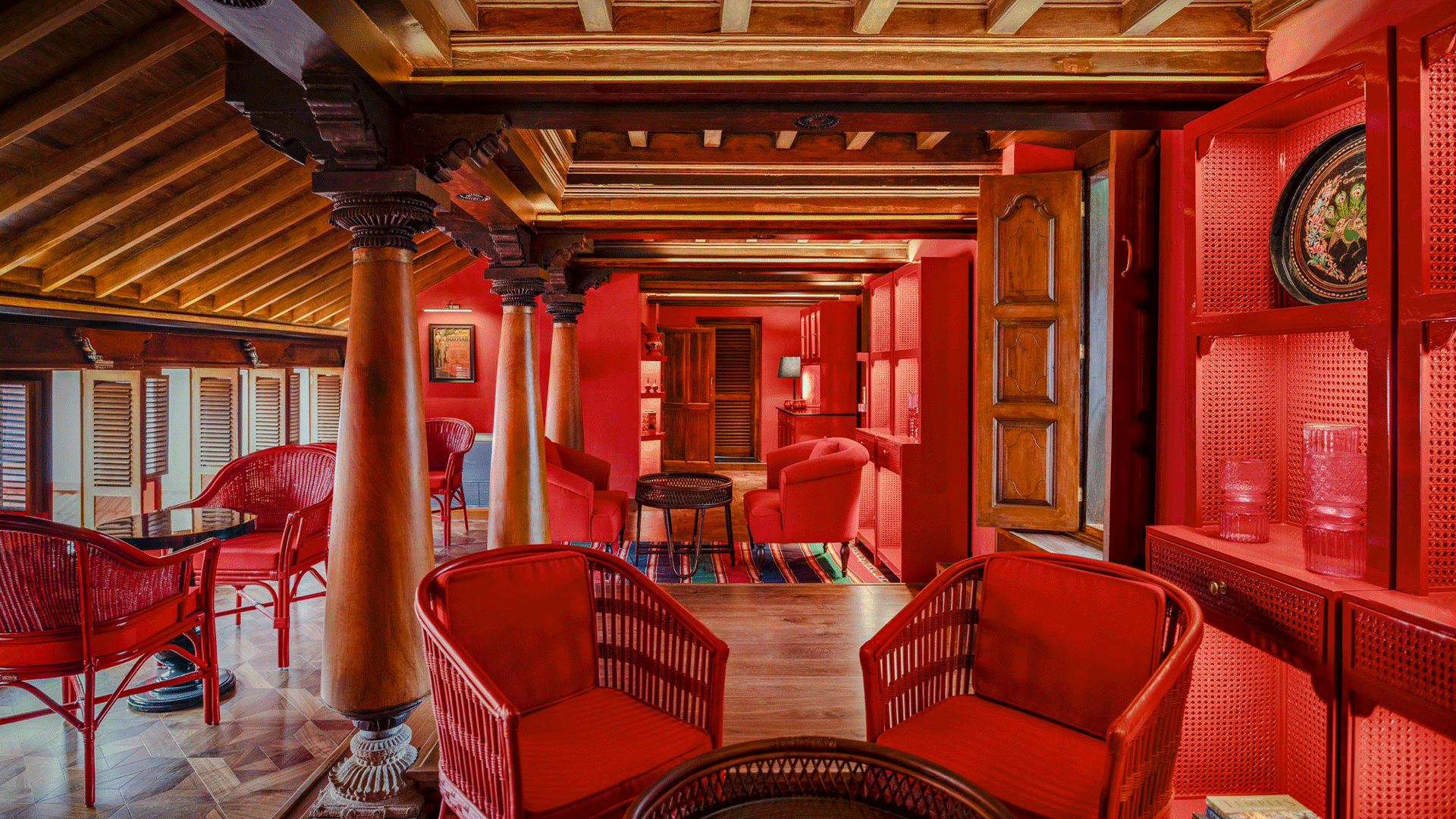

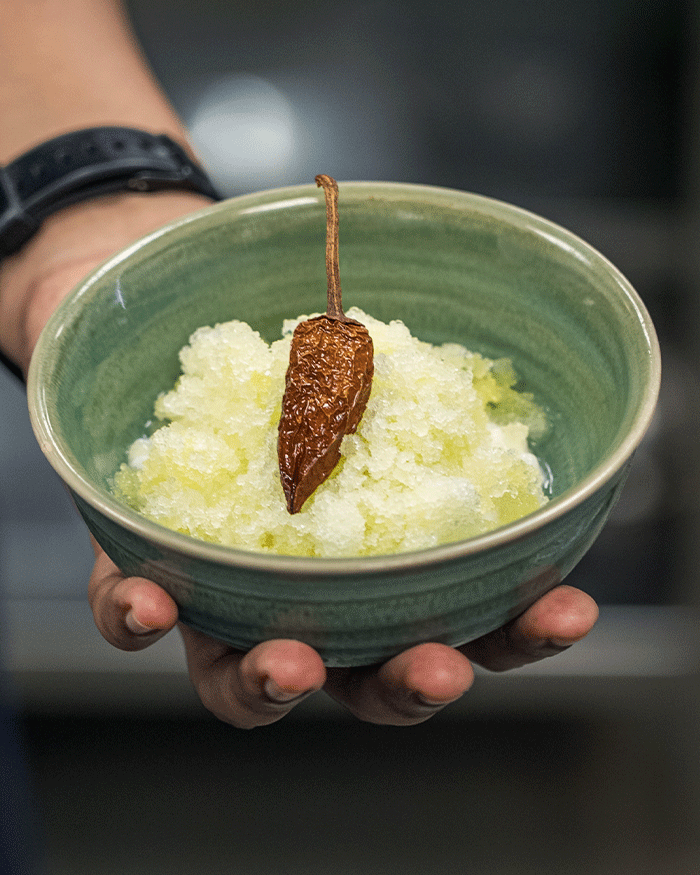

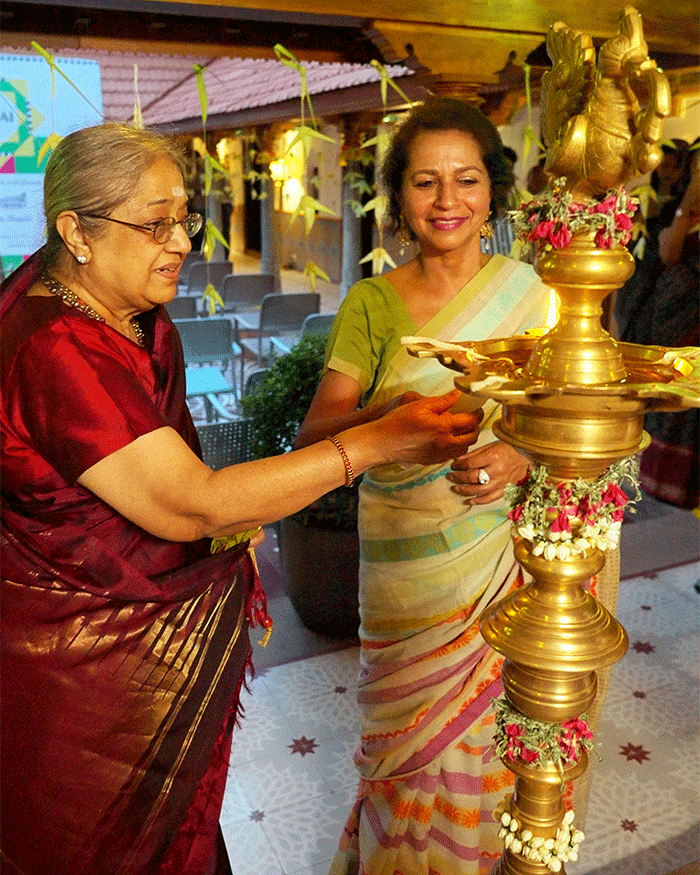

Restored by THE Park Hotels, it embodies this layered history and invites one to confront its contradictions. The mansion itself is undeniably beautiful, yet its truest splendour lies in the culture it nurtured — the lives, rituals and exchanges like the Ram Katha that once animated its courtyards during Navratri. To understand the world it belonged to, and the life it shaped both within and beyond its walls, one must experience it directly. The Suvai Food Festival, a three-day celebration of heritage and cuisine, curated by THE Lotus Palace in collaboration with The Bangala, Visalam, Chettinadu Mansion, and Chidambara Vilas, became the perfect entry point.

“We employ people from the area, we celebrate local food, and we offer authentic experiences. Many of our staff have worked here for generations, and by keeping them employed in their own village, we help preserve the heritage of the place”

Priya Paul, Chairperson of Apeejay Surrendra Park Hotels