As a designer and an architectural conservationist, I have long been drawn to the layered beauty of India’s crafts — their ability to transform material into meaning and ornament into philosophy. “Art in India,” wrote Ananda Coomaraswamy, “is religion expressed through beauty.” It is from this profound vision that India’s maximalism arises as plenitude, not excess. It is the visible pulse of a civilisation that has always sought fullness rather than restraint.

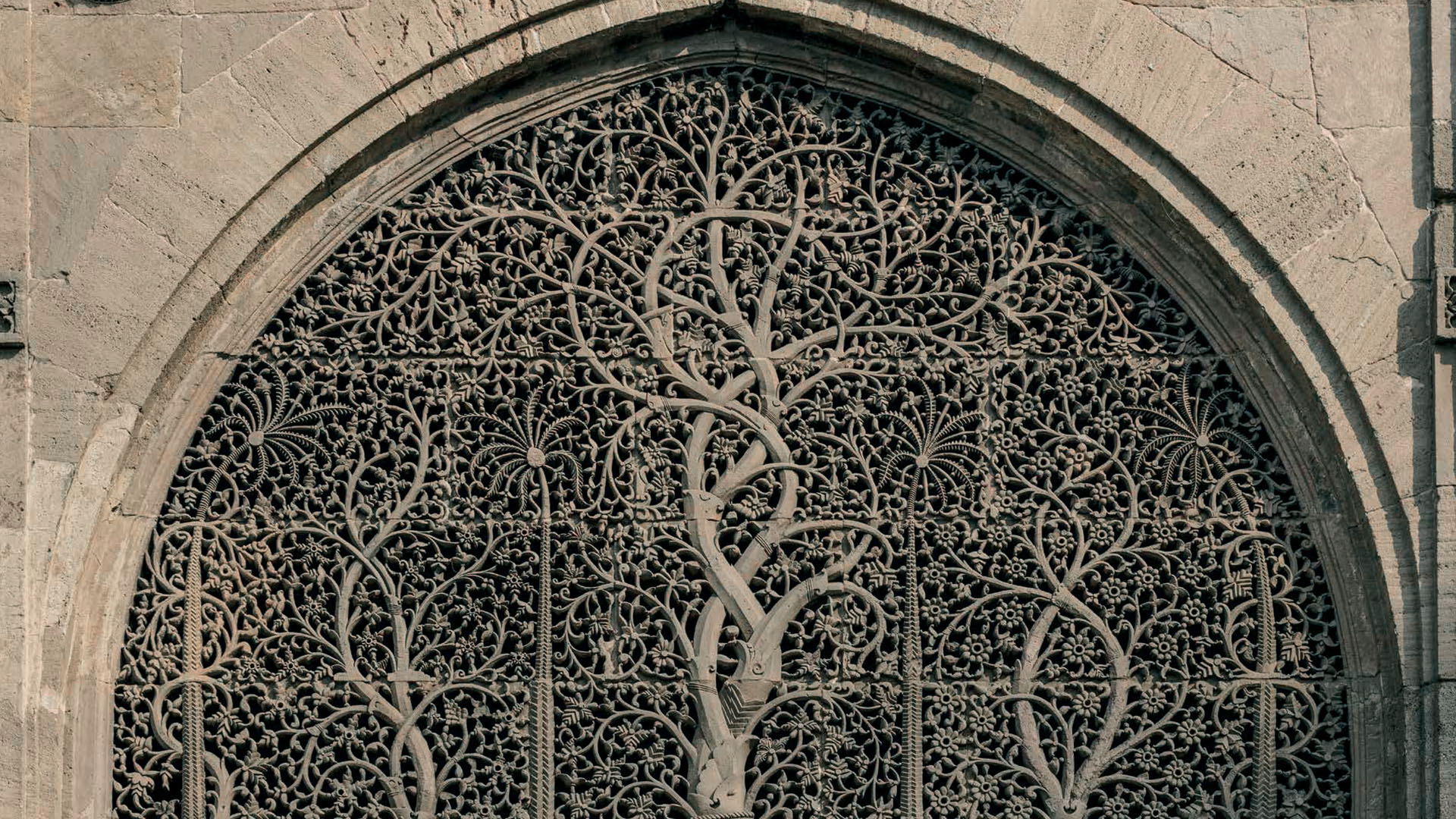

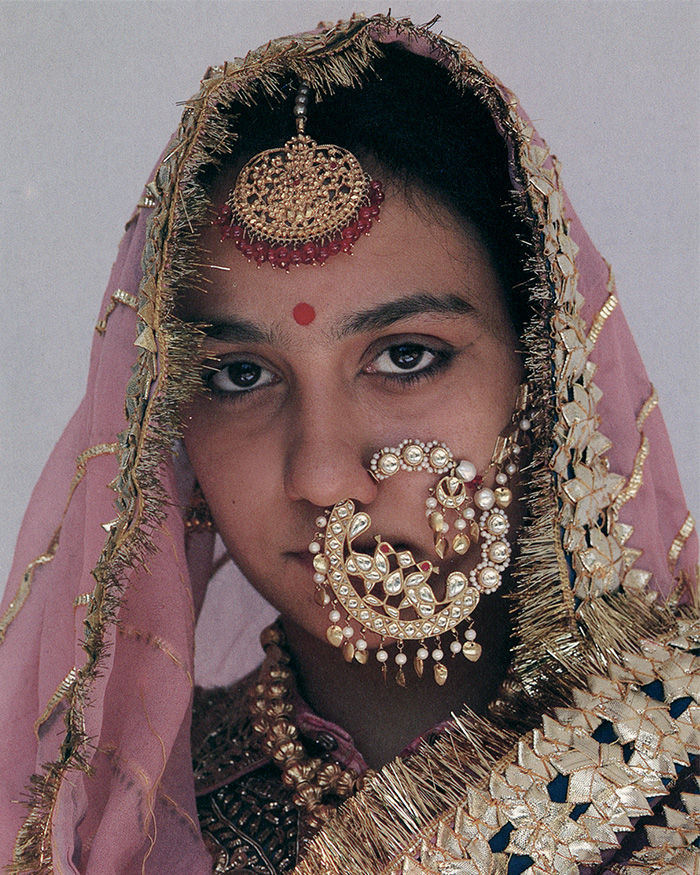

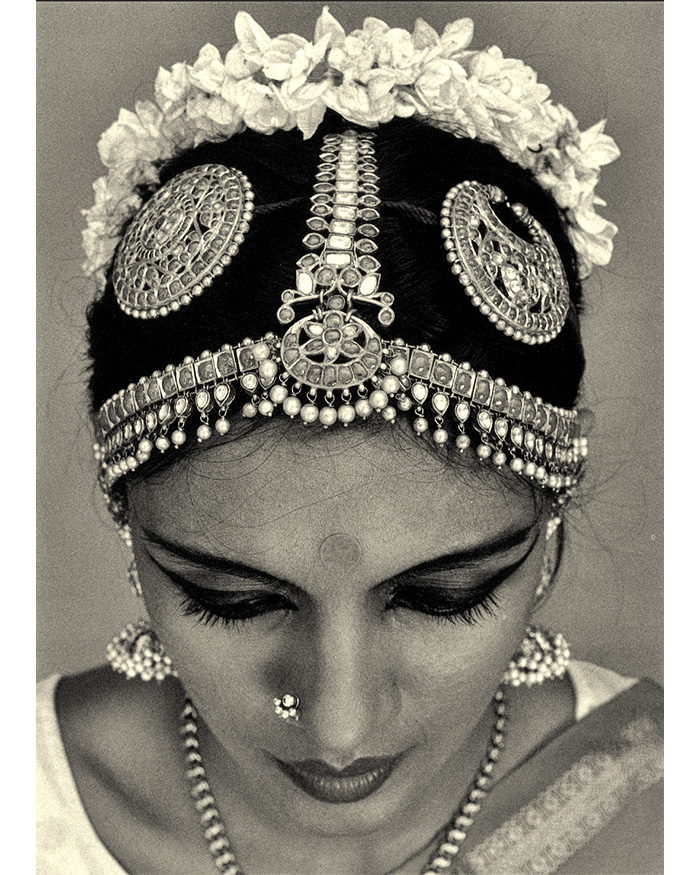

AL Basham described India as “the wonder that was,” and indeed, its crafts — whether woven, carved, beaten or inlaid — form the grammar of that wonder. From the metaphysical geometry of temples to the translucent fineness of Jamdanis and the lustrous textures of Kanjeevarams and Banarasi brocades, from ritual vessels and temple jewellery to the lyrical stonework of jalis and jharokhas — each reveals a harmony between the sacred and the sensual.

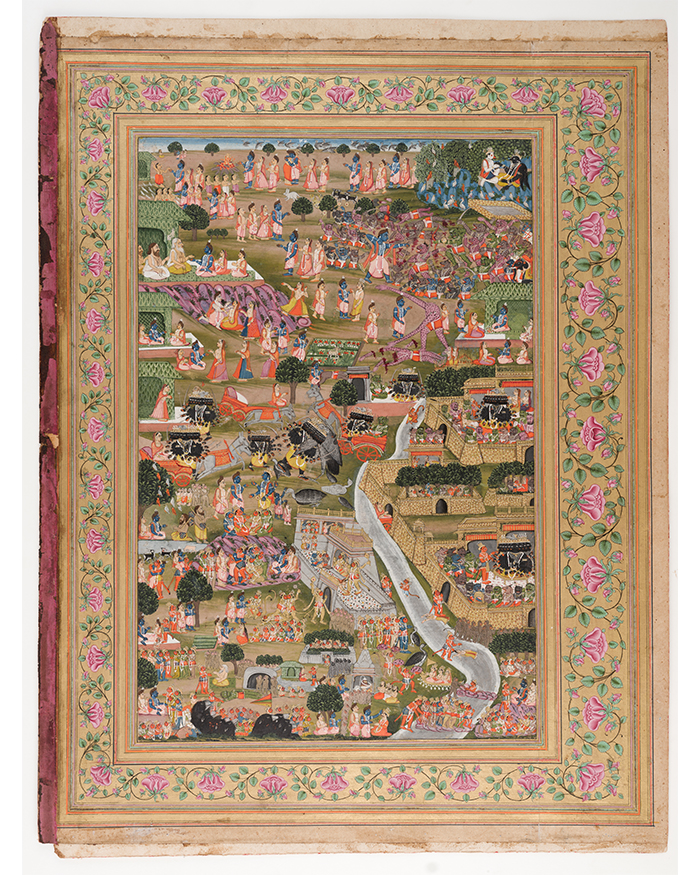

Dr Irawati Karve reminded us that the craftsman “worked not for fame but for dharma,” his or her labour, a meditation on order and devotion and Raja Rao, ever the philosopher, wrote in The Serpent and the Rope that “India is not a country but a metaphysic”, dealing with the very nature of existence, truth and knowledge. Nowhere is this truer than in her crafts, where philosophy takes form through the human hand. We are a maximalist society. More than any other country in the world, we have 240 million craftspeople. Akhtar Riazuddin’s History of Handicrafts: Pakistan-India is widely cited as a thorough and seminal survey of subcontinental crafts. In this work, Riazuddin asserts that the tradition of handicrafts in the subcontinent cannot be seen merely as neutral folklore or marginal cottage industry — instead, it is deeply interwoven with political, religious and cultural currents across eras. She emphasises that Muslim patronage, especially during the Sultanate and Mughal periods, played a pivotal role in elevating crafts — not just in encouraging artisans, but in shaping styles, motifs and establishing institutional support like workshops, guilds and royal commissions. Therefore, to understand the evolution of regional crafts in the subcontinent, one must trace how external influences, local materials and changing socio economic conditions intersected with artisan agency.

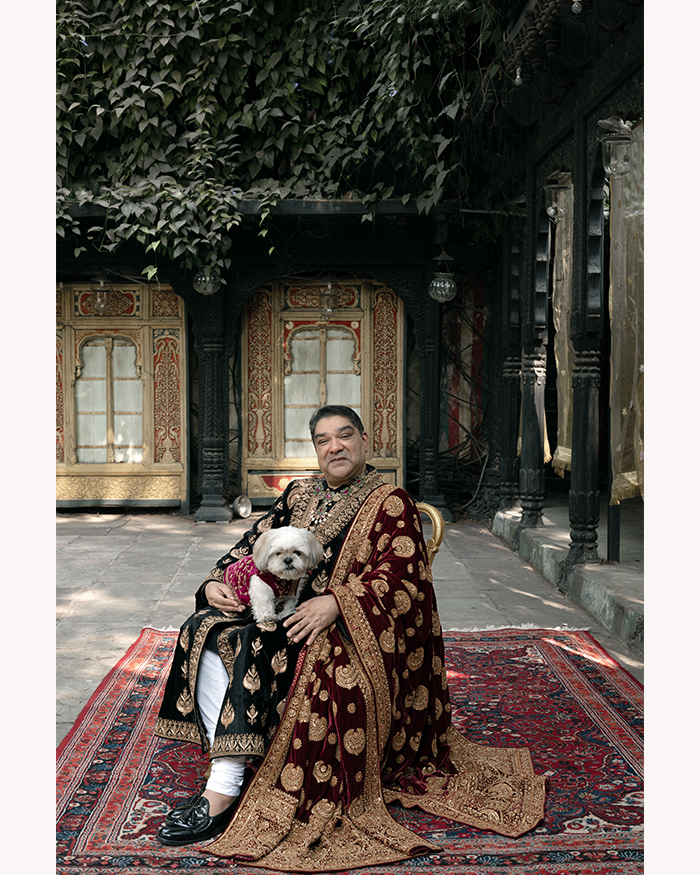

“Across the subcontinent, the jali and jharokha are symbols of India’s maximalist imagination”