Produced by Mrudul Pathak Kundu

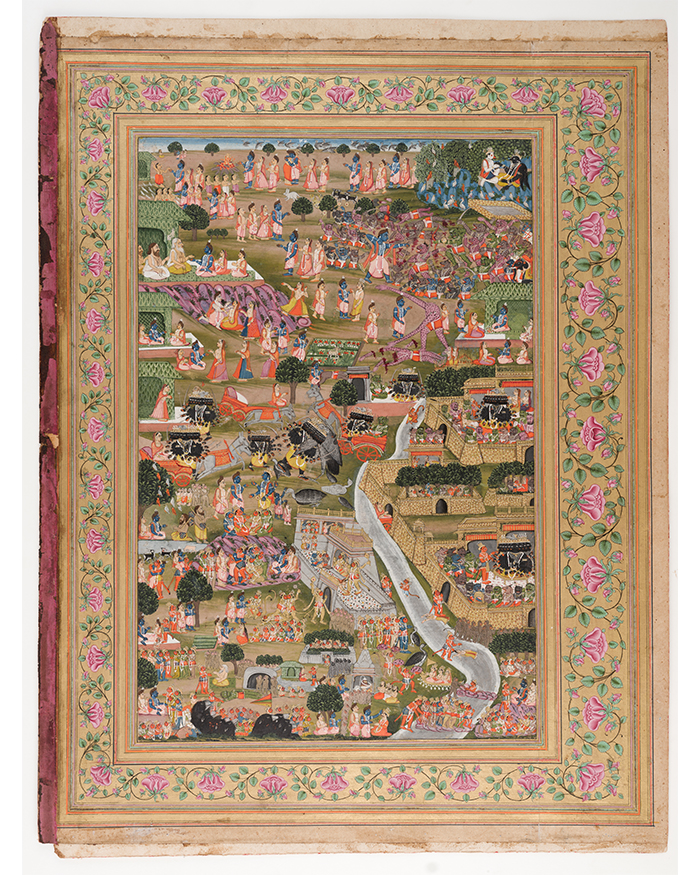

When I look back at my childhood, often spent with my grandmother making papad and achaar, what remains with me is not just the taste but the process itself — the choreography of women working under the winter sun, our palms dusted with flour, the dough kneaded in wide paraats, papads laid out on the terrace, chillies slit and salted for achaar, fingers stained with turmeric and the scent of crushed spices in the air. I used to witness this pattern of maximalism every November. In a traditional Indian rasoi, maximalism is omnipresent. It is the large reserve of utensils (colloquially called bartan) that make up a kitchen’s library. It is seen in the assortment of masalas, herbs and condiments that command shelves and cabinets. It lives in the thali lined with katoris, each carrying different textures, colours and flavours. Maximalism in an Indian rasoi is also the many hands at work, almost obsessive and completely disciplined at every step of culinary processes in the country.

I was born in Calcutta, but by the time I was 10, we had moved to Delhi, my naani to Mumbai and my aunts around the country. One thing that remained untouched by geography or time was our winter ritual of making papad and achaar. In India’s grammar of abundance, this was my family’s version of maximalism. My grandmother would journey from Mumbai to Delhi with all our aunts in tow. Our terrace would become the theatre for the papad and achaar to slip into a methodical performance. I’d take the lead as the head helper. Papad and achaar, a household name during every meal, are two of the oldest, unconquered protagonists of every Indian thali. One is unmistakably crispy, salty and umami; the other is spicy or sweet, fermented and unapologetically fragrant. Papads drying in long rows with delicate but solid glass jars of achaar sun-soaking in the peak afternoons — it is this formulaic, lived-in act of preparing endless supplies of papad and achaar, which tells me that Indian food doesn’t need spectacle to be maximalist. It is already ingrained into our everyday routines. Big paraats filled with dough, moong dal, hing and black pepper for one batch, and another variety called lapad, swathed with red chilli powder for the grown-ups. Papad has always been deceptively simple: a mixture of lentils, spices and salt kneaded to a dough, rolled impossibly thin, sun-dried and perfected over centuries.