Produced by Mrudul Pathak Kundu

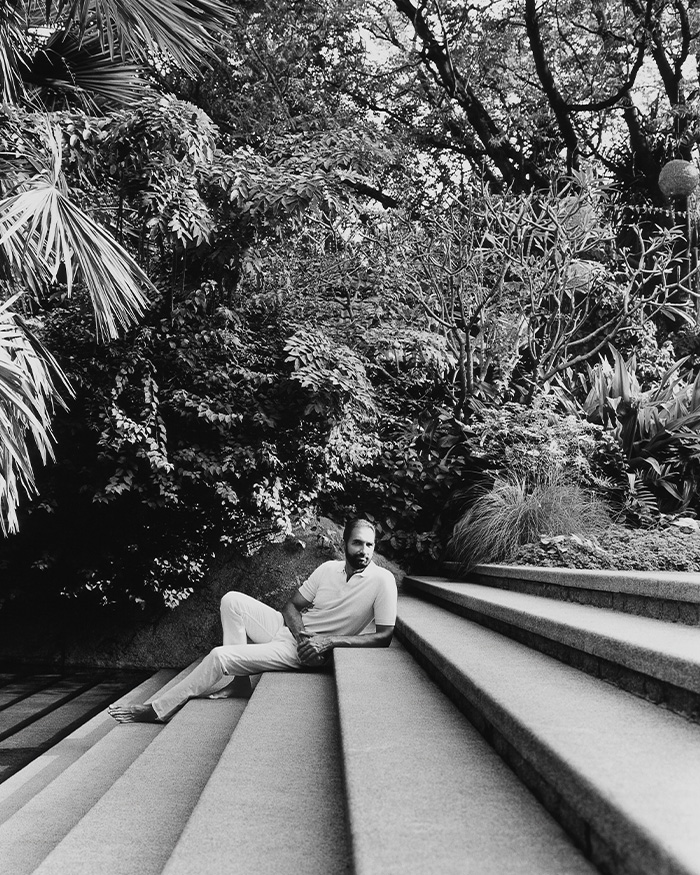

My little gripe with Nozer was simple: the world was missing out because one man was reluctant to share his work and experience. I wanted access, but he had chosen absence — not out of arrogance, but intention. Six months after a 7 AM meeting with Nozer, and a trip to his home in Alibag, I realised that what I saw as withholding, he saw as integrity. He is a man dedicated to his craft, unapologetic about his methods, and exacting in his beliefs.

At 72, Nozer remains a paradox: fiercely private and wholly uninterested in legacy-building. For him, media profiles, like this one, are unnecessary. And yet we are here, at 7 AM in his office as he asks Mrudul Pathak Kundu, Editor, ELLE DECOR India, “So, why do you want to write about me?” Mrudul replies with a question, “Why not, Nozer?”

“Do what you want.”

“This is what I want.”

“Fine.”

“Fine.”

They both look at me, and I take a deep breath and prepare for what is coming our way. Nozer is a tough man — a stickler for perfection, punctuality and precision. His nononsense demeanour is what makes him intimidating and endearing in equal parts. Larger than life, incredibly witty and armed with a delightfully inappropriate sense of humour, you’ll be laughing with him, and also be slightly scandalised at moments. Six months later, I discovered his streak of spontaneous madness, which only makes us fall in love with him all over again. Cue: Nozer jumping into his bathtub in Alibag, daring us to click. Mrudul did not hesitate. “Baji, let’s shoot,” she smiled at our photographer, Bajirao Pawar.

Let’s return to objectivity and rewind. When Mrudul told me that Nozer had agreed to an interview, I imagined a coup: a rare, first-of-its kind tell-all feature from this elusive and reclusive architect of India. Two years ago, when he presented an EDIDA, we could barely write his short biography. I assumed I would get great takeaways, insight into his mind, and a design doctrine. And truth be told, I had not seen much of his work. So we begin at the beginning of his career, where it all began for Nozer.

“Sustainability is a deep and all encompassing subject. If I’m using a sustainable material but importing it from halfway across the world, it’s counterproductive” — Nozer Wadia