It’s about time the gaze of art shifted towards the Global South. Sharjah Biennial’s 16th Edition navigates the inherited knowledge and cultural milieu of distinct narratives that shape it. The Biennial’s multivocal framework engages over 200 new commissions and nearly 200 participants.

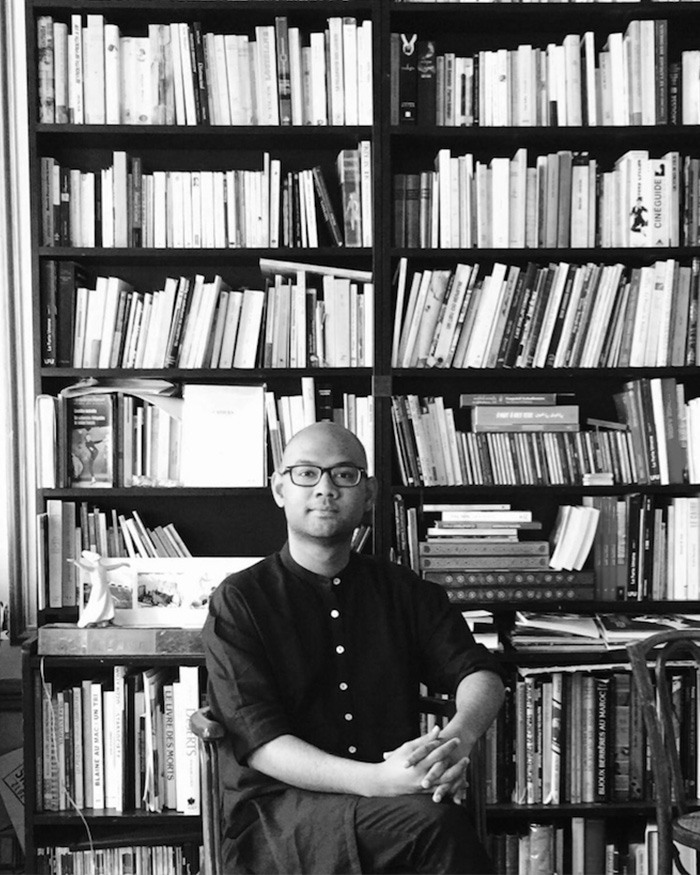

We speak to Natasha Ginwala, a curator at the biennial, to understand what informed her vision. Natasha delves into the curatorial ethos, interdisciplinary dialogue and political urgencies that shape to carry and its evolving extensions.

What is the focus and meaning behind the title to carry?

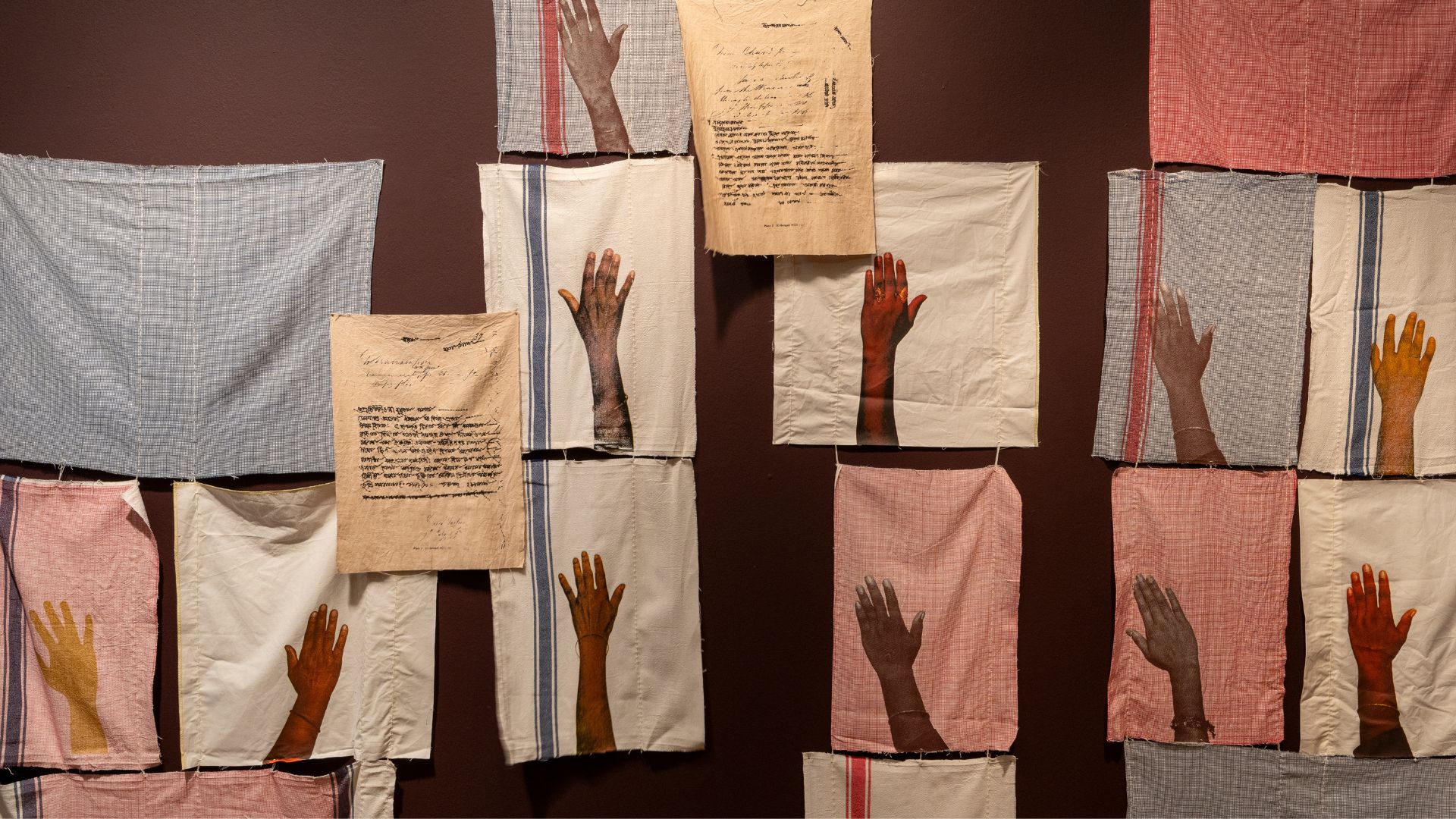

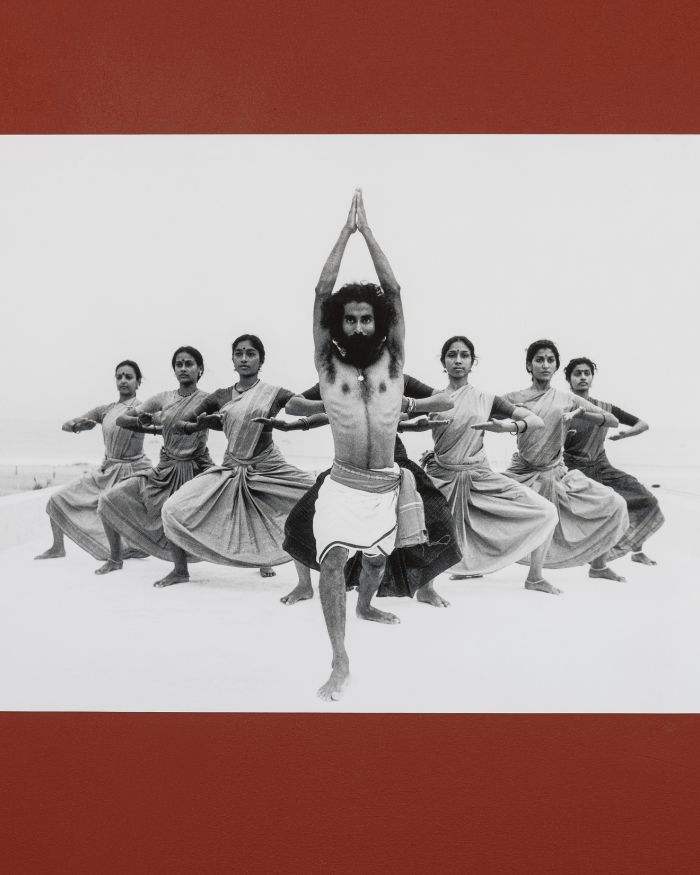

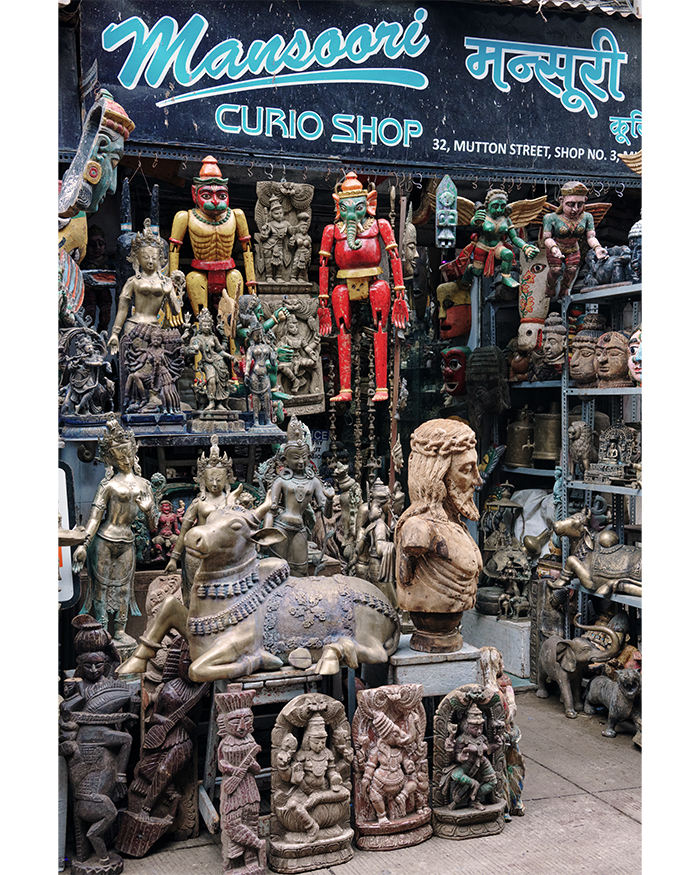

We arrived at the title to carry as an active gesture. It pursues doing rather than postulating, and yet remains open to a propositional mode. We are reflecting on forms of inheritance, lineage and marking presence — the knowledge, values and practices held within creative individuals and communities and a collective need to shed the tyrannical rules of broken systems. How do we reconcile the inequities of this moment? While holding space for both tenderness and rage, how may we continue to correspond with deep pasts and rhythms of futurity? to carry approaches biennial-making as a collective wayfinding. Amid tides of annihilation, it is a modality of sense-making and insistent looking back, inwards and across, instead of turning away.

Decades ago, James Baldwin reflected, “I’m terrified at the moral apathy, the death of the heart, which is happening in my country. These people have deluded themselves for so long that they really don’t think I’m human.” The artistic processes, performances and sonic offerings across venues convene forms of remembrance, Indigenous knowledges and communal learning, the radiance of love, caregiving and mourning, the braiding of kinship and lament as swelling currents mobilising against the atomisation of self and world.

How did the collective curating process unfold for this edition?

I’ve been working in collective formations for biennial-making for some time now, so there is a familiarity with pathways to conceive and materialise large exhibitions in a group. We each had autonomy over the artists we wished to engage with and led on specific projects. As we had never worked together before and some of us were even meeting for the first time in person it was crucial to have time to develop a common vision, while also maintaining the freedom to compose chapters within it that differ in methodology. Each of us identifies as cultural organisers in different geographies, committed to institution-building, generating public discourse and community-led perspectives.

"As curators, we don’t distinguish between artists who have worked for decades and those at the beginning of their careers" — Natasha Ginwala