Portraits in the banner image by Madhavan Palanisamy

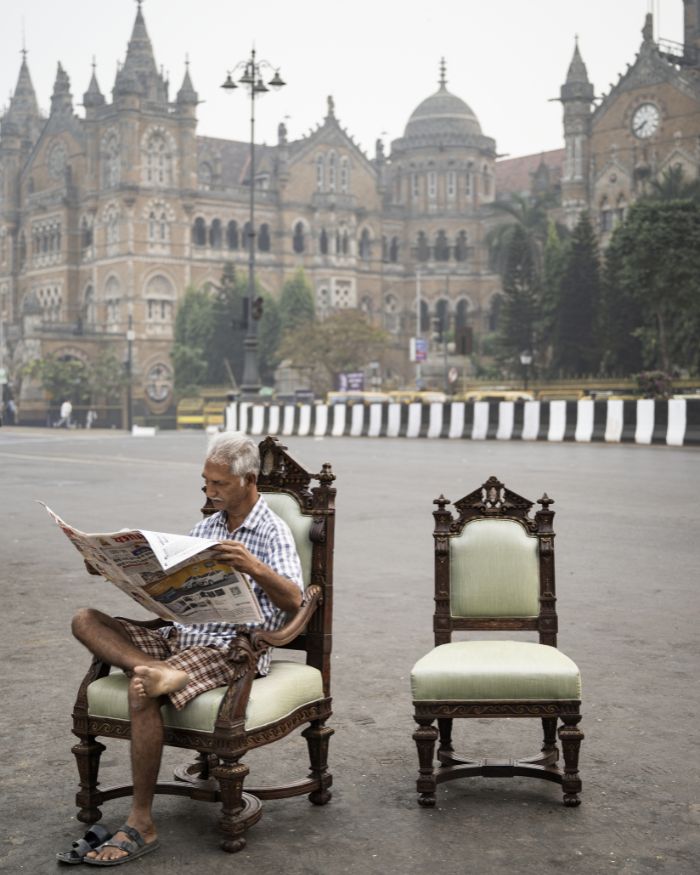

In the Deccan, surfaces are rarely still. From temple towns to mercantile streets, a single decorative instinct runs through the region: an inclination towards density, layering and naturalistic detail. Granite is carved into tiers of deities and dancers. Timber and tile crowd the facades of trading houses. Cloth is adorned with medallions, flowers and animals. Behind these crowded surfaces lies a long history of movement and contest. Trade routes brought bullion, dyes, silks and new motifs into port cities and inland courts. Armies and invasions redrew boundaries, prompting rulers to build in stone as a statement of protection and power. Mercantile communities channelled profits from distant colonies into ancestral homes, converting credit and risk into marble floors, carved ceilings and saturated walls. Court workshops translated the same anxieties and ambitions into textiles embroidered in silk and metal thread, turning portable cloth into archives of status and alliance, alongside myths and belief systems.

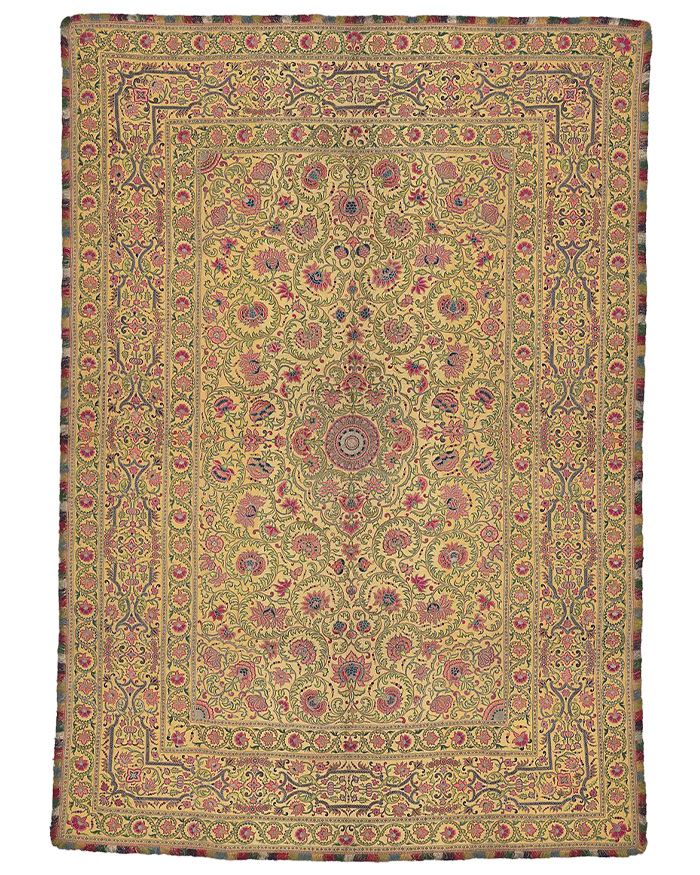

It is within this larger web of exchange, conflict and patronage that one particular lineage of embroidery was stitched into being. As founders of a Chennai-based embroidery atelier, whose artisans have lived in the surrounding villages and practised their craft as a continuous tradition for more than 400 years, we have often asked ourselves about their heritage. With no written records on the subject from that time, our chance encounter with embroidered textiles categorised as Medallion embroideries from museum collections, in telling the story of their provenance, unveiled some of the mystery. And would place our craftsmen as descendants of artisans of the kharkanas of the Deccan courts. One of the most outstanding examples from the Victoria and Albert Museum is said to have belonged to Tipu Sultan. It is a densely embroidered cloth featuring a central medallion from which four flowering trees are spread, each corner bearing a quarter medallion, framed by a floral border with cavorting animals, itself flanked by narrow guard borders.