Produced by Shriti Das

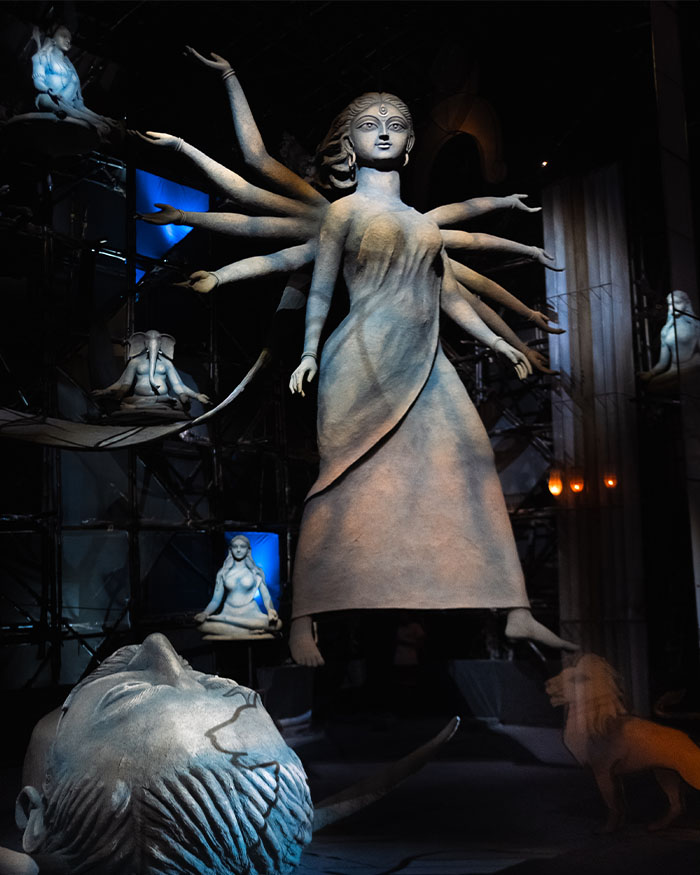

What can I write about Calcutta’s Durga Pujo that has not been written before? Perhaps nothing. Maybe that’s the point. Some stories never tire of being told. I have no new perspectives to offer. But across two days, I would reclaim a culture that was always mine. Because you can take the Bengali out of Bengal, but you can never take Bengal out of the Bengali.

CAN YOU EVER ESCAPE CALCUTTA?

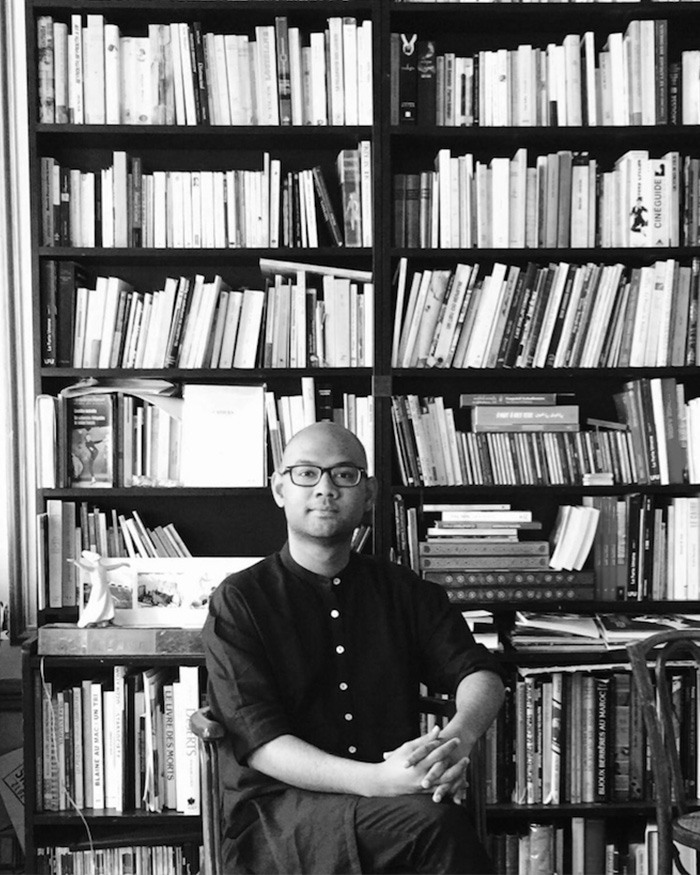

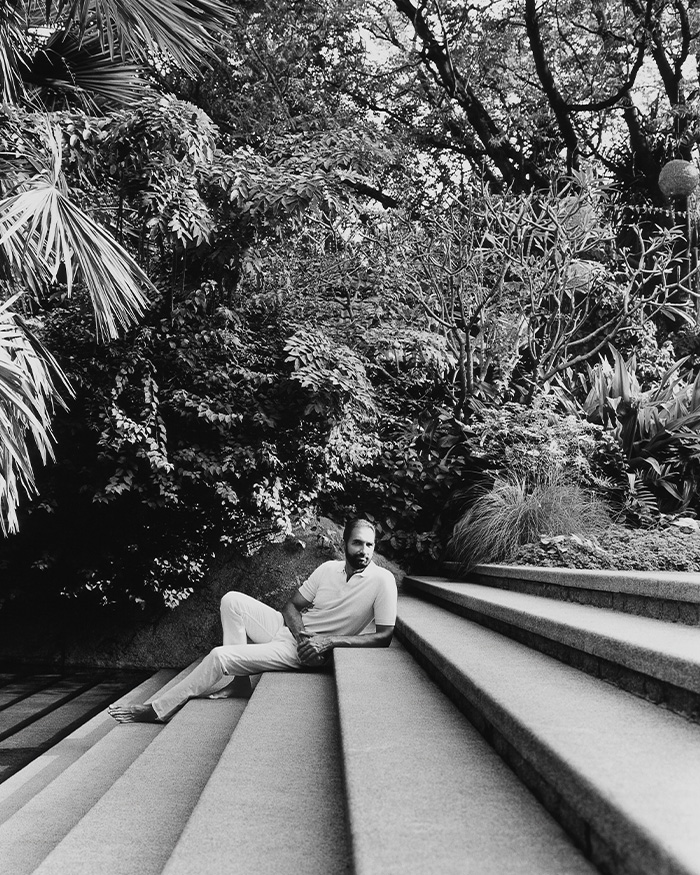

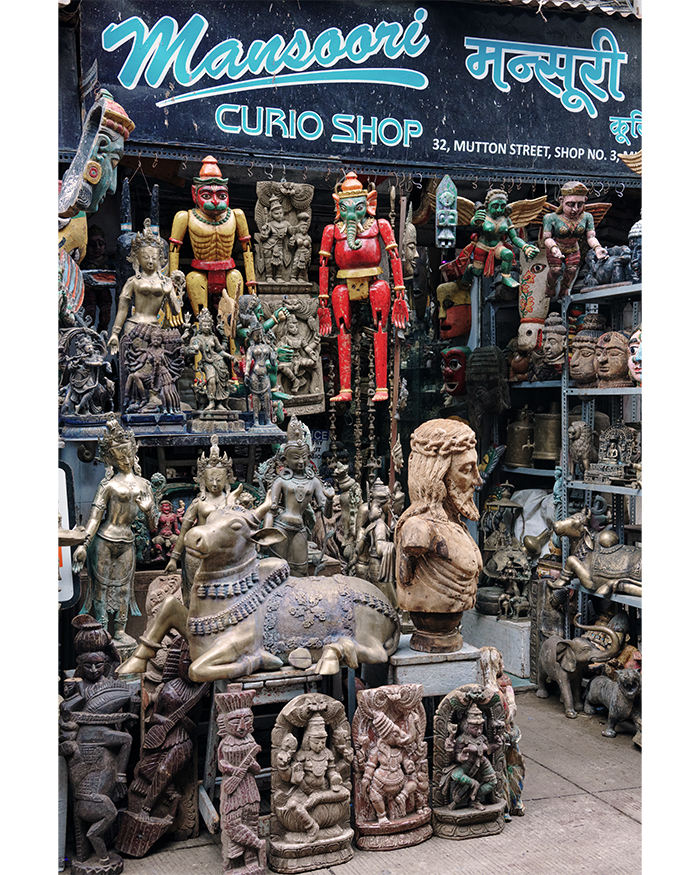

I had always consciously distanced myself from Calcutta. I would roll my eyes when people assumed I was from Calcutta. Simply because I’m (half) Bengali. “Bengal has more cities than Calcutta,” I’d snark, in that quintessential Bengali way of getting annoyed at ignorance. The other half of my lineage is Oriya, and the Bengali side of me has zero familial ties to Calcutta. Yet Calcutta insists on inserting itself into lives. There is a reason why this city stays alive in the hearts of even non-Bengalis native to it. Take for instance, Ajay Arya, the Marwari designer from Calcutta who extended this invitation to visit the City of Joy to see the UNESCO-recognised pandals during this year’s Pujo. Ajay’s father Vijay Kumar Arya even started a pujo in Bengaluru in 1980 called Kalasipalyam. Marwaris, Punjabis, Gujaratis, and even the Chinese and Armenians have long woven themselves into Calcutta’s fabric, shaping it as much as belonging to it. In their own way, they show how the city belongs to many, perhaps, in time, even me.

"This year, for me, Pujo began early as I stole these few days before Mahalaya. Not the clang of dhaak or the unveiling of Maa’s eyes on shoshthi but within the near-complete pandals, in scaffolds and stories"