Women in design, women artists, women’s magazines. Growing up around a feminist mother and later being taught by feminist professors, I wasn’t prepared for the unease among peers when I mentioned the publication I’d be writing for. It was the divisive name — ELLE DECOR. At first, I assumed it was “elle”, translating to a “she” in French, an idea that often risks wounding fragile masculinity. But it was the latter half — DECORATION — that sparked their reaction. We were feminist enough to accept femininity but had we dismissed decoration too quickly?

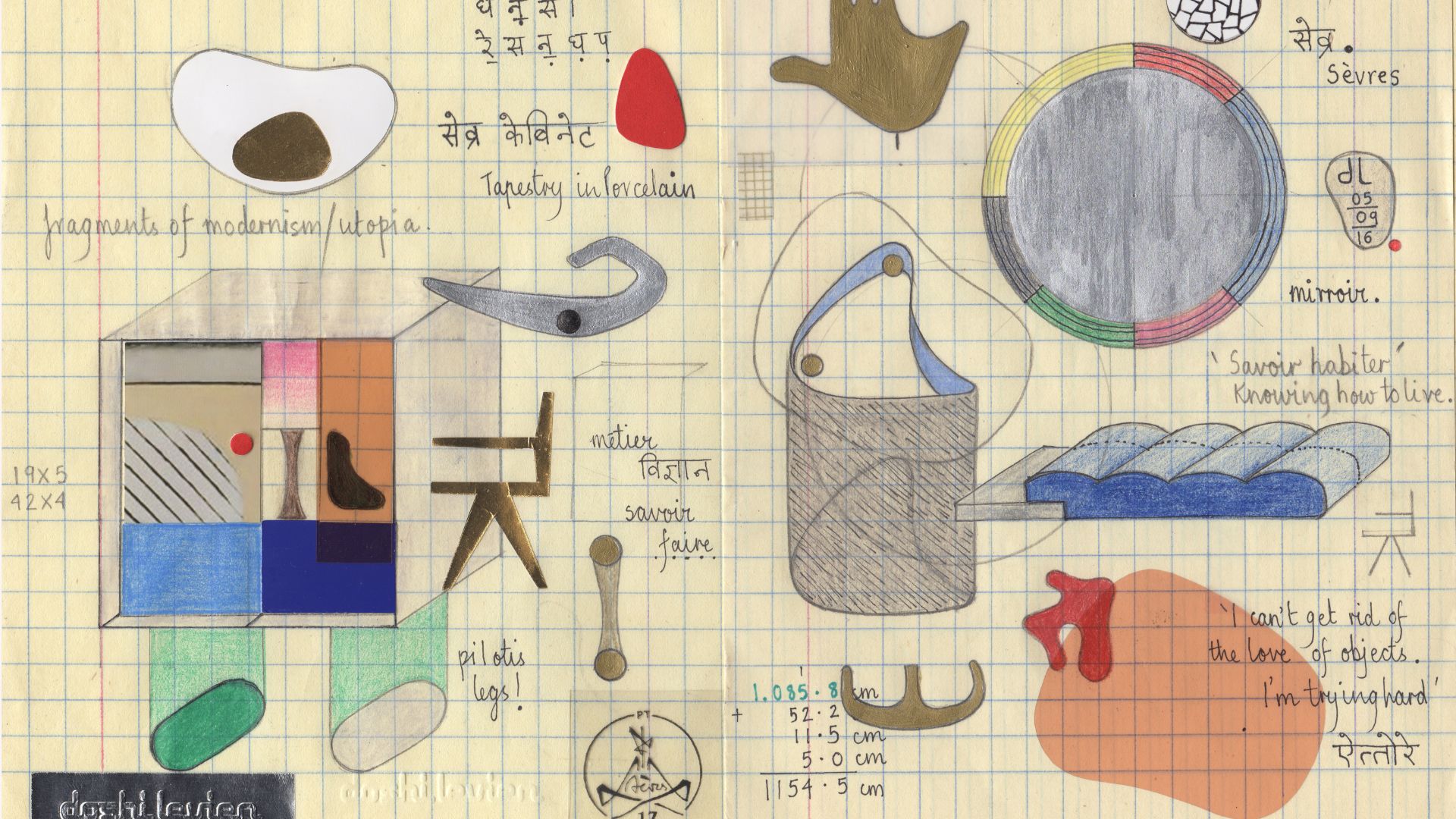

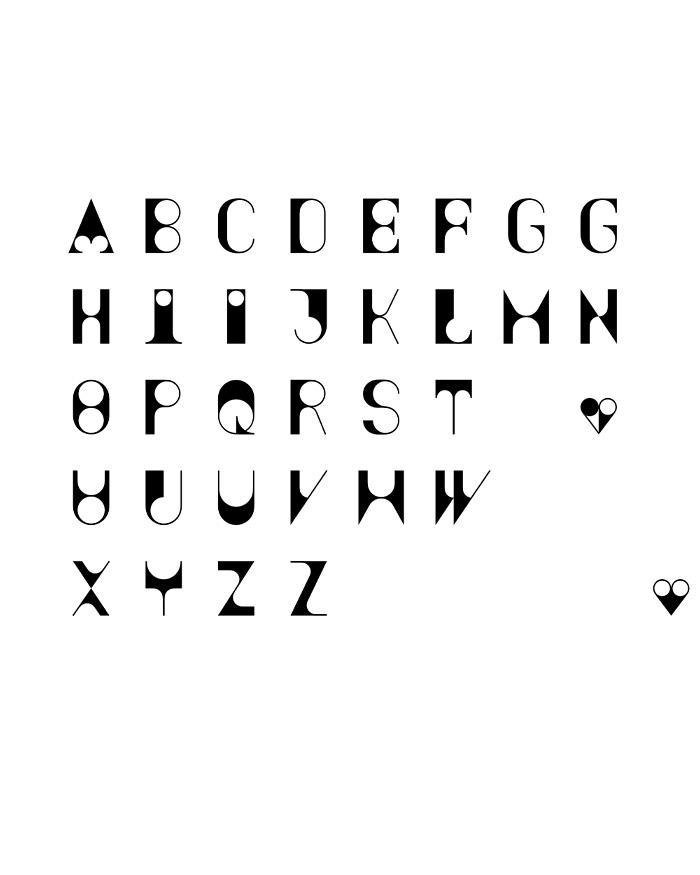

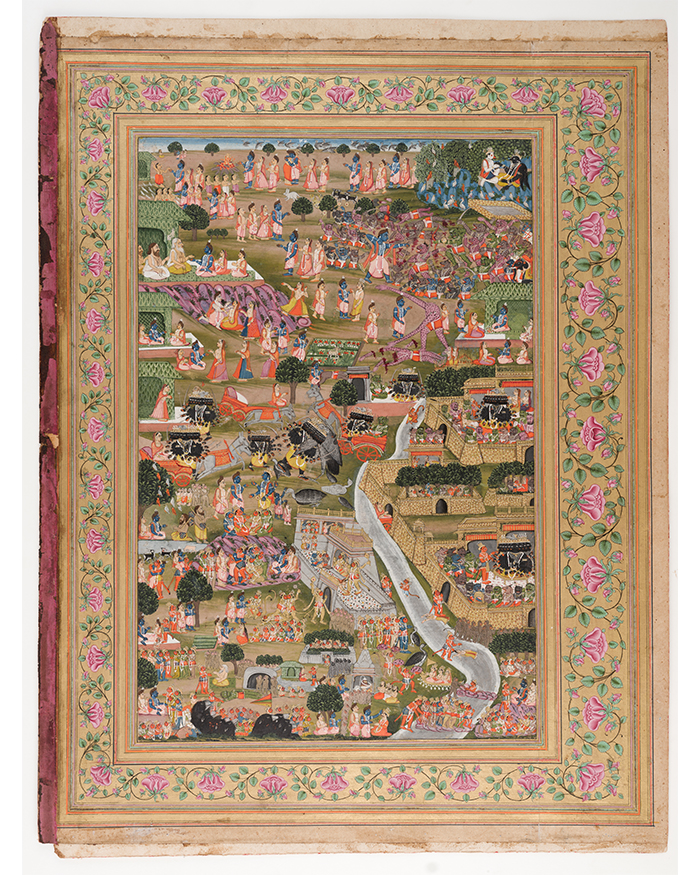

Walking through old Mumbai with Nipa Doshi, I began to see decoration, femininity and feminism in a new light. Her perspective challenged not just the narratives around decoration but also its interplay with colour, gender and history — a lens through which the city’s layers of identity came alive. The arches of Mumbai Samachar stood out with charismatic flamboyance, a dilapidated bus stop became a work of art and the arcades of Horniman Circle turned into grounds for imagination. Surprisingly, ornament was omnipresent — in the bearded keystones, in the brilliant red bricks, in cursive typography. Nipa finds beauty and meaning in this environment, “It is a place where history, commerce and daily life come together.” Beauty to her, does not just materialise from what we see but also through its contextual narratives and how we appropriate urbanity over time. Then was decoration not gendered but a human desire? Perhaps, we only make beautiful what we cherish, what belongs to us.