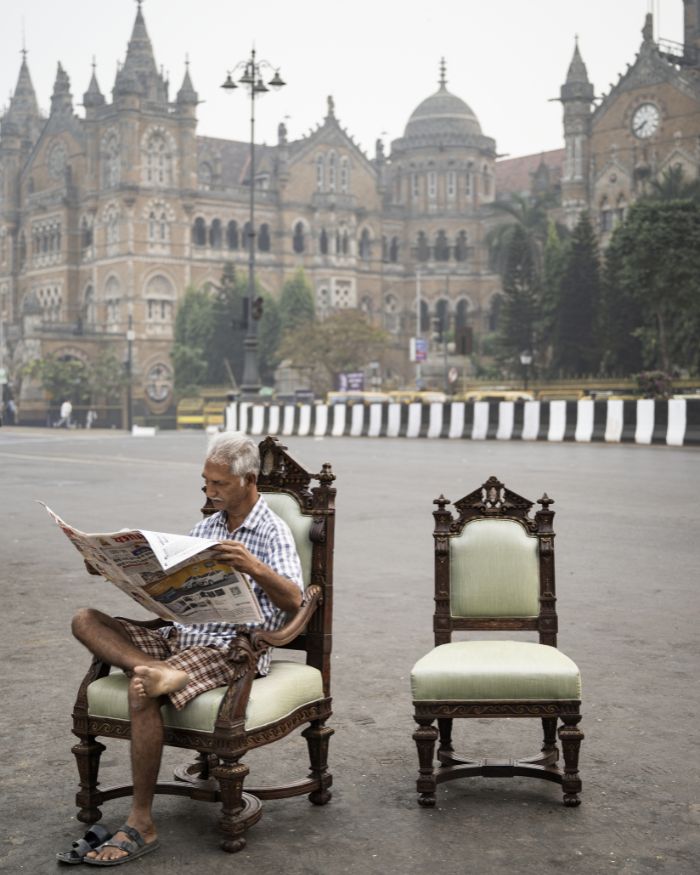

Hindustan ek khwab hai. India is a dream. In 2019, when the country was engulfed in protests that questioned who gets to call themselves Indian, these words by poet and artist Aamir Aziz became a rallying cry of dissent. Dreams are a tempting provocation. Empires fall, governments change seats and still we harbour our desires despite all odds — for dreams have no proprietors, no moral obligations, nor any inkling of bounds. While some dream of palaces, others still aspire for a life with basic dignity. Yet even in this Tower of Babel, there is common ground. A dream of a better future. It appears in how everyday life presses back and how we repurpose spaces designed to exclude. The lynchpin of the world’s largest democracy may lie not in erasing the darkness of our shared past, but in noticing how daily life recasts it into a cacophonous, lived present. A maximalism of the spirit.

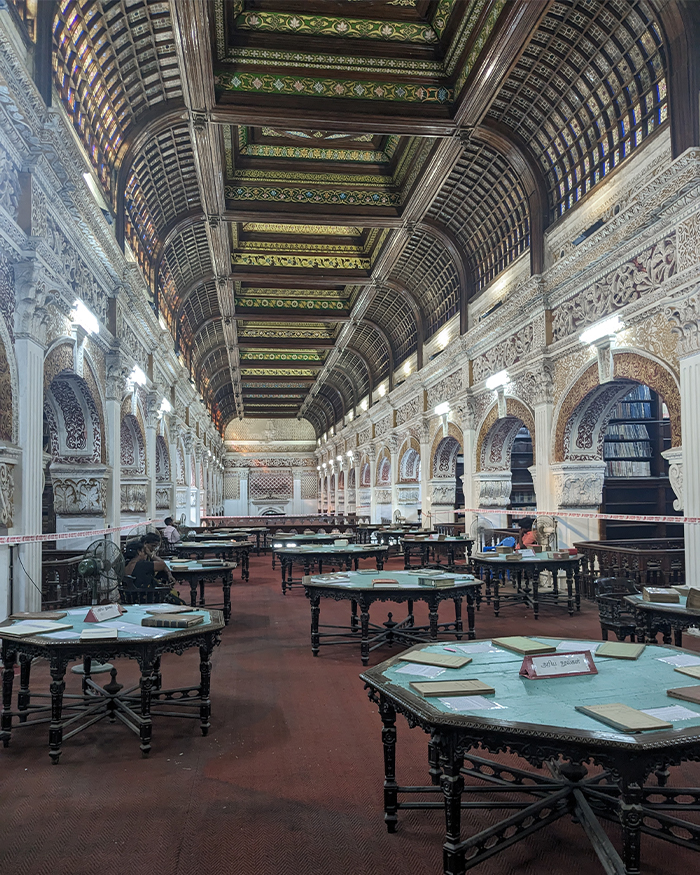

In 1857, by the Arabian Sea, a centuries-old port city trading with Persians and Arabs was on a quest to become Bombay. Urbs Prima Indis required a stage to display the greatness of Britain’s crown jewel colony. This ambition produced the Government Central Museum, later renamed the Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum after the city’s first Indian Sheriff. When Tasneem Zakaria Mehta encountered it in 1994, the building stood derelict, dismissed as a colonial relic. “I was determined to restore it,” she recalls, “but no one understood the importance of conservation at the time.”

“While each object’s story highlights the city’s remarkable character, embedded in them is also the history of colonisation and that history is equally important to deconstruct”

— Tasneem Zakaria Mehta