In architecture school, my professors introduced me to Freedom Park as an initiation into what architecture was meant to be. As I moved through the barracks and the panopticon tower of the former colonial-era Central Jail, what I was meant to grasp was unmistakable, even as a student — a reimagined appropriation of an exclusionary surveillance typology. Five years later, as I speak with Nisha Mathew and Soumitro Ghosh of Mathew and Ghosh Architects, much has changed in Bengaluru. Freedom Park has now become the city’s only “designated” space for dissent and protest. Soumitro reflects on the project’s origins: “The liberation of the jail into an urban park was announced through a competition. It marked a unique moment in post-dot-com boom Bengaluru, reflecting the city’s people, history, heritage and aspirations.” Through architectural intervention, a site once considered outside the city and out of bounds was transformed into one open to all. “Democracy must be negotiated and engaged with,” Nisha adds. “And the role of an architect is crucial in enabling those engagements.”

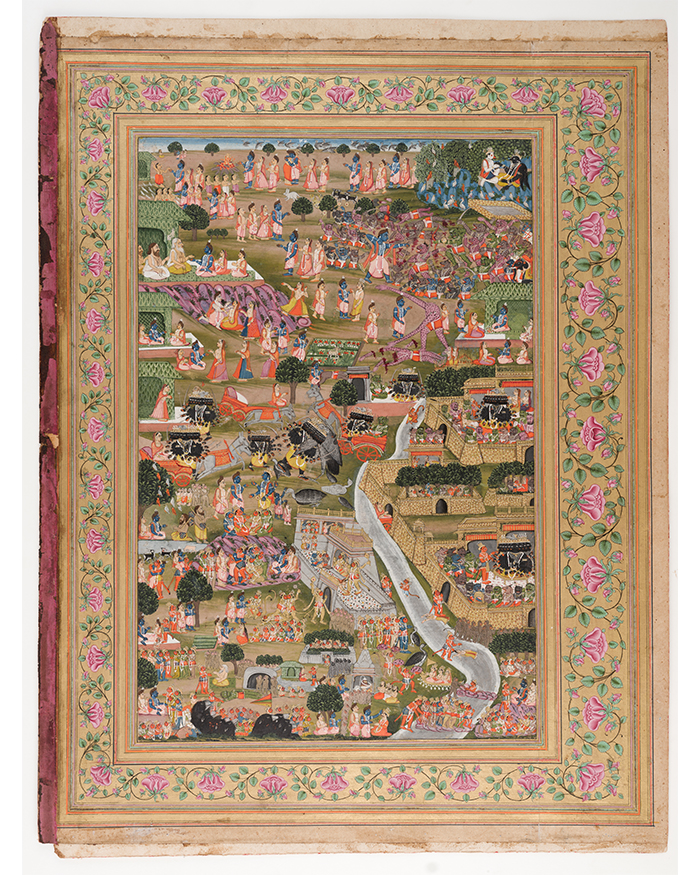

"I've always wondered why monarchies produced better public spaces, and why in a democracy (By the people and for the people) architecture suffers more than it ever did"

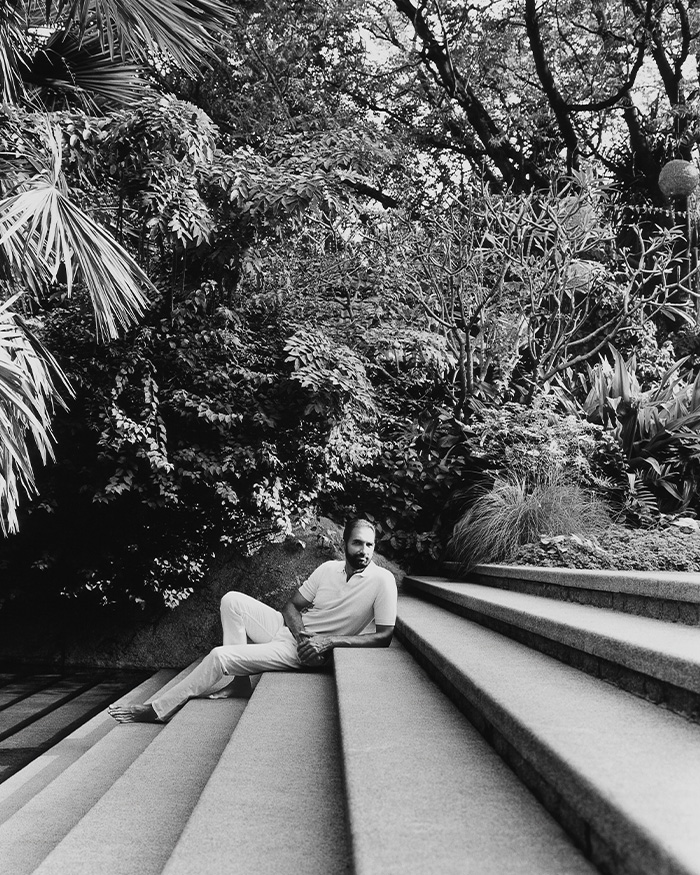

Soumitro Ghosh of Mathew and Ghosh Architects