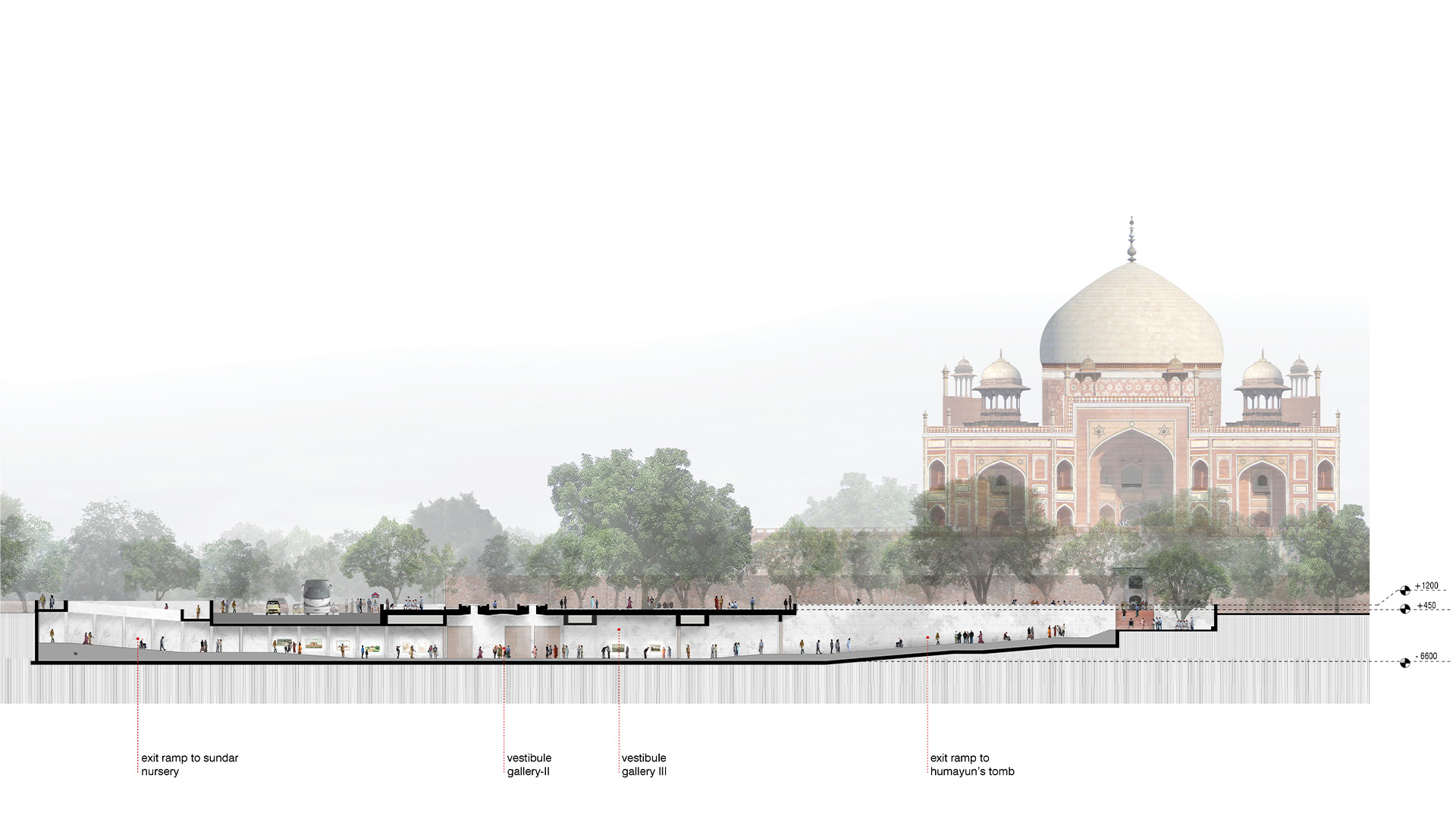

I first saw the section drawing of the Humayun’s Tomb Site Museum in architecture school. It was projected onto a screen, a crisp slice through the earth. A subterranean world held together by light. We analysed it the way students do: tracing the lines, measuring the proportions, admiring the clarity of the design. But, like all theoretical encounters, it remained just that. An abstraction. Now, the idea comes alive in solids and voids.

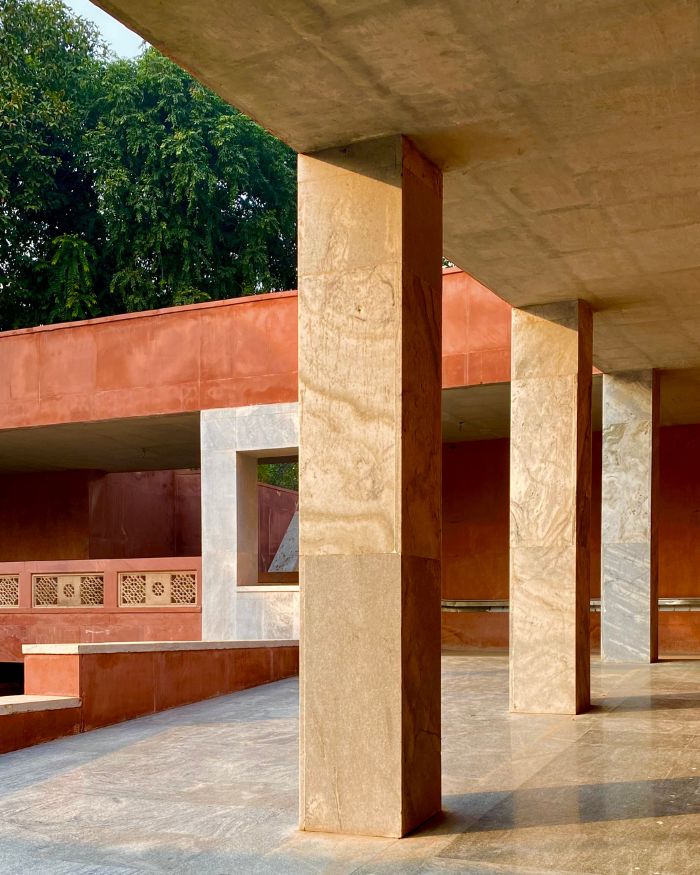

For most of us who grew up visiting Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi, the experience was always the same — arrive, marvel, leave. “There was no reason to be in the vicinity of the building once you had seen it,” says Pankaj Vir Gupta, the museum’s principal architect, who with his partner Christine Mueller, leads Vir.Mueller Architects. The tomb was a moment of beauty, but never a place to stay. This museum, commissioned by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture changes that.

“The minute you sever the links with beauty, with the capacity for architecture to impart joy, you undermine the entire architectural identity” – Pankaj Vir Gupta