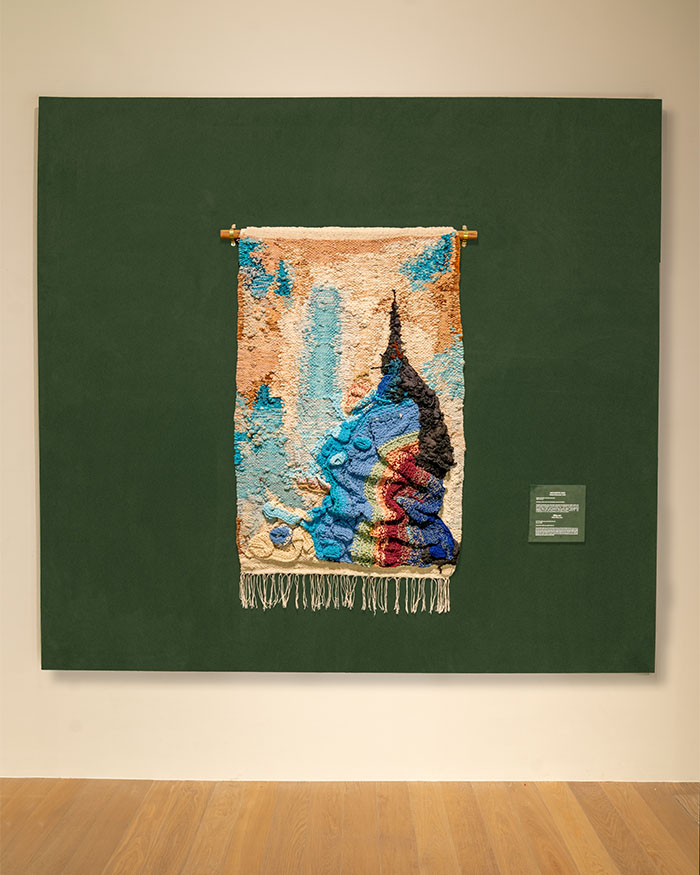

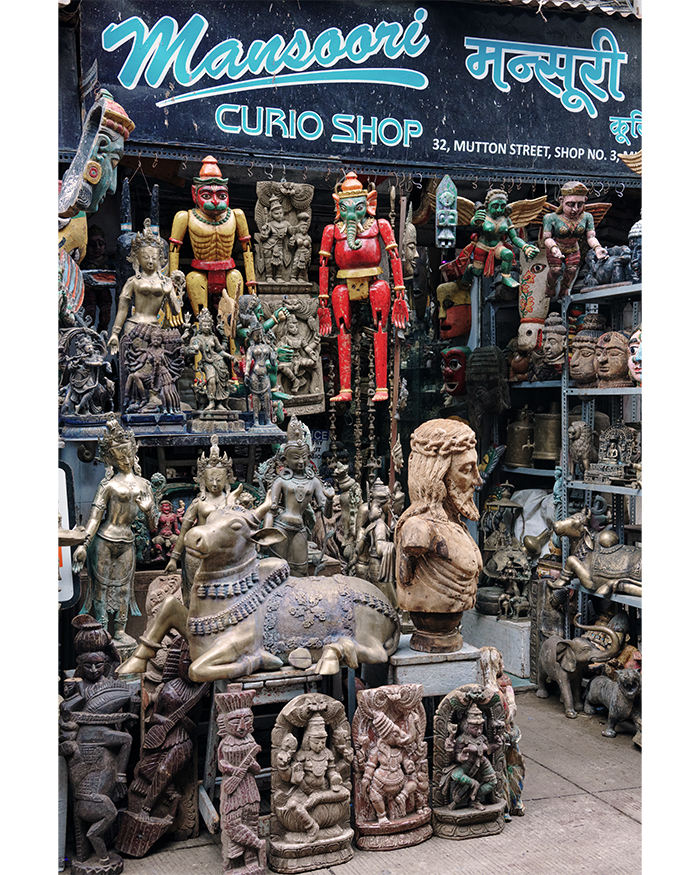

Call it a collective revulsion of the arcane and uncanny. Why do we fear what we cannot control, and when does that fear morph into awe? As I stand in the Art House of the Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Centre (NMACC) Mumbai, surrounded by Bvlgari’s bejewelled ornaments and curated objects of art drawn from life, the motif of the serpent recurs throughout.

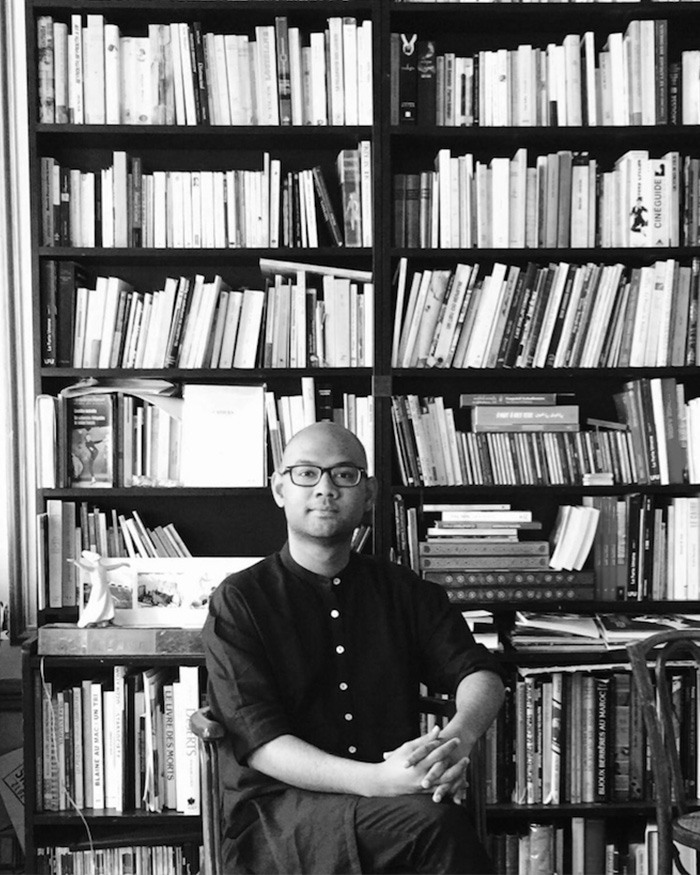

In cultures across the world, snakes are seen as duplicitous creatures, associated with trickery and treachery. Sean Anderson, the artistic director of Nature Morte and the mind behind the exhibition, describes the Nāga as a universal symbol. “If we remove the physicality of it, and just think about it as a metaphor, it’s about self-reflection and shape-shifting. I can peel off my skin and become a new being. It is an image that goes from one context to another. It’s visible. It’s invisible. It is in itself a world,” he tells us.

“By placing indigenous and contemporary artists in the same space, I’m also saying that the so-called art world has long diminished one group of practitioners in order to create value for another sect”

Sean Anderson of Nature Morte