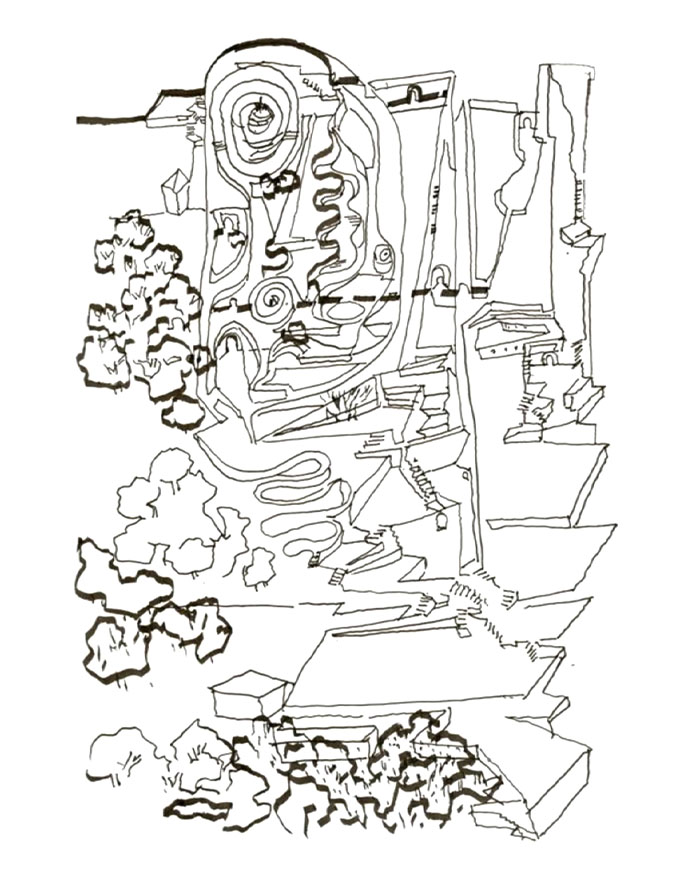

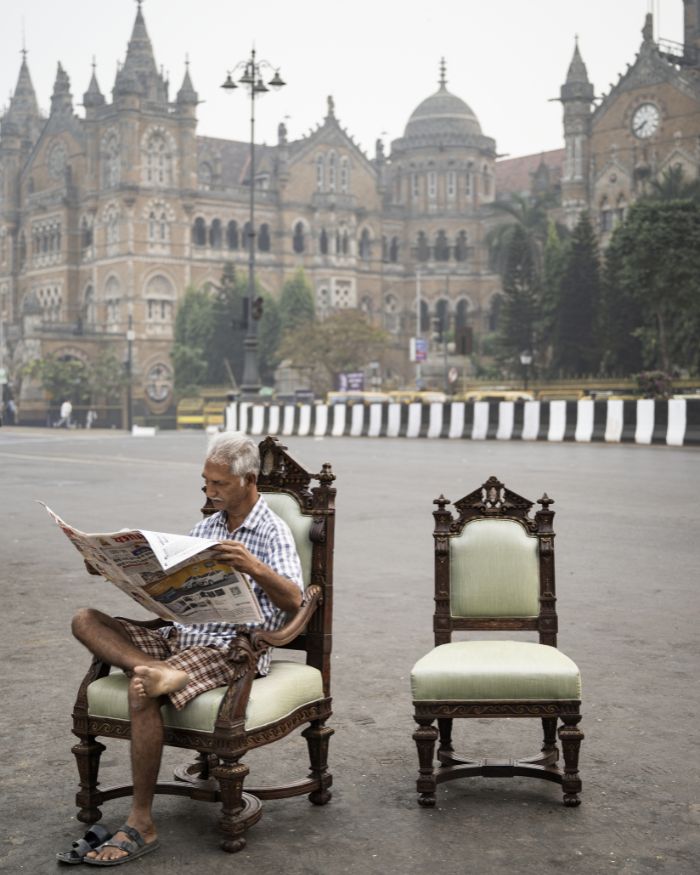

All eyes are on Vitra. Yet what is perhaps the most anticipated structure in the world remains perplexingly silent. Therein lies its provocation. Patina-covered walls emerge from the lush terrain, warping, folding and curving into themselves. Within, an almost unbelievable quiet prevails, interrupted only by the treble of a gong, its resonance drifting through the ether and evoking the uncertain intangibility of spirit. The Doshi Retreat stands apart from its predecessors on the storied campus in Germany, distinct both in form and conception. Designed by Khushnu Panthaki Hoof and Sönke Hoof in collaboration with the much-revered Pritzker laureate Dr B.V. Doshi, this space for contemplation invites multiple readings, some provoked by its physical gestures, others more subliminal, discernible only through their spatial and temporal conditions. Each architectural form on the Vitra Campus functions as both a barometer of the zeitgeist and a projection toward the future. Situated among the greats: Zaha Hadid, who tested the limits of form; Frank Gehry, who questioned the validity of meaning through Derridean Deconstructivism; and Buckminster Fuller, who probed the geometry of the atoms that constitute the human body, the Retreat instead turns inward, beyond materiality and toward the metaphysical. Rolf Fehlbaum, furniture designer and former chairperson of Vitra, elucidates why, “The world has shifted. Confrontation, polarisation, war and authoritarianism have become increasingly prevalent.” For him, a space reflecting Doshi’s values is more crucial than ever. Rolf continues, “He built bridges between East and West, between science and spirituality, tradition and modernity, and his world was one of humility, generosity, humour and reconciliation. Values that are very, very much needed today.” In a series of reflections, Khushnu and Sönke, who lead Studio SANGATH in Ahmedabad, unravel the making of an architecture that speaks to our time, in the pursuit of presence itself.

Could you walk us through the process of collaborating with Doshi on the Retreat, from the first idea to the realisation?

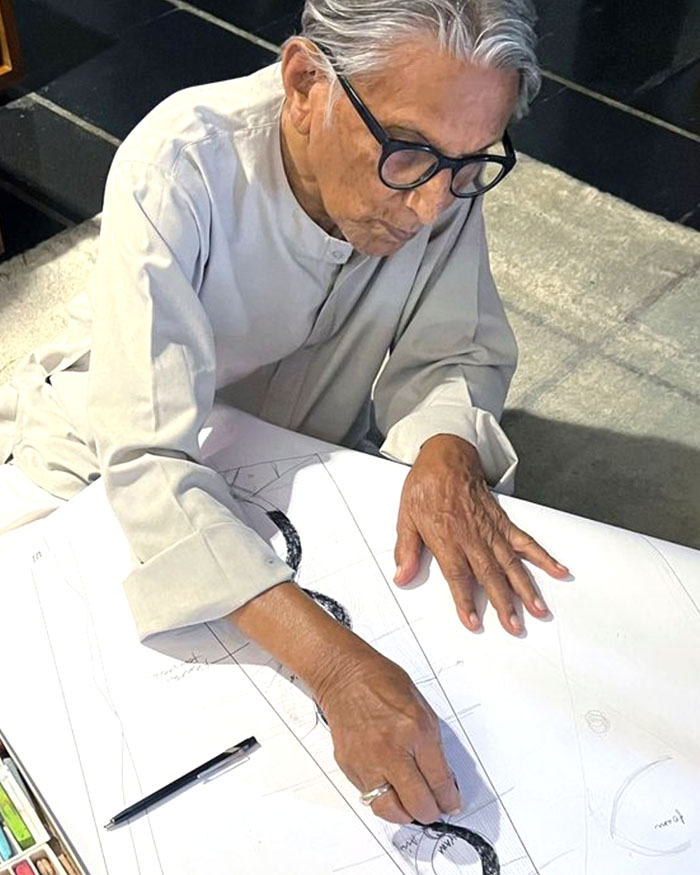

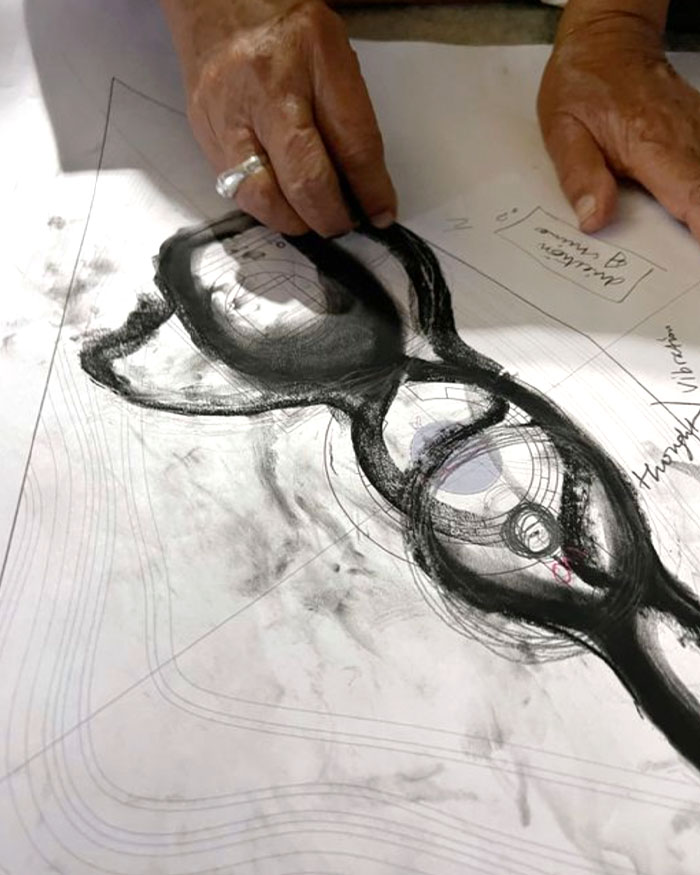

It all began with a conversation about what we wanted people to feel. That led to all three of us describing places where we had experienced a sense of calm. From there, our dialogue evolved, and we agreed that the journey itself is crucial to arriving at a place of stillness and presence. We developed several models in clay and foam, experimenting with different ways of creating that journey. One thing we knew for certain was that it could not be linear but rather a subtle choreography of movement and slight disorientation, so that even momentarily one might lose oneself and become truly present. A few months later, we presented five iterations of what the Retreat’s journey could be to Doshi. Among them was an intertwined path where one gradually descends into the ground and then re-emerges. When Doshi saw this model, it reminded him of a dream from his childhood, of two intertwined cobras in his ancestral home. We took that as a sign, almost intuitively, to develop it further. The project began with shared curiosity, intuition and presence rather than blueprints. This recollection of his dream became our anchor, a metaphorical and physical framework. The process was tactile and guided by modelling and experimentation. From there, we translated the idea of the intertwined path into concrete spatial decisions: the slope and curvature of the path, its length and width, its depth, the rounded edges to create a sense of embrace, the lowest point to heighten intimacy, and the proportions of the gong chamber to balance sound and scale, all attuned to human presence.