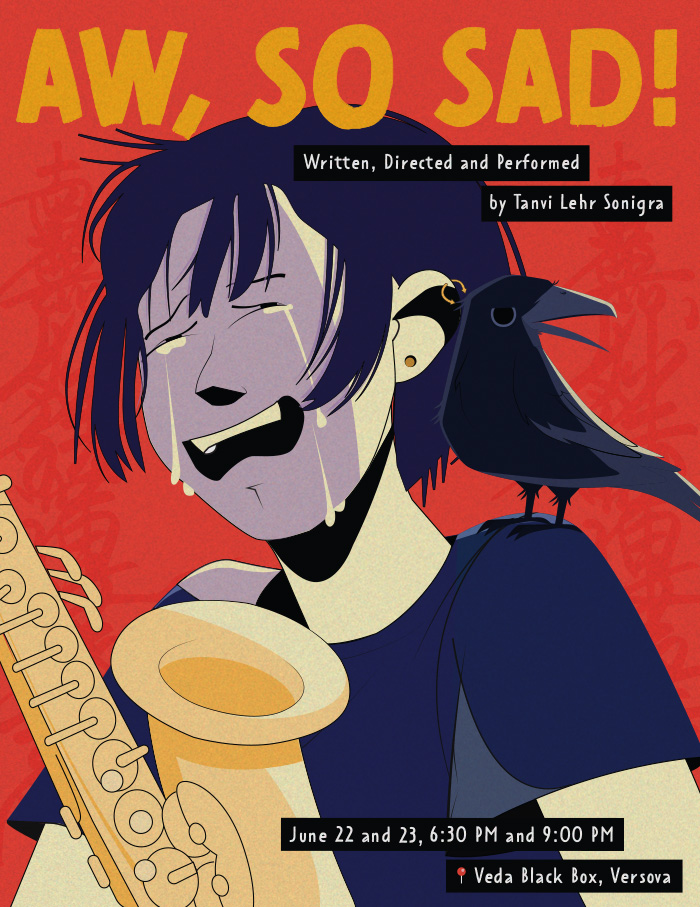

“Mumbai apartments are so small, so cluttered, there is no space to do anything!” Tanvi Lehr Sonigra exclaims in exasperation. On a Saturday night, abandoning my chock-a-block to-do list of laundry and doom-scrolling, I left my own small, cluttered Mumbai apartment to watch her perform Aw, So Sad! — a play by Ek Tappi Productions that is written and directed by Tanvi.

Meet the protagonist, a 20-something-year-old saxophonist Sad Woman who shifts the scene from her one-room kitchen apartment to her dreaded workplace, the Senorita beauty parlour to the studio apartments of silver-tongued violators, all with a soundscape of chants, incessant notifications and monologues.

There might still have been enough room to go about her life in all of these small spaces had it not been for the insurmountable weight of unfair gendered experiences. Perhaps, “space” is more than four walls?

As someone who lives alone in a similar bed-sit situation with comparable existentialism haunting my (lack of) hallways, the conversation with Tanvi about the process behind her performance was a provocation I was not prepared for. Dark and satirical, the 80-minute play is not for the faint of heart and Tanvi doesn’t shy away from the uncomfortable.

What does home mean to you?

It’s a longing for a space I have only experienced briefly. It’s a space filled with love, safety, art, music, wholesome lunches with my loved ones, and camaraderie. It’s a space where I can do nothing, be unapologetic, and breathe. Trust me, sadly, it’s a luxury for many.

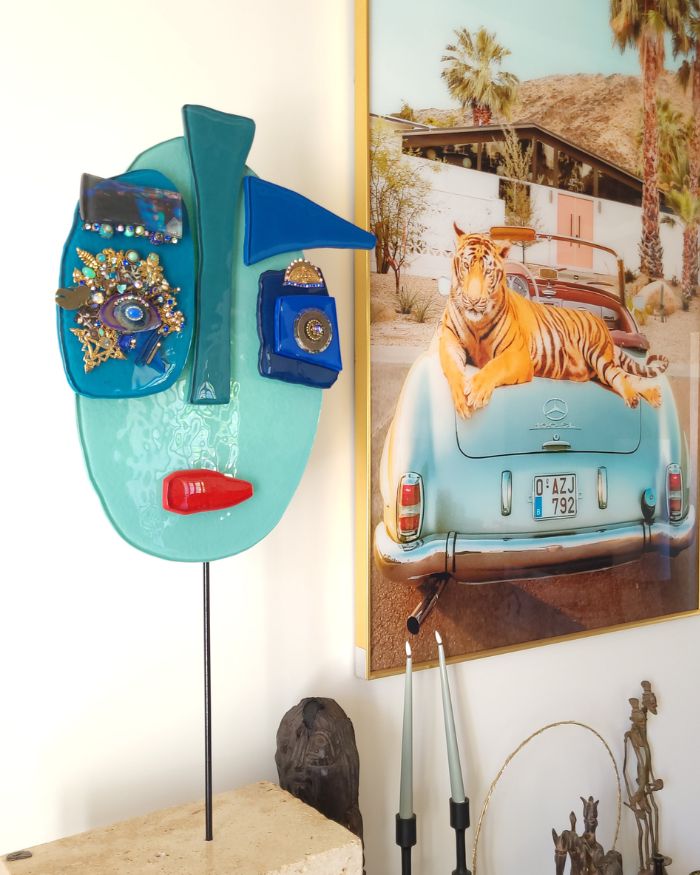

Could you walk us through the design of the set and how different elements come together?

Deviser and set designer Mati Rajput hit the nail when she brought in very achievable ideas for the protagonist’s psyche to reflect in the set. As envisioned by Mati, the protagonist, Sad Woman is learning how to draw boundaries and you’ll notice that all set pieces are outlined.

We wanted to make it look straight out of a comic book (with larger-than-life set pieces) as the character uses humour to deflect from her own pain. She realises that although everything around her seems unreal (or comical), she is real. There is a long way for us to work on it, but we have taken a step to begin looking at how architecture affects moments of upheaval.

How does the physical space of the apartment become a character in the story?

The clutteredness of the apartment is reflective of her mind which is the consequence of the clutteredness and confusion that ends up happening in abuse, which is difficult to break.

Can you walk us through the process of writing, directing and performing this play?

There were a few central questions I was working with: When it comes to abuse, who do you choose to believe and why? What’s your threshold for violation and how much does one allow? When does your politics as you claim to be personal actually become personal? What does justice look like?

As for directing, I had a vision of how I saw it unfolding on stage and that dictated the writing as well. I wanted to tease the audience with my performance, hurt them when they least expected it and also ease them when they most needed it. Physical theatre and clowning were the forms I wanted to incorporate into the life of the characters and Mati Rajput pushed me to achieve it.

I also wanted to work with a solid soundscape as the protagonist is a saxophonist and wanted the audience to see the story unfold through her lens (or should I say ears.) Romy Italia, the sound designer and operator, is a co-performer even though you never see him on stage. Our timing is everything. Jayesh Malani, the saxophonist and Prajesh Kashyap, the singer bring such magic and suave to the music, Kartik Sharma and Simrat Harvind Kaur bring levity and gravitas to their characters. Payal Kalra and Suraj Subramaniam elevated the piece with lights and animations.

Could you expand on the term, “the personal is political”?

Politics begins at home. So for me, it’s about being able to freely talk and share about what’s going on at home just as I talk about what’s going on out there. It’s also a constant reminder to myself – does what I say align with what I do? It’s a good start for us to keep in check and then also be open to our viewpoints evolving with time.

For most queer folx, our bodies often become subjects of debates. How do you negotiate lived experiences and the body as a medium of storytelling?

I don’t negotiate anymore. Inherent within the story is the body and lived experiences, regardless of being queer or not. I focus on crafting the performance, training my body and living up to a standard I have set for myself.

You must be wondering why you are reading a story on queer experiences after Pride Month has ended. After all, the rainbows are losing colour from corporate logos and the siren song of straight allyship is also about to fade. A month full of frills and nothing to show for it. Or is it? Here is what the artist behind the Sad Woman thinks. “Pride for me is non-existent until it is existent for everyone. Pride month in my brain doesn’t exist because all I want is pride all year long.”

You might also like: What makes a metropolis? Parallel Cities at Nature Morte’s Mumbai gallery searches for answers in the urban experience