People

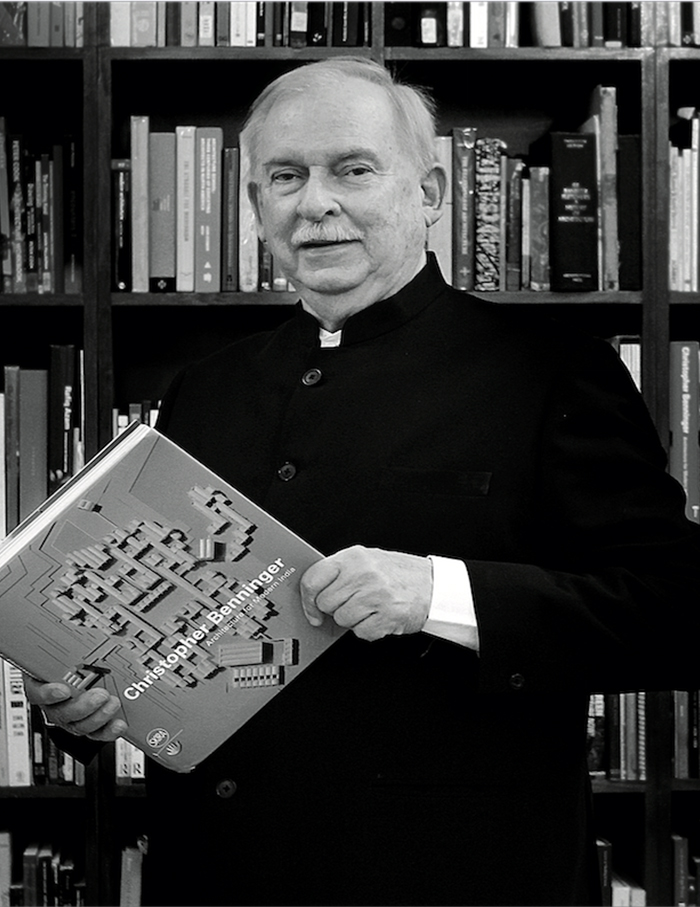

Pune-based architect Christopher Charles Benninger’s design journey is a marvellous inspiration

AUG 14, 2019 | By Anamika Butalia

It all began with a Christmas gift he received as a young lad. Wandering in a complex world in search of meaning and a sense of identity, receiving Frank Lloyd Wright’s The Natural House from an aunt changed everything. “I’d never read a book cover to cover before,” says Christopher Charles Benninger, “When I finished reading the entire tome at 4am, I walked out of my house, looked up at the star-studded winter sky and said to myself—‘I am an architect.’” The American then went on to realise his dreams.

He studied urban planning at Massachusetts Institute of Technology on a Carnegie-Mellon Fellowship, and completed an architecture degree from Harvard Graduate School of Design, where he eventually took up a teaching job in 1969.Circa his late 20s, he’d been promoted to an Assistant Professor at Harvard, which, as he puts it, “amounted to a tenured appointment where I could have still been today”. But, on the heels of a previous trip to India in 1968 to design houses for Vadodara’s slum dwellers, during which he’d interacted with the illustrious Balkrishna Doshi, he got a call that affected the course of his career. Benninger remembers Doshi’s advice, “He said: ‘You will be 28 only once in your life, and you will only have one chance to found a school of planning, more or less single-handedly. This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to make a contribution to mankind.’” So, Benninger packed his bags, moved to India, and founded what is now called the Faculty of Planning at the CEPT University in Ahmedabad, where he still sits on the board.

His works have covered the entire gamut—residential, commercial, institutional, hospitality and urban planning. His key influencers were his numerous teachers. “Collectively, they merged into an image of what I wanted to become in my life,” shares the ever eloquent creative. So, inspired by one of his gurus, he stuck to planning and writing urban policy papers for several decades.

One day, in 1993, at the Centre for Development Studies and Activities, which he founded in Pune in 1976, a group of 40 architectural students came to sketch his designs and asked him to pose in a photograph with them. Urban plans and policy proposals didn’t get him this kind of appreciation, recalls Benninger. By the time they’d said ‘cheese’, he had decided to return to architecture.

When asked about what he considers the most important criteria for design, he elucidates, “First comes the client’s brief, which defines the functions, purposes, emotive requirements, budgets and schedules. Then, the site and its social, environmental and geographical context are factored in. This is followed by what I call the ‘Culture of Construction’, where, as an architect, I take an informed decision on the materials, local skills, available technologies and resources to be employed to bring in a sense of context and relevance to a project. The next two steps involve the questions ‘What can I contribute to this place and to those who will live here that no one else can?’ and ‘Whether to fit the design into an existing urban context or break away from negative patterns and seek new beginnings?’”

Two of his most unique plans are the Sites and Services mass housing project and the Self Help Housing plan. The former was based on his Harvard thesis, which he’d designed for the city of Medellin in Colombia. “While my classmates were showing off large, concrete and glass multistoreyed structures, I conceptualised a participatory process,” says Benninger, who was asked by the World Bank seven years later to turn the theory into a real No Cost Housing solution. Meanwhile, the latter is the result of his exposure to Ekistics— the science of human settlements. “I realised those principles for a programme accommodating 15,000 families in Chennai in 1973. It led to the emergence of my ideals of intelligent urbanism,” he adds.

Benninger goes on to share that 50 years ago, after seeing Kirtee Shah’s design of affordable housing in Ahmedabad called Vasna, he began to believe that “architecture can be a social tool” and that “buildings are living things that are creating a new world ecology.” But what truly sets him apart from his contemporaries is his unwavering focus on matters that he can actually change. So, at this point, he’s diligently focused on the new Bajaj Institute of Technology in Wardha, which is a complete urban fabric, rather than being just a cluster of campus buildings. He is also working on the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in Mumbai and the two million square foot Eye of Wisdom laboratory in Shanghai, which will house 2,800 scientists working on a cure for Alzheimer’s Disease. It is such projects, which allow him to work with “people more intelligent, insightful and brilliant than I am, driving my spirit and imagination,” concludes Benninger.