Wizards of objects. A unique lens to materiality. And a global perspective to India’s artisanal heritage. æquō’s first group show is surprisingly homogenous given the disparate practices and craftspeople that have joined forces to create Kothi. In a conversation with Florence Louisy, Creative Director, æquō and the curator of Kothi, we deep dive into the ideas and aspirations of the show alongside the collectible design gallery located in the historic precinct of Colaba. “The dialogue between æquō and our collaborators started around materiality and techniques rooted in India,” says Florence.

Kothi, the Hindi word for bungalow, features the works of six designers—Sudheer Rajbhar’s Chamar Studio, Frédéric Imbert, Valériane Lazard, Wendy Andreu, Cedric Courtin and Florence Louisy herself in experimental collaborations with Indian artisans. It questions and plays with the idea of form and function, pushing the boundaries of material exploration, all in an endeavour to investigate, rediscover and document Indian crafts.

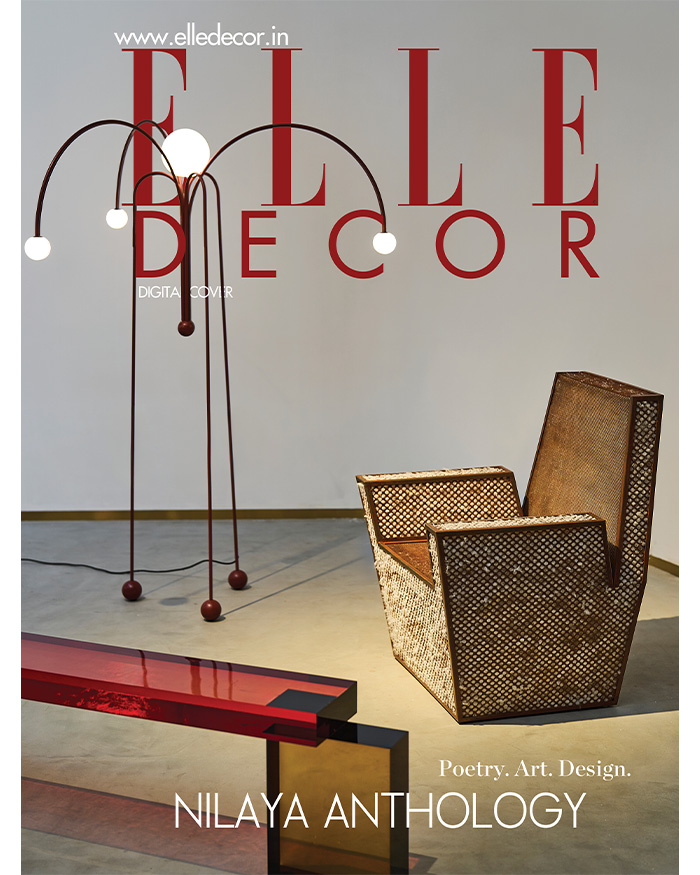

As the curatorial note for Kothi reveals, “In this intimate setting, intended to feel like the home of a collector, raw objects that are still in-process sit confidently next to impeccably finished pieces of collectible furniture. These are not juxtapositions, rather a balance that is the signature of æquō.”

While there are no deliberate juxtapositions, the result of the exploration of the crafts, karigari and the engagement with international designers translates into a debate between art and utility. Between what is perceived and what actually transpires, take for example, the Pocket chair by Chamar Studio that takes inspiration from the fall of fabrics. It illustrates the illusion of softness and a gentle cascade but is surprisingly sturdy and rigid. Chamar’s signature blue material made from blue tarpaulin debuted with a line of handbags and fashion accessories. But at æquō, Chamar reshaped their recycled rubber into a furniture giving a voice to their strong and sensitive process-based practice in Mumbai with the Dalit community.

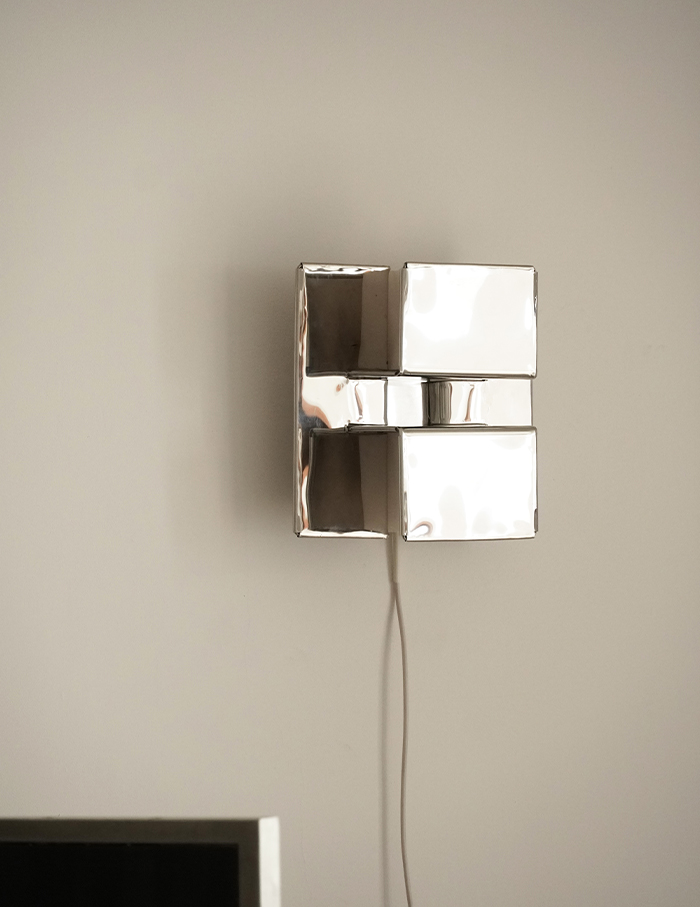

“There are also certain styles of local crafts that I have linked with specific designers sharing the same process, with a completely different culture. Like Wendy Andreu and her stylish construction style, now linked with the Tin Trunk Makers in the hub of Mumbai and their amazing skills to shape metal sheets. Or Frédéric Imbert and his sculptural and mindfull process introduced to this 4000 year old technique called Dhokra which we work with in Chhattisgarh,” explains Florence.

There are many common threads that emerge and bond the pieces together—from the contrasts, the play of paradoxes, the idea of sensitising patrons to new aesthetics and social contexts. But Florence is clear about the larger overarching goal, at æquō, “One way or another, this cultural fusion creates a rediscovery of ancestral as everyday techniques that is to me the key of collectible design. It is important to me to not focus only on the incredibly refined Indian craft but also the ones from everyday needs, and turn it into cool designs, sculptural, poetical. Giving a voice to everyone’s skills through æquō.” And when probed about overtly sculptural or abstract furniture blurring the boundaries between utility and art, she is quick to quip, “In my opinion, a successful piece is one that you never want to discard. It’s an object that we look at, and that tells us something.”

Witness this group show of experimental craftsmanship collaborations at Kothi, exhibiting at æquō, First Floor, Devidas Mansion, Colaba, Behind the Taj Hotel on 24th November, 6-9 pm.