Produced by Mrudul Pathak Kundu

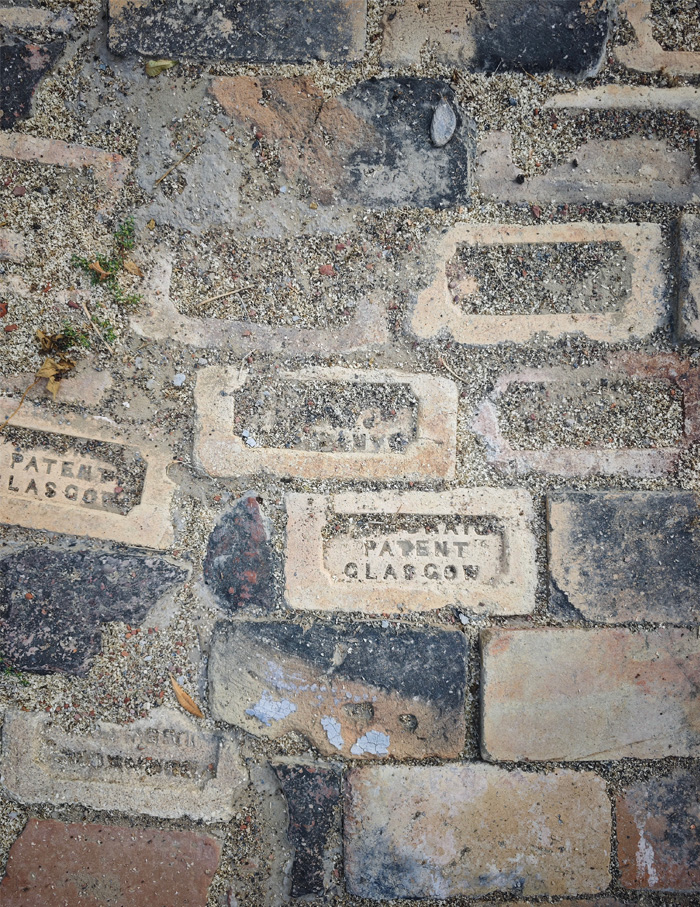

It’s a funny thing — how history hides in plain sight. It is a hot afternoon in Hisar, this quaint little city in Haryana. As we walk the grounds of the Tayal household, which was once a factory, we find a series of bricks beneath our feet, plastered over a concrete road. They are stamped ‘Gartcraig Patent Glasgow’ and bear the archetypal grooves.

We are not excavating nor scavenging for treasures, but recceing the property for our story, to frame and photograph the best vantage points. This estate dates back to the British era, with two historic homes occupied by the family. It also houses offices and industrial buildings that date back to the 1800s.

Hisar has been an important administrative region for Mughal and British rulers alike. And if this overture of history conjures imagery of magnanimous edifices and gilded details, then let me turn the page to a place where heritage is not confined to grand monumentality or nostalgia of the past, but in the fabric of everyday life.

It is in the layers, architectural quirks and collective memories in Hisar where heritage finds its place. This trip, the brainchild of Bindu Manchanda, took us on a journey to explore the untold heritage and vibrant culture of lesser-known towns like Hisar.

Four homes and their stories quietly preserve the history of India’s past, offering a reminder that heritage is not defined by grandeur alone. The first home — the one with the Glasgow bricks on the road, is where our journey began or what laid the ‘foundation’ of our trip. A third-generation resident now, Sumita Tayal moved to Hisar after marrying Mukul Tayal.

“My marital family, the Tayals, made its wealth by supplying hay to the British army for the Afghan wars. They bought this land from the British who had taken over Hisar in 1803, subsequently building a cotton ginning factory in 1889.”

Cut to the present day. As we gather in their lounge area, Sumita tells us, “This was a godown where cotton bales were stocked till the early 1900s. From then till now, from form to function, this structure has gone through so many transformations.

The Tayal factory estate is one of the few industrial heritage sites that is still thriving. The godowns have been restored and turned into living spaces. How the previous generation took great pride in its history sets an example for the rest.”

She points to the lofty double-height exposed brick wall that separates our lounge from the living area. “This was all cemented and thanks to INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage) I learnt how to remove the cement. We chipped it away delicately with a screwdriver to reveal this lovely brick wall.”

The brick wall under observation is not constructed from those Glasgow bricks but the Lakhori type which were prominent during the Mughal rule in India. Aesthetically, they do add textural and visual gravitas.

The Tayal home and estate was only one part of Sumita’s journey with heritage. Earlier on she had established contact with Bindu Manchanda, who had presented a proposal to revive the crafts of Hisar for the city’s INTACH chapter, leading to their serendipitous meeting.

Bindu, who also conceptualised and spearheaded this story on Hisar, has been at the forefront of many restorations and revivals across architecture, textile, craft and allied cultural heritage. Bindu believes that heritage also lies in the overlooked details — small, often unseen elements that reveal traces of the past.

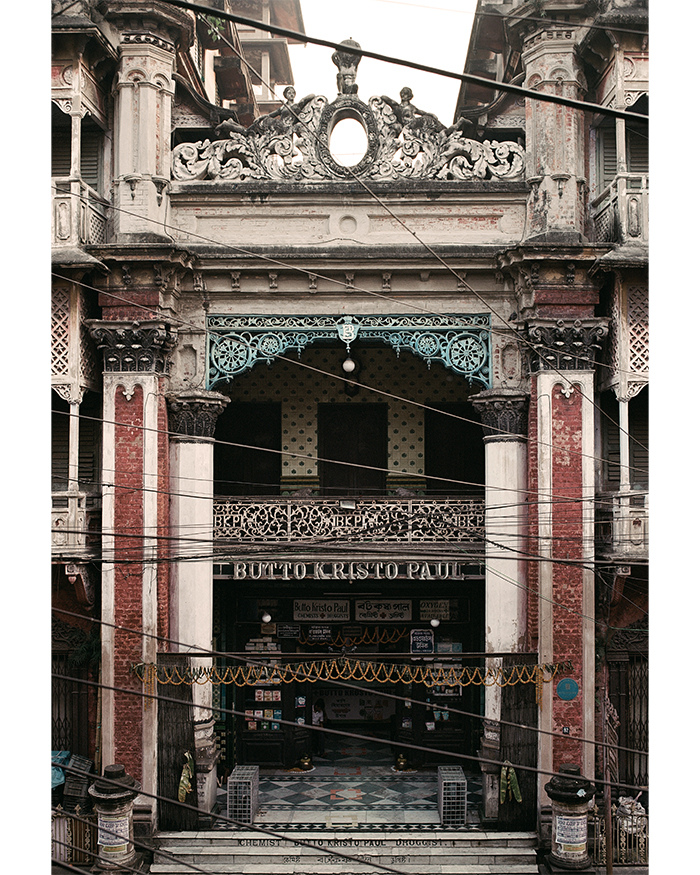

Our second stop is a home with an interesting mix of elements tracing back to Agra and even Britain: Ishar Niwas. Built in 1901, it has a striking wooden entrance with silver and brass knobs and a facade made of red stone from Agra. The inner courtyard features floral designs made of limestone mortar, crafted by artisans from Rajasthan. Above the courtyard are cast iron grills depicting a portrait of the late Queen Victoria!

One of the owners, Parnita Singh shares, “These railings were brought in from Britain in the late 1800s. The wooden facade was made in Agra by Muslim craftspeople and brought to Hisar on camels.” Parnita and her husband Jagdeep Singh currently reside in their portion of the haveli.

Parnita adds, “There was an older mansion behind this home. It was demolished since there were many owners, redevelopment would entail legal complications.”

I wonder about the pragmatism of preserving the old versus letting it go for the new. We perceive heritage as a sentimental endeavour that is driven by the beauty, legacy and irreplaceable craftsmanship of the past. I wonder if the homeowners do not realise the value of these buildings? But then, who am I to judge what deserves preservation or what holds value?

Sumita offers a perspective, “Heritage can also be painful. You and I look at it through rose-tinted glasses. This town and its people have lived through centuries of heritage and witnessed significant destruction and invasions, leading to a certain disdain for the past.

For those who experienced the partition, caring about a single monument isn’t part of their psyche; they faced greater struggles, often prioritising stability over heritage. Many who relocated left beautiful heritage behind them. For them, building new lives and finding peace takes precedence.”

But Bindu smoothes over the dilemma as she adds, “But forgetting the past can also hinder the future. The oldest buildings are the most sustainable. They reflect a deep understanding of the environment and materials.”

Bindu turns our attention to Rakhigarhi, an Indus Valley Civilization archaeological site in Hisar, “Their traditional ventilation and water management systems sustained them for generations, proving that effective solutions exist beyond modern-day air conditioning.”

Our third home is a mansion with cement and concrete facade. Its curvilinear profile and floral motifs are not entirely Indian, European or Mughal. It dawns upon me that heritage is also a bridge or even an olive branch? It connects disparate times and cultures, a thread weaving continuity through change.

As we unpack perspectives with Bindu and Sumita under the shade of a majestic Banyan tree at the Tayal grounds, I realise that we are tracing a fabric interwoven with many threads of identity.

If there was ever a conclusion as gratifying, it would be this fourth home — a stunning but curious kothi , as Sumita calls it. Sheikhpura Kothi is set amidst the agricultural fields of Hisar. Owned by Arvind Chowdhry, the grandson of the philanthropist Sir Chajuram Chowdhry, the building was designed by F P Dinkelberg, a celebrated American architect.

It blends classical French influences into its imposing Renaissance-styled structure. It is currently used as a holiday home and rental operated by WelcomHeritage.

In almost impeccable condition, with a glorious entrance lobby, the home combines elements of a country home, and is distinct from palaces or havelis, featuring Tuscan-style terrazzo pillars characteristic of the 1920s. While not monarchical, such homes were owned by affluent merchants and aristocrats. Each had its unique quirks, like how this one has a colonial-style bed integrated with a fan.

The home with its grand staircase and eclectic finds stands tall and proud, emblematic of our collective understanding of heritage. To that effect, will we ever really find a collective consensus on heritage? These homes reveal a hidden truth about history: it is not always celebratory or easy to honour the weight of complexities and contradictions that they carry.

Sometimes they are uncomfortable reminders of struggles and survival that the earlier generations may prefer to forget and erase. But beauty finds ways of residing even in the pain and neglect. It embodies resilience, endurance and the shared experiences that shaped us.

Heritage, I realised, is as much about adaptation and survival as it is about memory. It is about creating something not just to endure but also to evolve. It’s not a static monument, it’s an evolving narrative, layered in time, inviting us to acknowledge where we come from and how we wish to shape the future.

Read more: City Beautiful, City Perfect: Discover the Chandigarh behind Corbusier’s utopia