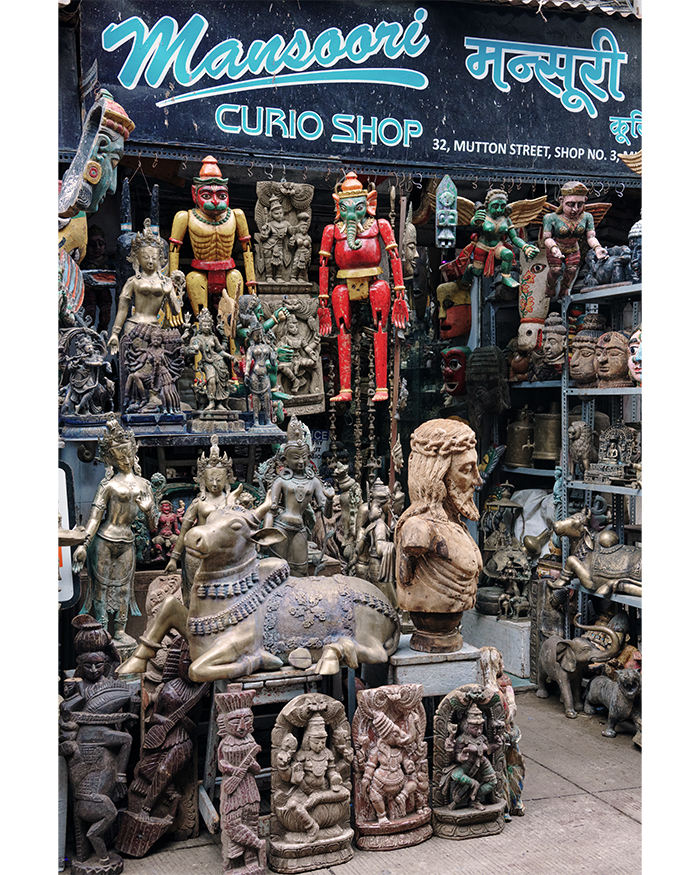

Chaos, cacophony, colour, olfactory overload, layers upon layers of things, textures, sounds and people can feel like an assault until you realise it is also a system. People, climates, calendars, languages, beliefs, trade routes and histories overlap in India’s bazaars. Tarpaulin sags with monsoon water, shop lights burn too white, bangles stack into shimmering towers, spices sit in open sacks and shallow tins, and saris cascade into bright blocks of colour. A vendor’s call ricochets off corrugated shutters, a scooter horn pushes through the crowd, and somewhere a radio competes with a prayer bell, both swallowed by the market’s hum. As the threshold between street and shop dissolves, storefronts become billboards and countertops at once, and options are thrown at you in volumes.

Come festivities, and extra strings of LED lights are pinned to shutters, fresh posters and rate-cards are taped over older ones, temporary counters added to the sides of every street, there are more hands billing and packing, more bundles moving out in bulging bags. Our markets are crowded because they are efficient, loud because they are competitive, layered because the street must also behave like a catalogue and a warehouse. Across cities, they speak the same language of abundance, yet no two markets are identical. They are calibrated to their own clientele, religious majority, seasons and buying habits dictated by each. A jewellery shop gears up for the wedding season, a spice lane for daily replenishment, a repair bazaar for salvage. The only constant is maximalism, amidst many variables.

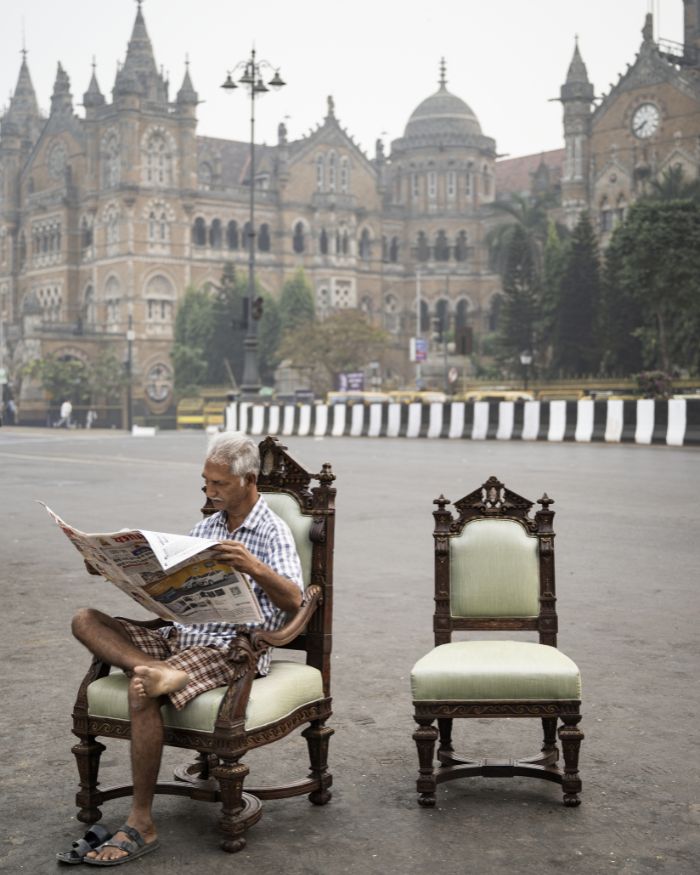

And sometimes, these markets feel like the city’s counter-image and antithesis. While the modern city advertises its aspirations through its glass buildings, orchestrated order and blankness, the bazaar must survive in the narrowest, messiest parts of town because it still does what the new city cannot. Aggregating trust, competitive prices, repair, credit and choice in one walkable place, at a speed and affordability that no showroom can match, their histories go back to empires, port cities and caravan routes because these places of trade outlived every redevelopment cycle that followed.