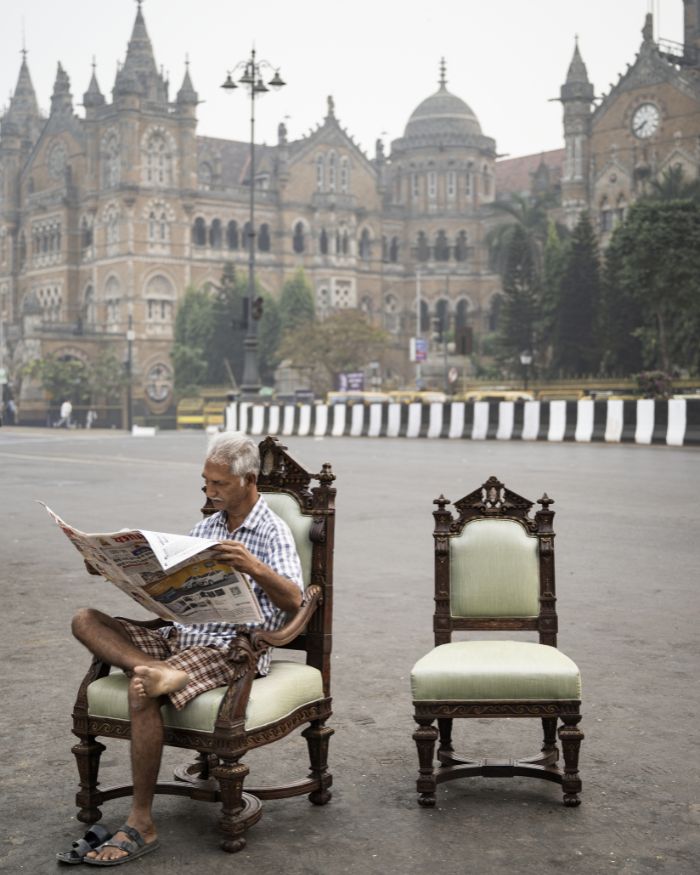

Less is more is not part of the Indian aesthetic. Every element, whether colour, imagery or embellishment, is used to the full. Every surface filled to the maximum. Unlike the Japanese or Swedes, we don’t do minimal! Negative space, an important part of design elsewhere, is not a part of the Indian tradition. When a master carver encounters a grain of rice, he engraves an entire Taj Mahal, or the text of the Hanuman Chalisa! Given a temple wall in Khajuraho or Thanjavur, he fills it with hundreds of figures — a whole social history of its times. The Madurai Meenakshi Temple reportedly has 33,000 images! A Kashmiri papier-mache screen or Jamewar shawl will blossom into a garden of flowers, each intricately delineated and imagined. At its best this approach is multilayered and magnificent, at its worst it is cluttered and overdone. It worked well in India’s vast palaces under the blazing sun, each royal court trying to outdo the other in splendour and show. Like everything, in the 21st century it needs reinvention. Ornately embossed silver furniture that looked magnificent in marble-floored halls with towering ceilings seems inappropriate in a three-bedroom Bandra apartment in Mumbai. Just as the gargantuan 10-course dinners of our ancestors don’t work for our 21st century digestions! In India, the term design is often confused with ornamentation. Form, function and finish play second fiddle. The idea of design is used like an aerosol spray in a smelly bathroom. To pretend that obsolete, stale things are fresh! It’s no coincidence that when I first started working with interior designer Shona Ray in the early 1970s, people thought an interior designer and an interior decorator were one and the same: the person who applied fresh paint on walls.

It is important to realise that design is not just about making things look good, but a way to examine, understand and reshape our lifestyles, our society and ourselves. A look out of our windows at the jumble of concrete, electric wires, tangled traffic and mutilated green spaces for instance and the confusion and angst of those who live in it, shows how bad contemporary India has been at designing its urban spaces and safeguarding its environment and heritage. Our spaces reflect ourselves and we still seem to be searching for the identity of that 21st century Indian. It is often an uneasy Bollywood amalgam of the past mixed with what we think is trendy in the West. What is the key to India finding itself an exciting and unique new 21st-century identity — both aesthetically and culturally?

A country’s identity is reflected in its visual aesthetic — be it architecture, clothes, domestic interiors or artefacts. Recently, over the last decade or two, India (and with it the world) has woken up to the fact that traditional crafts and textiles are not just a picturesque part of our past, but can be a fantastic part of our future: enhancing our lives, homes, clothes and identity. Adding something uniquely different — Indian but also contemporary.