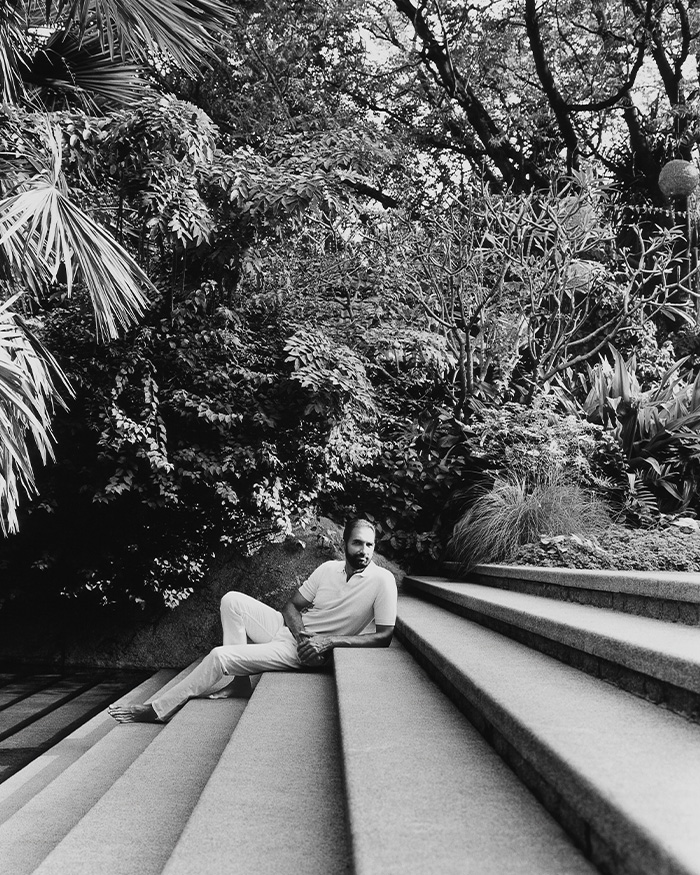

Sanjay Reddy is the kind of maximalist you would hardly associate with maximalism. He is not flamboyant or loud. “I knew minimalism, but I heard about maximalism only when Sabyasachi made the term mainstream,” he laughs when I tell him that we want to profile him on maximalism. Wearing white linen, Sanjay is a tall man with a presence, but he is also quiet, observant and patient. He carries none of the bravado usually associated with scale. But his life is marked by it. Big systems. Big responsibilities. Big public expectations. And even bigger cultural stakes, but that is completely his choosing and we have two magnanimous airports (Mumbai and Bengaluru) to thank him for.

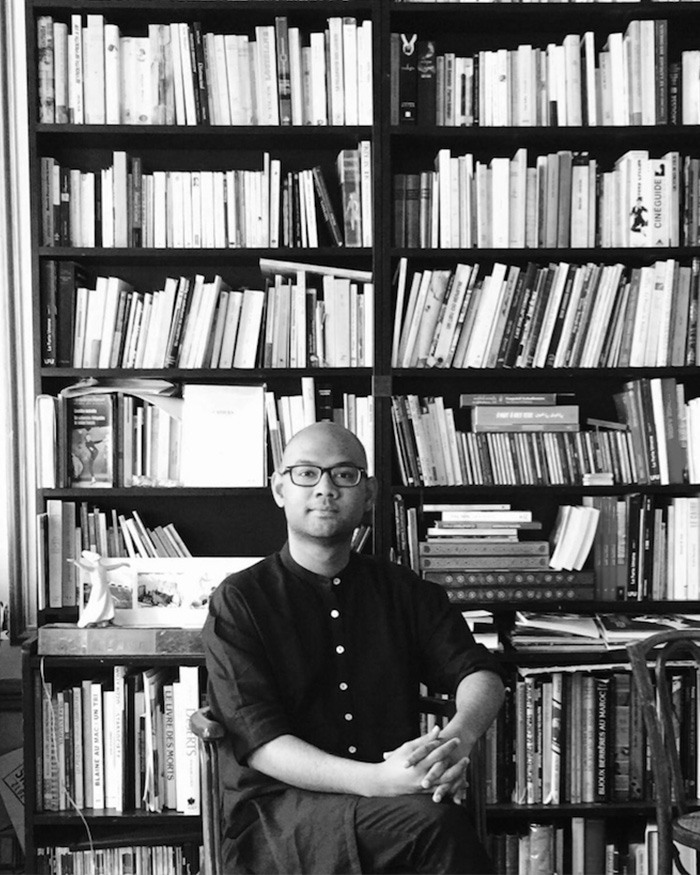

“There are two parts to me,” he says. “One is a collector who loves art, another is a creative who likes to explore.” It sounds simple, but it explains almost everything about his choices. Sanjay’s design instinct began far from the world of museums or architects. It emerged when he took an interest in designing power plants, which are usually dismissed as technical and utilitarian. “Most people find power plants boring,” he laughs. “I enjoyed the system. I designed one with a lake and boating, with beautiful botanical gardens,” says the man with a bachelor’s in industrial engineering from Purdue University and an MBA from the University of Michigan — Ann Arbor.

His eye for aesthetics and instinct for order arrived even earlier. As a child, he travelled with his parents through France and Italy, exposed to European art and collecting traditions. Though the European aesthetic never resonated deeply. But things changed in 1994, when he met the late Jagdish Chandra Mittal, one of India’s foremost collectors of Indian art and miniatures. “It ignited something in me,” he says. He began collecting Indian art pieces from the 10th to the early 20th century. “I do have some modern art, but I don’t find a calling there. I don’t collect to invest, I buy what moves me. It could be simple, inexpensive or priceless.”

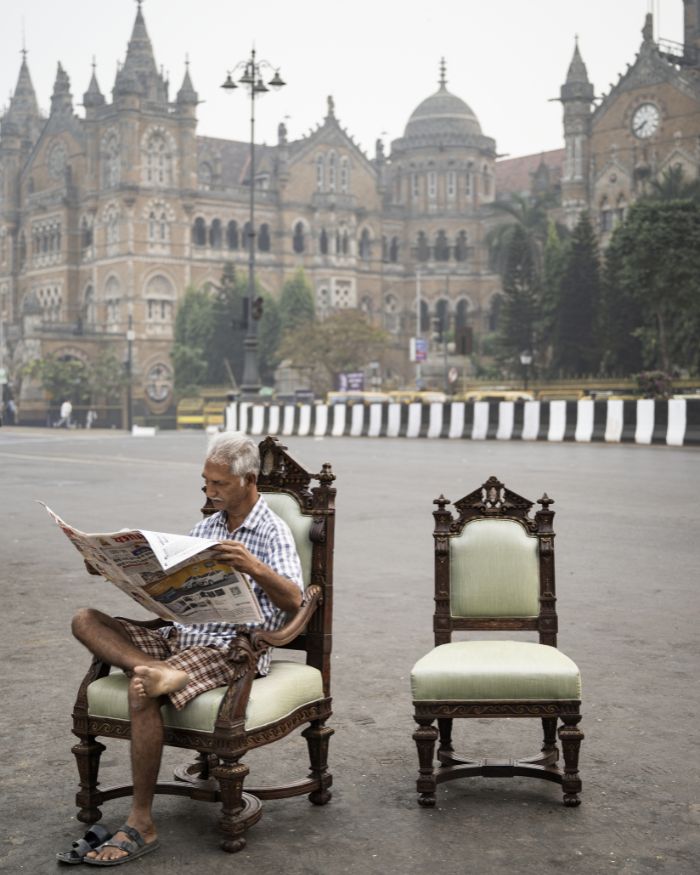

The businessman could have kept his mind and heart at opposite ends when he won the tender for Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj International Airport Mumbai, and operated simply from a commercial, capitalist standpoint, but he gave India something that we had never seen before. Mumbai Airport could have been a standard glass and steel terminal, indistinguishable from any other in the world. Instead, Sanjay treated it as a civic statement and a once- in-a-lifetime opportunity. A public space where India would tell its own story without relying on Western templates. Designed by SOM (Skidmore, Owings & Merrill) under the creative leadership of Sanjay Reddy and GVK’s in-house team, and Sandeep Khosla, the terminal reorganised the idea of arrivals and departures. The architecture is clean and expansive, with a long-span roof canopy shaped by peacock- feather motifs. The headhouse roof system includes 272 skylights (28 major and 244 minor) spanning over 30,000 sq m, pulling daylight deep into the terminal.

The art programme became the terminal’s identity rather than its ornament. Sanjay and Rajeev Sethi mapped 7,500 artworks along the actual movement pattern of passengers: departures, security, travelators, arrivals, baggage claim. Following the logic of movement, large pieces were placed where passengers slowed down (security, escalators), smaller details entered high-frequency zones (travelators, piers). Sculptural works stood at nodes. The scale ensured that in a country as diverse as India, people did not just see India in general; they saw something that felt like home before they boarded. It was a way of folding culture into the country’s busiest transit system.

By being calmer, organised, coherent, with a moment to pause and appreciate art, Mumbai Airport runs against the common perception of Maximum City, proving that public design can actually streamline public disorder, a state that the city has grown attuned to for too long. Most collectors guard their objects in secrecy. Sanjay’s greatest work is public: millions move through it every day, unaware they are inside the country’s largest exhibition. “I wanted to build the best airport in the world,” Sanjay enthuses. People assumed that it was an impossible feat given the size of the airport. “Delhi is 5,000 acres, while Mumbai is less than half that, at 1,300 acres,” he states. While Mumbai Airport brought art into the country’s busiest bloodstream, Bengaluru Airport is its counterpoint: “A Terminal in a Garden” for a city that has been steadily losing its trees and weather to urbanisation. Bamboo columns, stone floors, brick, water and landscape do the work there that art does in Mumbai. Neither project is modest in size, but both are unusually precise about mood and place. That is where his version of maximalism operates, it is in the scale at which he is willing to think about how Indians move, look and feel. When asked what fuelled his ambition, he offers an unexpected admission, “It goes back to what it means to be Indian and how we have evolved over the last 60 or 70 years since independence. For a long time, I felt there was a lack of confidence, even a lack of pride, in being Indian. It seemed built into our DNA. I think it comes from not having a secure sense of identity. We tend to put ourselves down in front of others. I don’t know the exact reason for it. You could blame colonial history, or the fact that we are so diverse, with so many languages and cultures.” But he sees a shift now, as he tells us, “But that is changing, very fast. Especially in the last 10 or 20 years, younger Indians are returning to their roots, reinterpreting what heritage means, and feeling confident about being Indian.”

To him, heritage is decision-making, it is what he insists on building, and what he chooses pride in. Even his own collection is free of instruction. “I tell my children: keep it, sell it or give it away. It’s theirs.” And that is where the contradiction resolves. Sanjay Reddy does not chase scale, but scale finds him. He is not a maximalist by temperament, but his work argues otherwise. He is the rare figure for whom big is simply the size required to express conviction. India has always been a maximalist country. Sanjay Reddy is one of the few who knows how to make that instinct work.

Read more: Princess Esra Birgen Jah, a minimalist in the Nizam’s Palace