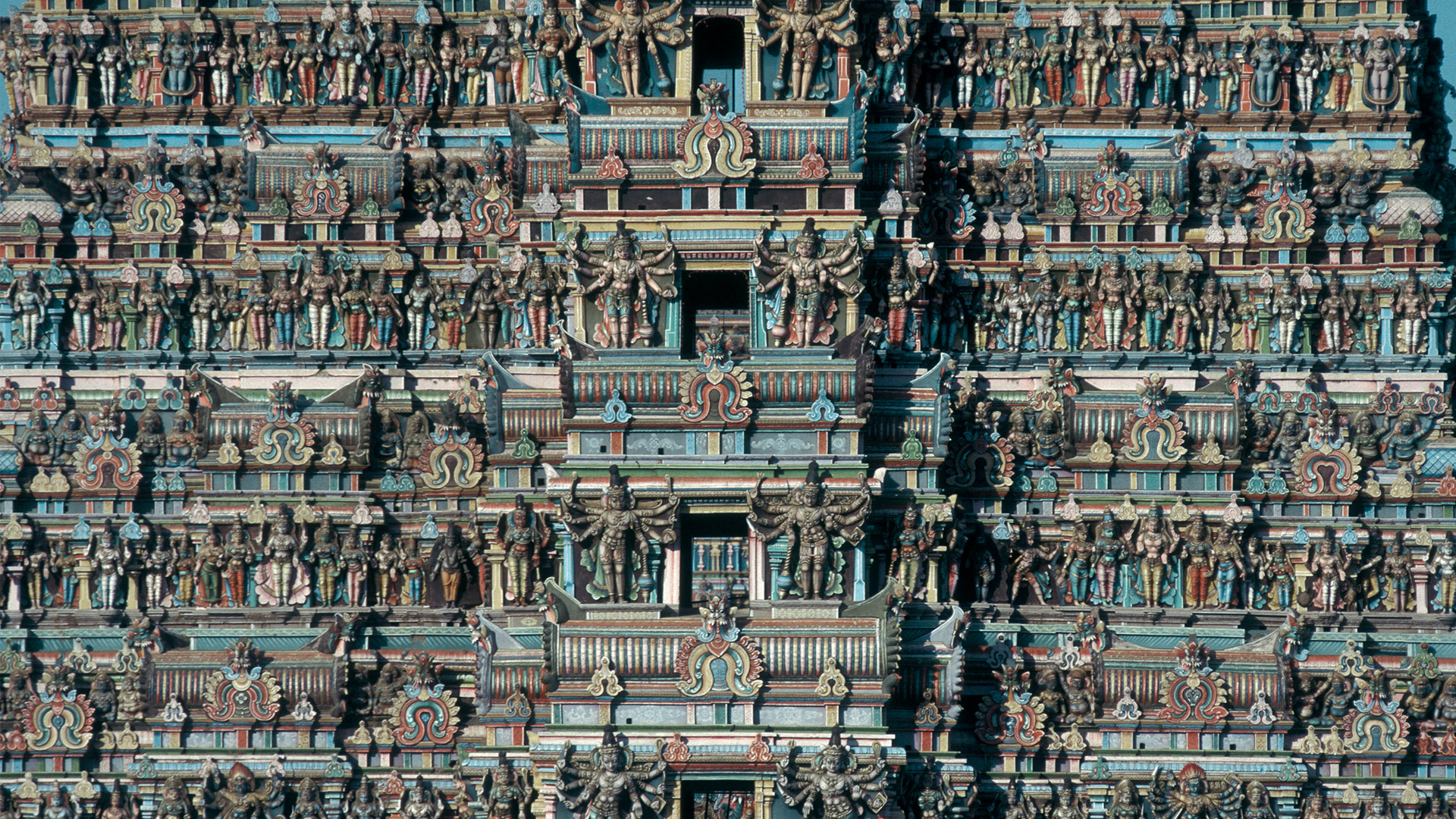

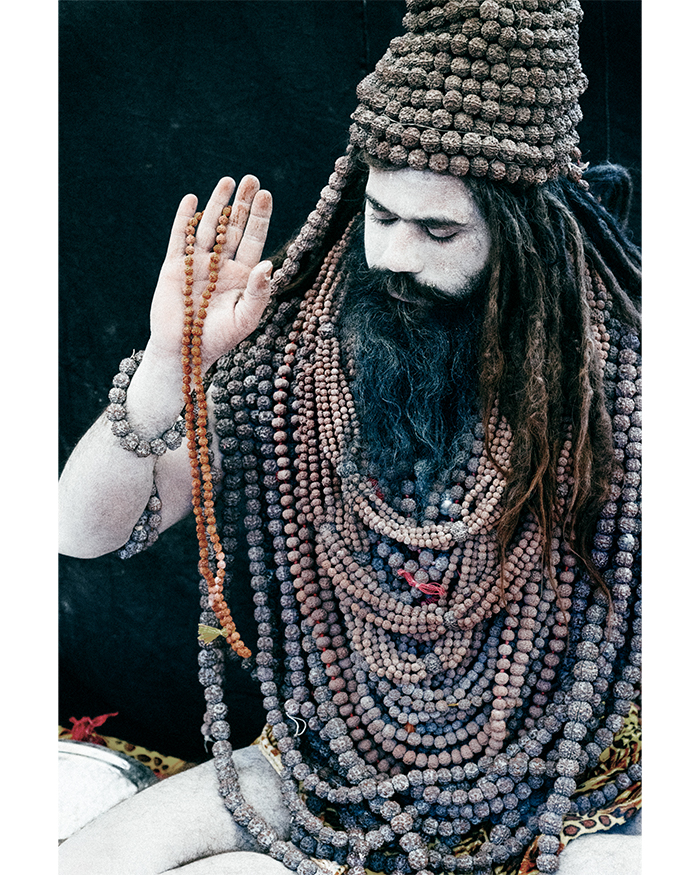

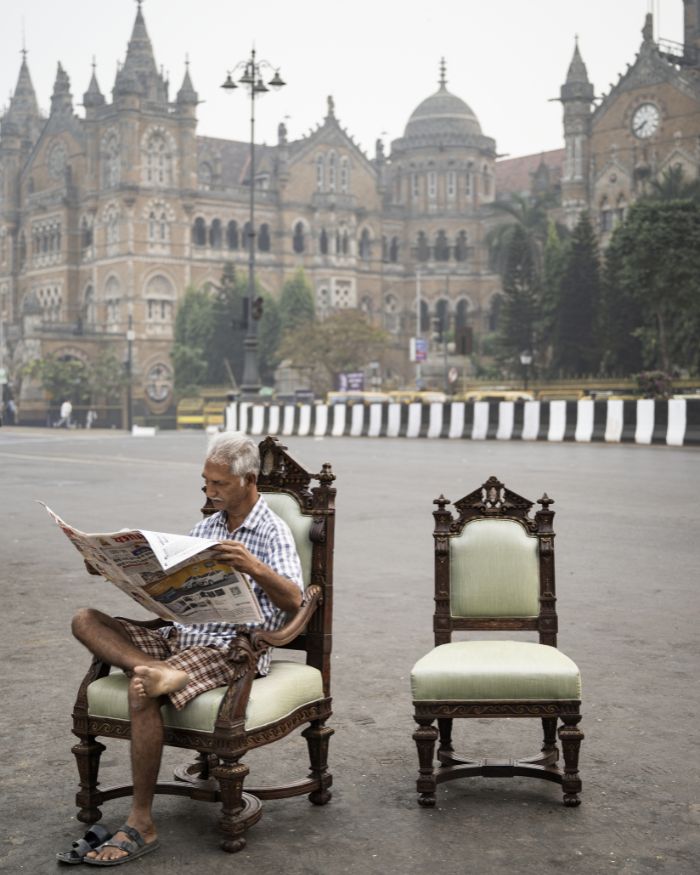

India belongs to so many people beyond the borders of this oasis-like country. Its spirituality and its monumentality could never be contained, right from its ancient past. This isn’t a note on history, it’s a note on nostalgia of a collective intuition that developed into religions that manifested faiths, that built a materiality that one can feel, one can visit, and one can meditate upon. An infrastructure that isn’t based on a set compendium but a living tradition so ancient that not one book, or one sage, could have possibly built or led it. It was always open, to spread, to be understood, to be adapted and adopted. This is the legacy of India’s maximalist faith, which still lives and breathes beyond its own borders.