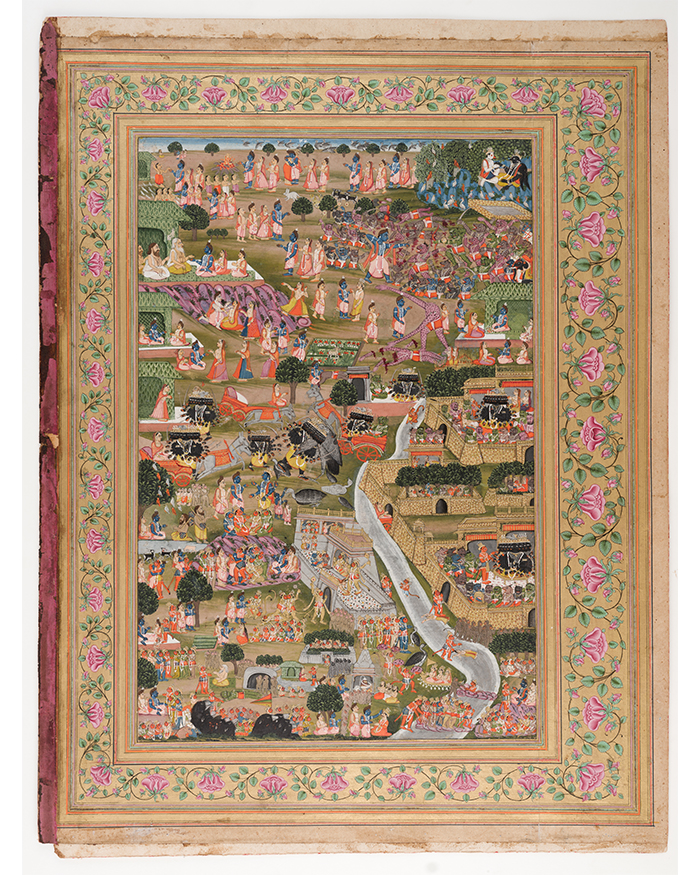

No language of the Indian subcontinent offers a single term that encapsulates maximalism. For the West, maximalism is an aesthetic and philosophical trend that stands at the other end of minimalism in a binary spectrum. Whereas in India, our cultural roots and aesthetics are intertwined with the soul and the sacred. And from that springs both a celebration of life and a spiritual quest, resulting in an exuberant expression of the senses along with the austere restraint of an ascetic. The underlying impulse stems from the same source where opposites and contradictions (maximalism and minimalism), abundance and austerity, coexist naturally and easily. The tradition of cladding the body with gold brocaded ceremonial textiles in lush, vivid colours or in austere white woven cloth was contextualised by the occasion and not as a trend. Even austerity is imbued with serene beauty, poetic detail and a contradictory sense of fertile abundance.

The Vedic tradition of adornment goes back many millennia, based on the belief that the body is a temple where the soul resides. Personal cleanliness was practised daily with ritual bathing through the use of fragrant oils and pastes. In the Rig Vedic dawn hymns, women were described as “anointed with unguents and resplendent as the sun,” while temple dancers bathed in sandalwood and turmeric before performing aarti. Layering, a fundamental concept in adornment, begins with oils for the hair and body, often combining up to a hundred herbs and flowers and fragrant resinous gums in one single oil.