Produced by Mrudul Pathak Kundu

Human history is filled with stories of tribes, traders, invaders and large swarms of the populace migrating across continents. The reasons were multivaried: yet another famine, unprecedented climate change, or the occasional (often) tyrannical ruler. But in 16th-century Mughal India, a peculiar shift was occurring — idols of Hindu deities were abandoning their shikhara-topped temples, and were being moved by worshippers into their own havelis. Was it out of the fear of persecution, or to bring God closer to home during those turbulent times? These havelis in question were no ordinary residences. As trade flourished, wealthy merchants often invested a fortune into constructing lavish, richly ornamented structures that signalled their monetary and cultural affluence. One such structure stands alongside artist Amit Ambalal’s residence in Ahmedabad.

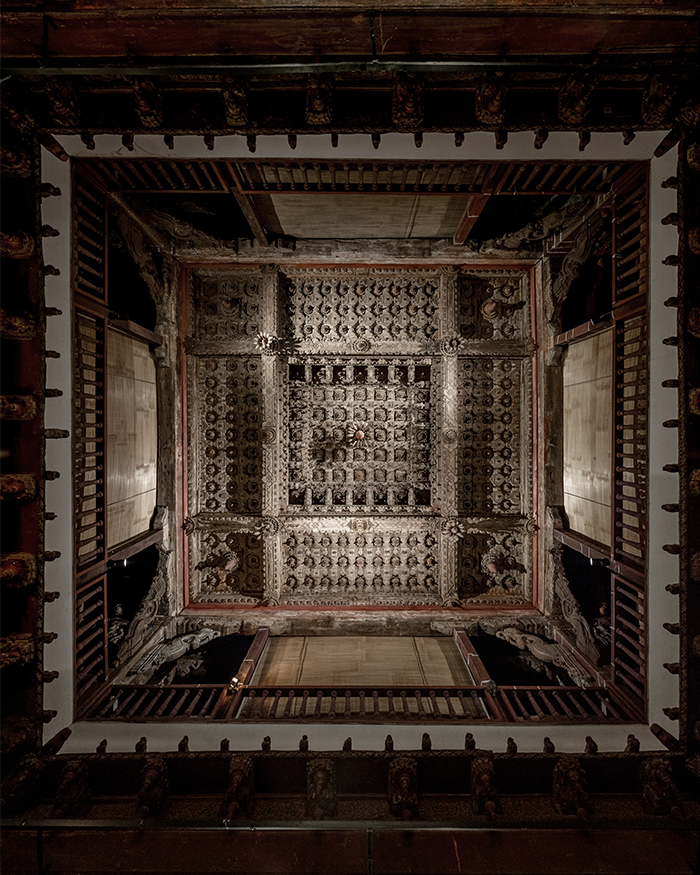

The two-storey haveli, dubbed Kamal Chowk, is a greater sum of smaller, infinitesimally intricate motifs that loop across its double-height entirety. Four well-adorned pillars and plinths conceived in reds, yellows and faded blues uphold the true piece-de-resistance: the ceiling, featuring what looks like innumerable floral motifs carved by artisans from Patan centuries ago. The walls display Amit’s extensive Pichwai collection from the Nathdwara School of Painting, each one a riot of colour that depicts Lord Krishna as Srinathji: the god’s younger, impeccably adorned version, balancing the Govardhan hill on his little finger. For those accustomed to seeing such works of art in white cube galleries, prepare for the sheer grandeur of this sight to eclipse anything you’ve ever seen before.