Design

What makes a metropolis? Parallel Cities at Nature Morte’s Mumbai gallery searches for answers in the urban experience

MAY 18, 2024 | By Namrata Dewanjee

Each reading of Invisible Cities, reveals something new. In architecture school, while we were still finding our footing with this strange thing called design, our professor handed us a copy of the infamous text. Daunted, dazed and equally hypnotised, we were smitten with Italo Calvino’s Venice. Turns out, we were not alone. Inspired by the same post-modern provocation, Andrea Anastasio curates a set of urbane artworks, from Italy and India under an exhibition titled Parallel Cities II at Nature Morte’s Mumbai gallery.

Contained within stark concrete walls with slivers of the city peeking in, the parallels between Calvino’s world and the metropolis outside are all too apparent. Constructed in imagination and desire, the urban condition is part subversion, part bewitchment. “And Artists,” muses Andrea, “are cities in themselves.”

Cities and memory

“There is a certain possible universality that one can relate to in the story,” says architectural theorist and critic Kaiwan Mehta. This human condition perhaps echoes the loudest in Diwik Singh’s collection of objects that belong to grandmother Kasturi Devi. In her memory, Kasturi’s husband donned her sarees and ornaments. His sewing machine is placed carefully next to the window, beyond which are raw mangoes waiting to ripen in the summer sun.

“There is a domesticity to this artwork,” declares the curator. “It’s an individual expression of life, mischievous, at times disturbing to someone but amazingly escaping any definition,” he expands.

In another corner, Mayank Austen Soofi’s copy of Proust stands like a wallflower in a “parallel city”, observing the scene with a watchful eye. Placed between two window panes that provide a portal to the speeding traffic, flamboyant colonial architecture and the network of invisible forces that shape the city, Proust seems to bring the undercurrents to the surface.

Speaking of invisible forces, Martand Khosla’s metal and wooden rollers deposit barefoot and chappal patterns on the floor in red brick dust. “Quite like kollam,” Andrea adds. “Almost all the materials that I work with in my art practice are from the world of construction. This material connectivity lies at the core of my practice that explores the constantly evolving urban condition,” says Martand. Ephemeral yet undeniably present, the footprints belong to the city itself.

Cities and eyes

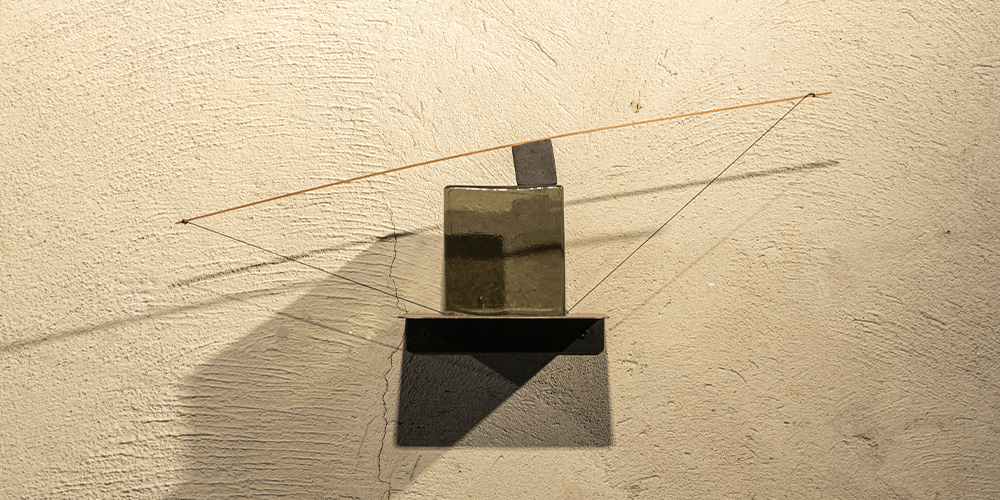

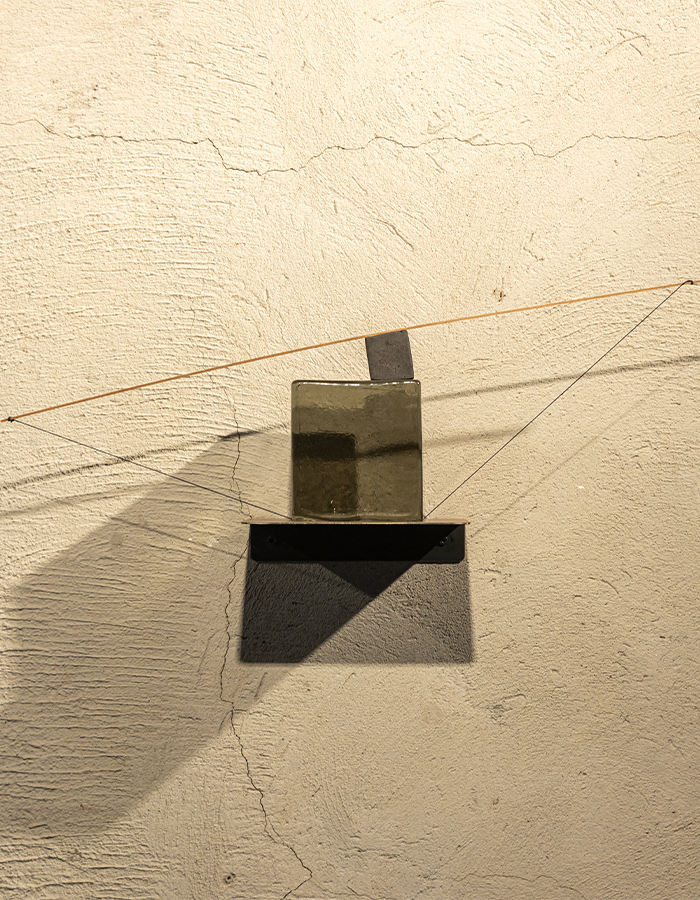

Andrea insists we stand at the threshold of the second room. From that vantage point, Alice Cattaneo’s exploration of instability, Dayanita Singh’s photographs of Mumbai theatres and Parul Gupta’s shifted square ricochet a narrative of perspective. It would not be far-fetched to say Calvino inspires an altered way of seeing itself.

As I move inside, the unreal colours of Dayanita’s photographs, catch me off-guard. Before me was the Venice I imagined. But it was not Venice at all! What makes the imagery of a city I have never visited so distinct in my mind?

I ask Kaiwan how he relates his Mumbai to this mythical Venice. “My Bombay and Calvino’s story come in conversation to help me view the city as a universal audience. There is a Bombay that everyone holds in their head. And Calvino’s texts are just that. They have an interesting ambiguity or they leave you in suspension. It’s there and not there. It’s seen and not seen,” he says.

Cities and signs

Alice’s unstable composition stands on a block of Murano glass — a slice from the Venice Laguna. But why does she choose this unconventional material? She says, “Glass processing, from its origin to the final object and the landscape where it is generated creates a metaphorical rhythm similar to the dimensions and changes of our cities. It is about a physical and emotional time marked by people’s movements and their inhabitation of space.”

On fragile soap blocks, Elisabetta Di Maggio carves the synergy and divide between a city map and the natural world. Stefano Arienti brings the same contrast through sketches on tarpaulin, bringing an informal materiality into the gallery space. Ayesha Singh’s wrapped flag stands suspended from the central pillar, taking a more political approach and abstracting the shortcomings of globalisation.

I wonder if Marco Polo were to find himself in this South Mumbai gallery at this exhibition titled Parallel Cities, would he choose to tell Kublai Khan about the sewing machine that sits by the window? The glittering red bricks of Viswanadhan that echo the ones sitting underneath the plastered facades outside? About the raw mangoes or how we carefully navigated Martand’s red brick patterns on the floor? Would they all become characters in their own right? From a distance, Calvino seems to answer, “You take delight not in a city’s seven or seventy wonders, but in the answer it gives to a question of yours.”

Visit the exhibition until 6th July, 2024.

Now read: Into the rabbit hole of bizarre: Tejal Patni exhibits Vichitra at Snowball Studios in Mumbai