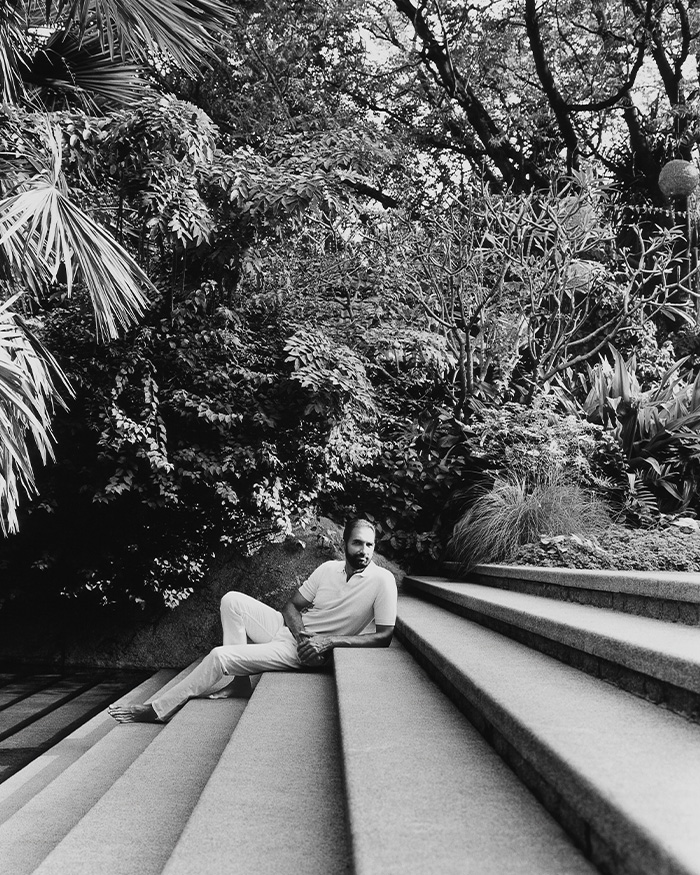

Portrait by Bikramjit Bose

Produced by Mrudul Pathak Kundu

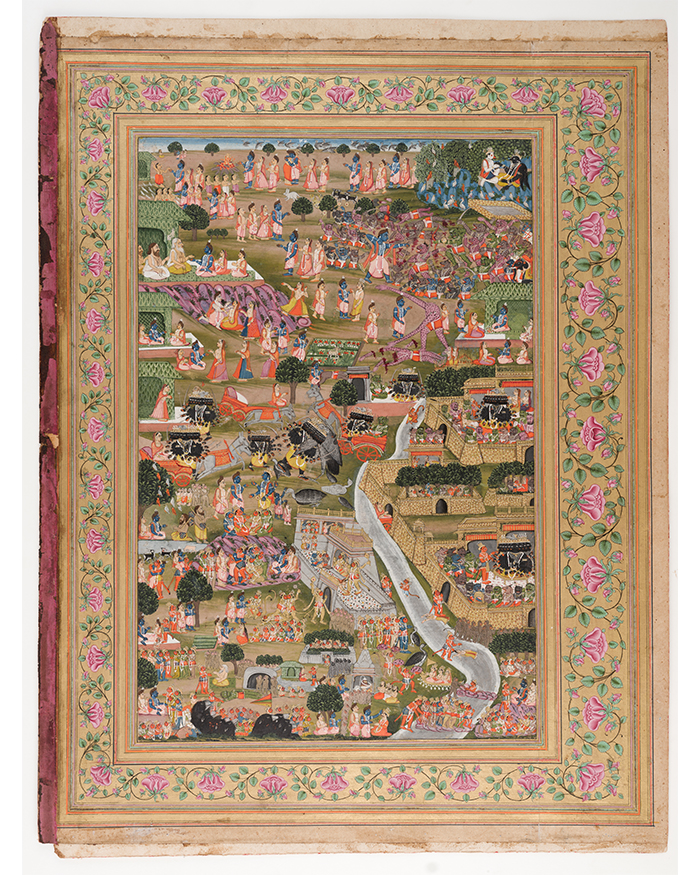

When I meet Yogesh Chaudhary inside the Jaipur Rugs gallery at Narain Niwas, he is surrounded by carpets that predate India. Pieces woven in nomadic tents, royal courts, villages and in countries that have now been renamed or redrawn. He stands in the middle of a collection (correction: an archive) spanning centuries of history. He is quiet, sharply dressed and stays out of the way even though the room moves around him. Not quite the visual shorthand of maximalism. My first question is if he ever thought of himself as a maximalist. “Not really,” he replies. “In fact, I was surprised. How do I fit in a magazine about maximalism? But it made sense when you mentioned the antique carpets. I connected the dots,” he says with a smile.

He bought his first antique rug in 2006–07. It was a Kashmiri piece from an old factory. The second was an Agra jail carpet, part of little-known history in which prisons in Agra and Bikaner ran weaving workshops. “Believe me when I tell you, I never bought carpets to sell,” he establishes congenially, “I was buying them to collect.” His buyers would see antique rugs stacked casually in the Jaipur showroom and would insist on buying them. One ended up in Anushka Sharma’s home, though he says he never intended to part with it. And then there were those that got away for entirely different reasons. His mother, he tells me, refused to let him place a rare 1920s Tabriz rug in their home. “It was a 100-year-old piece, with an unusual patina of purple, yellow and different hues that have faded away. And the colour tones were still beautiful. I bought it for a fortune,” he says before he tells us what then transpired. “And suddenly my mother declared that she did not want any old rugs in the house. My retail team was extremely excited when I took it to them, affirming that it would find many takers. I till date believe that those who bought it, are extremely lucky people.” At the same time, he is quick to establish that he is not a hoarder, articulating a distinction many collectors feel, “Hoarding is when you just want more and more. You hoard either when you don’t have money and want whatever is cheap, or when you have too much money and don’t know what to do with it. Collecting is different. You buy because you love the piece.”

It explains why most antique carpets only appear on the market when the original collector is gone and the estate is being dismantled. “I’ve almost never bought a carpet directly from the collector themselves,” he says. “It’s always their family who sells them. And it is usually because the collector has passed away.”

There is an emotional current that surfaces when he describes families approaching him because they want their carpets to be treated with not just care, but also love and respect, “People want to know their pieces will be cared for.” He recalls a family in Bombay who moved to a contemporary apartment where antique rugs did not fit and Yogesh ended up inheriting them. While he may have not begun with the idea of building an archive, he stands surrounded by fragments of material culture that museums chase, and countries will probably fight to reclaim. Take for example, the Kerman rug right behind him. With the patience of a kind teacher, he explains, “Kerman is a city in Persia. This rug is almost 120 years old. But see the red and blues, the primary colours? And then also the green? Now they were obviously dyed using natural colours. And they are small in size, because they were made in villages, using the finest wool available at the time. Till date, the carpet is extremely soft to touch, the wool is pristine. And I know that no one can recreate this carpet because the wool does not exist.”

He goes on to tell me more, “You see the Tree of Life, rose motifs, because they were obsessed with roses, and animals like deers.” I ask him a trick question, “Given everything that we have spoken about today, what in your experience encapsulates the idea of maximalism?” He thinks for a minute and tells me, “One of my favourite places in the world is the Abhaneri Bawdi stepwell. It is a two-hour drive from Jaipur. It has 13 storeys, and you step down to reach the water. It could have been a purely functional pit, yet, the interiors are detailed so painstakingly. And in the case of most stepwells, their beauty is not even visible from the outside, only seen when you descend towards the water. To do so much more, when even a pit with the same engineering could have functioned just as efficiently, is maximalism according to me.”

“So you know what is maximalism,” I chide him. He laughs, “The dictionary meaning, yes.” By that definition, he has been a maximalist for years without naming it. Buying rugs he did not need for his business, learning to read motifs and dyes like books, turning pieces into archives that span centuries and geographies. The stepwell at Abhaneri and the rugs in Yogesh’s collection are fundamentally similar: to go far beyond what function demands. He may borrow the term from the dictionary, but the endeavour is entirely his own.

Read more: Across the high and low, how ordinary life appropriates public spaces