Produced by Mrudul Pathak Kundu and Shriti Das

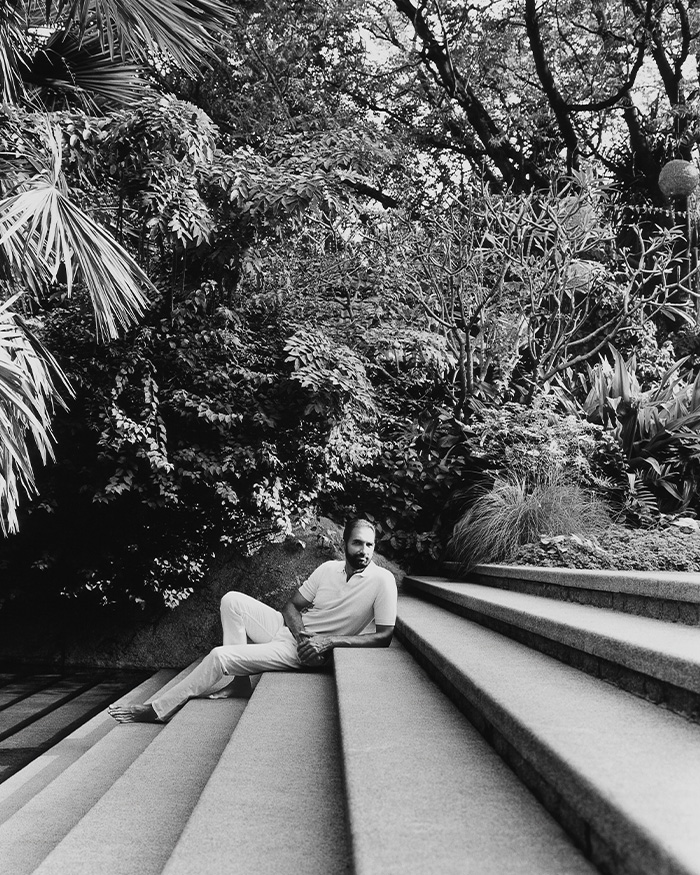

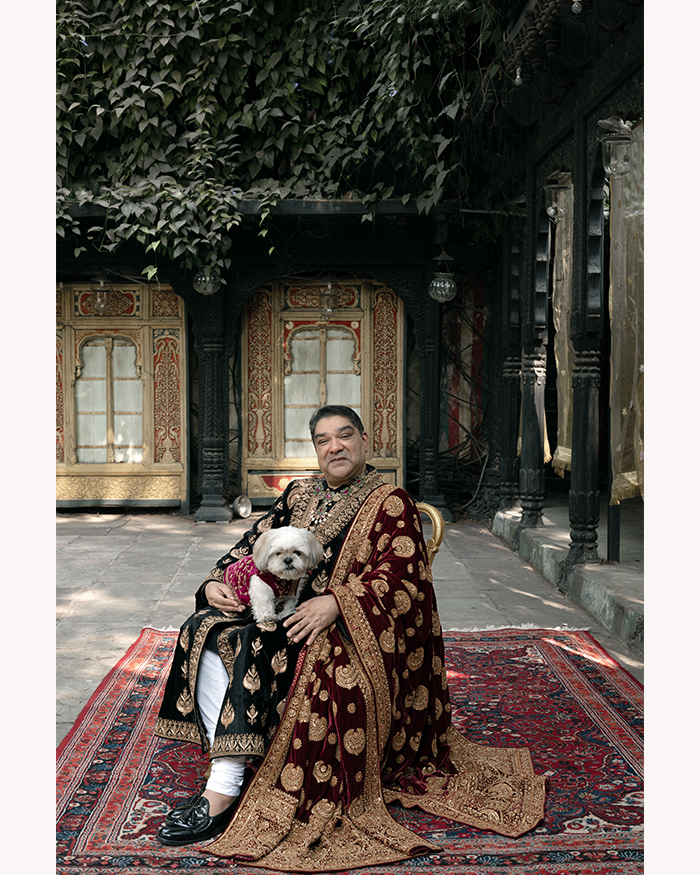

The Mullicks are thoroughly modern, much like you and me. Brotindro Mullick is an advocate at the Kolkata High Court. Sujata works in the social sector with human rights, social justice, gender and women’s empowerment. They are well-travelled and unpretentious, usually avoidant of the press. Their decision to invite us in is an exception, prompted in part by a felicitous coincidence: ELLE DECOR India’s 25th anniversary aligns with their own 25th wedding anniversary. Their modesty is astonishing when you consider what surrounds them. Just off Muktaram Babu Street, their address is one of the most recognisable landmarks in the city’s historiography: Marble Palace. Its halls are dense with paintings, sculptures and curios that crossed oceans to arrive here. The air is heavy with legacy, but also with a warmth that disrupts the condescending stereotype of the Bengali babu.

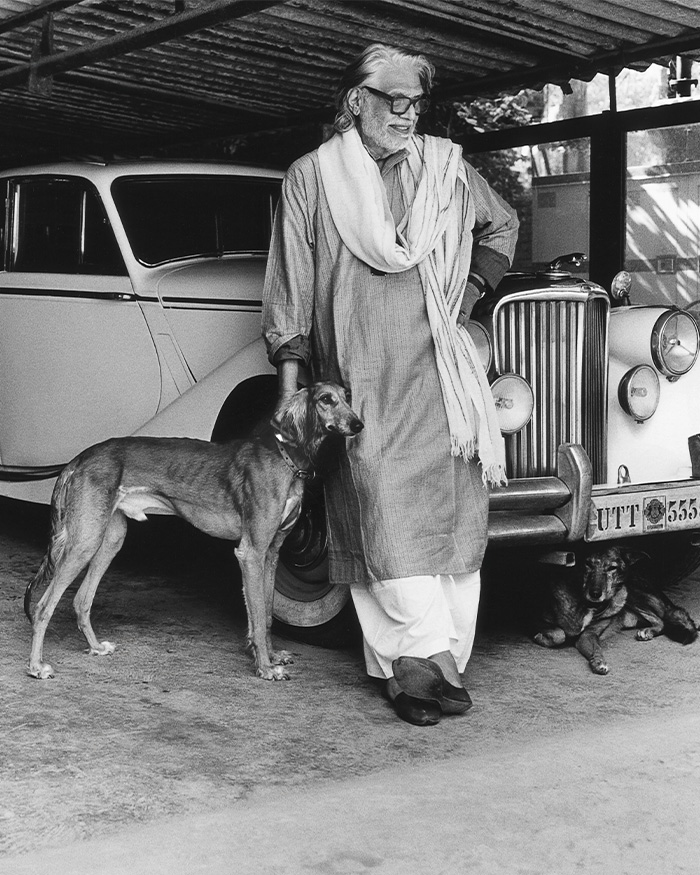

Across India, a narrow image of the Bengali elite persists, fuelled by colonial ridicule. In paintings, popular prints and literary satire, the babu appears as a grotesque hybrid: overdressed, over-ornamented, drenched in imported luxury and dubious morals, yet weak in resolve. This figure, part thwarted classical gentleman, part “effeminate” native, was central to colonial humour and later to a nationalist middle class eager to distance itself from feudal excess. The life-world that emerges from Marble Palace is almost diametrically opposed to that caricature. Brotindro and Sujata inhabit roles that invert the archetype. Even within the house, their language is one of stewardship and responsibility. They stand as a living antithesis who are, in habitus and vocation, closer to public servants than to decorative relics of a vanished class. The family history that brought them here begins far from North Calcutta, on the banks of the Subarnarekha river. The Seal family were prominent banik (bankers and mercantile traders). During the Mughal rule over Bengal, Jadav Seal, an early ancestor of Brotindro, was awarded the heridetary Mullick honorific, symbolising the family’s stature in the community. Over generations, the Mullicks have carried their title across Saptagram, Hooghly and Chinsurah before settling in Govindapur (one of the three villages that formed the foundation of Kolkata). Their shift inland was motivated by the need to escape Maratha raiders whose depredations still reverberate in Bengali lullabies. In the late 17th century, they moved away from Govindapur to create space for the new Fort William, tying the family’s story directly to the violent urbanism of the colonial capital. The compensatory land they received in Pathuriaghata became the stage for Babu Ganga Bishnu Mullick to emerge as a pivotal figure in the city. He built extensive trading networks across Bengal, the North-Western Provinces, and overseas in China and Singapore. Local memory, however, has preserved him more as a public benefactor. He is remembered for daily food distribution at a dharmashala, for funding alms houses during the devastating famine of 1770, and for installing native physicians in an era before formal dispensaries.

His son, Nilmoni, grew up in this milieu of commerce and charity. He created a temple to Lord Jagannath at a plot in Chorebagan. It became the family’s devotional centre and institutional anchor, and it continues to feed the poor today. The line between religious duty and social welfare was porous and part of the same moral economy.

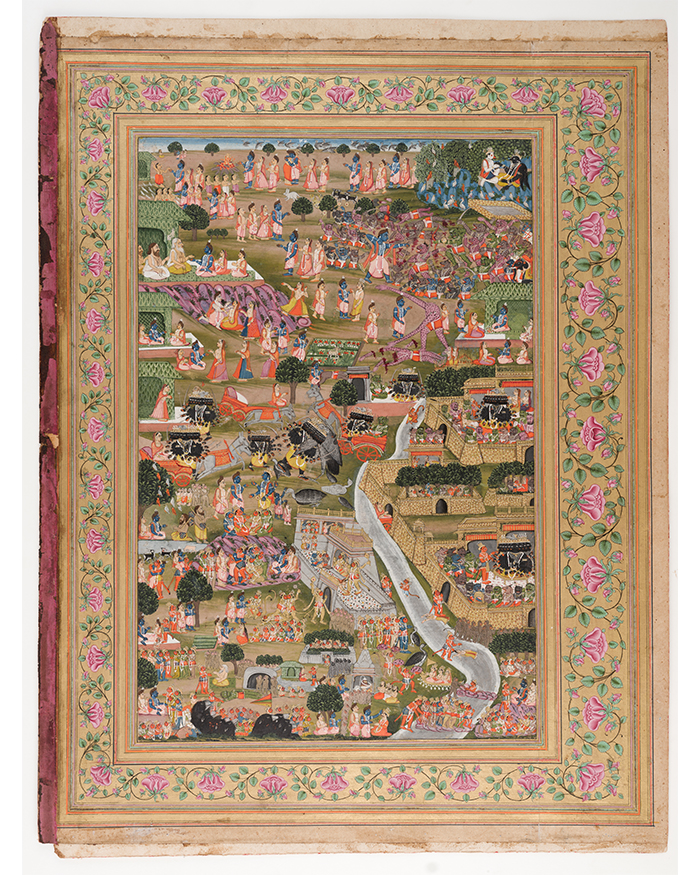

Nilmoni’s adopted son, Rajendro Mullick, extended these noble values, long after his father’s demise. As a teenager, he built a house adjoining the Jagannath temple in Chorebagan. He named it Nilmoni Niketan and conceived it as a museum and menagerie. It was created as a space where art from across Europe and Asia and exotic animals would be displayed for others to see. “The idea was never to build a private palace,” Sujata tells us, “He wanted it to be a museum for ordinary people to see a glimpse of the world.” During the famine of 1865, Rajendra reportedly fed anyone who came to his door, following in his grandfather’s footsteps. He penned a will aided by divine guidance that declares the house to be the property of Lord Jagannath. Today, the family, therefore, are not owners but Shebaits, custodians charged with managing the estate and preserving the rituals and extensive collections.

What “home” means under such conditions is therefore complex. For Brotindro, it is an amalgam of privilege and duty. He is clear‑eyed about the material comforts, but insists that Marble Palace is, conceptually, a museum more than a house. “It belongs to Lord Jagannath,” he says, “We were born here with that responsibility. We’re just here to look after it.” That sense of custodianship permeated even his childhood. Now, as the newest member of the trust, the attention has only intensified, “When I visit museums overseas, I feel proud and unhappy at the same time.” Proud, because the family’s collection is on par with many. Unhappy, because he is aware of the latent potential. “The founder wanted people to come and see his collection,” he says, “Now we have to think more from the visitor’s point of view.”

Sujata and Brotindro represent forward‑thinking ideas. The two met at the Rotaract Club (youth wing of Rotary club), a sphere of social service and self‑development that they both inhabit. She comes from a home where independence was lauded and educated women were the heads of the household. A world apart from the ancestral rules that bind the Marble Palace. Her belief in her judgement has encouraged her to question the rules around how women of the house dressed, their financial independence and their inclusion in rituals, in ways that were unthinkable a generation ago. For her, the way forward lies in distinguishing what is essential from what is contingent: “Culture has always adjusted to new needs.”

In the hands of the Mullicks, the Marble Palace resists being a vestige of a feudal past and becomes instead a place where the grandeur of history meets the exigencies of the present. They embody the conviction that cultural legacy is not about rigid preservation, but about responsible, purposeful evolution, ensuring the weight of the past serves to illuminate the path forward for the many, not just the few.