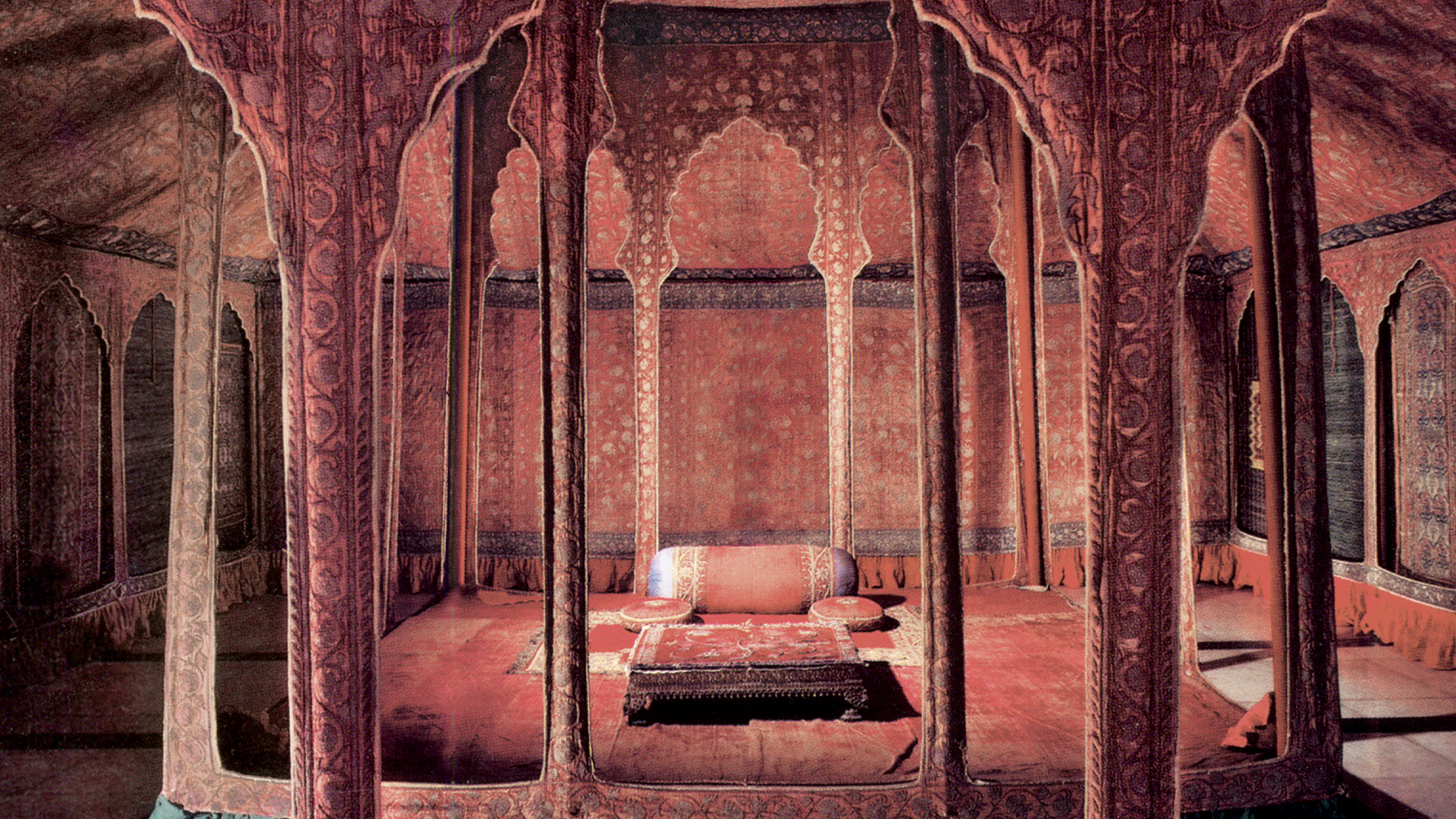

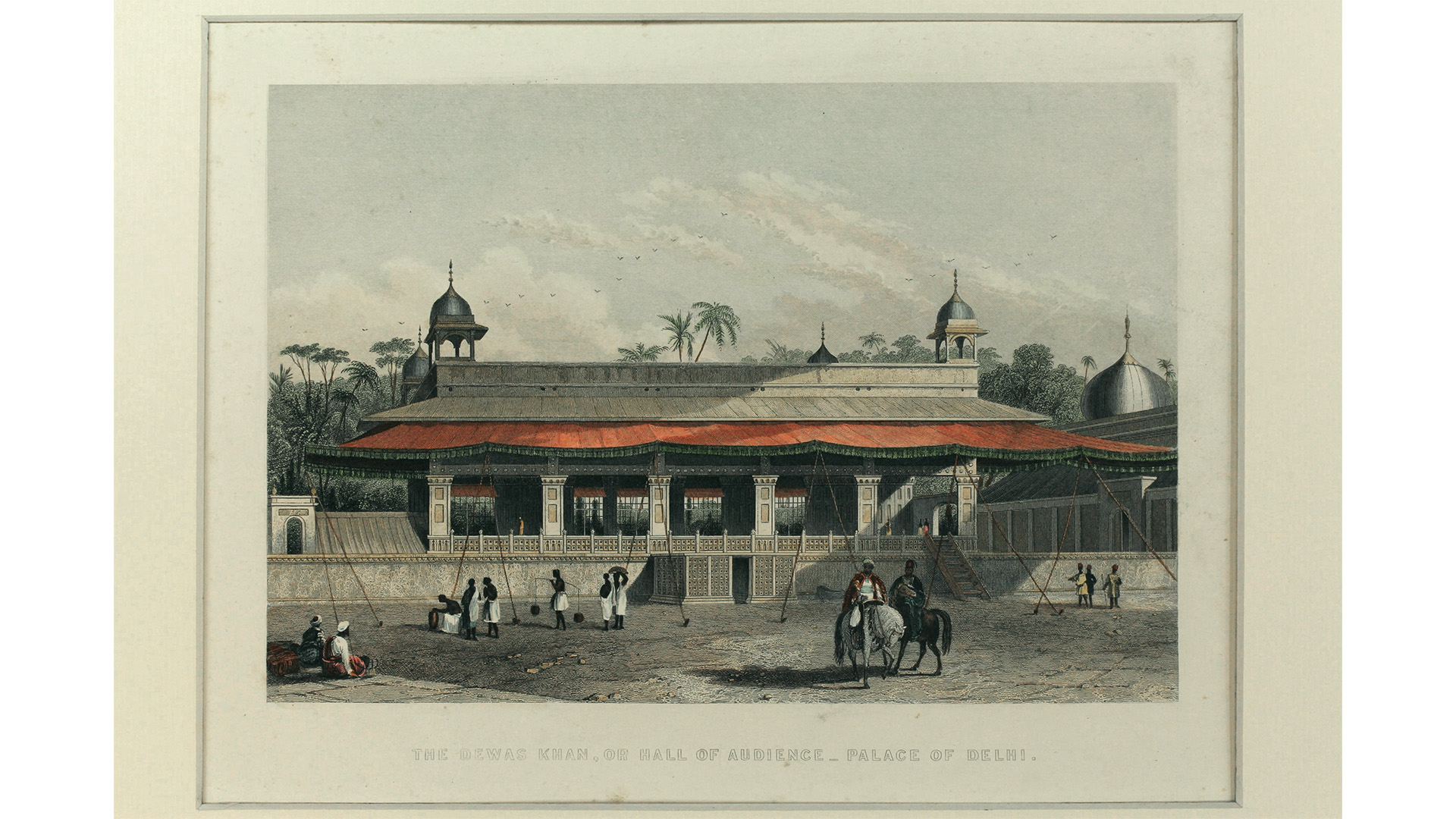

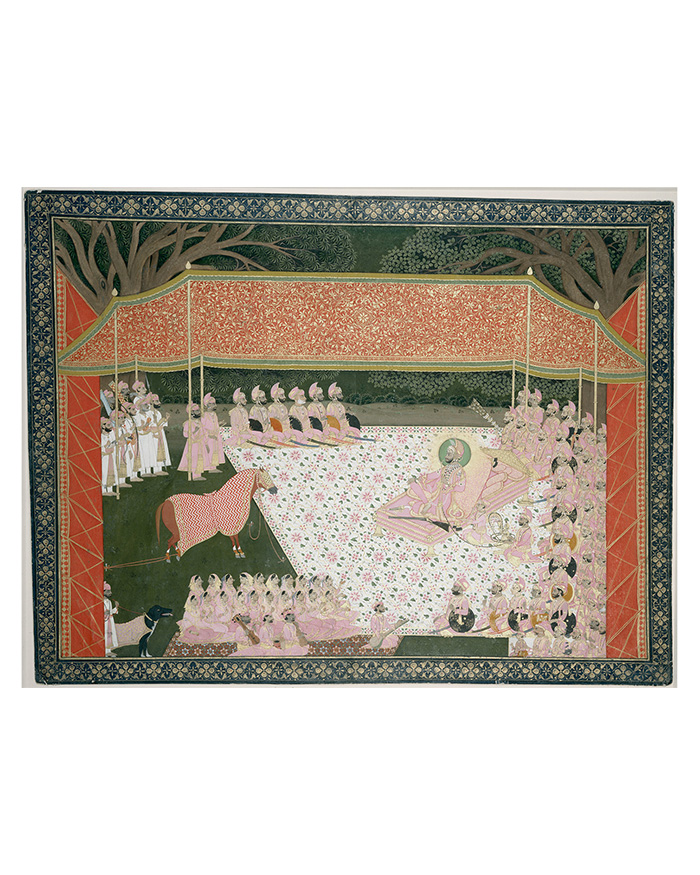

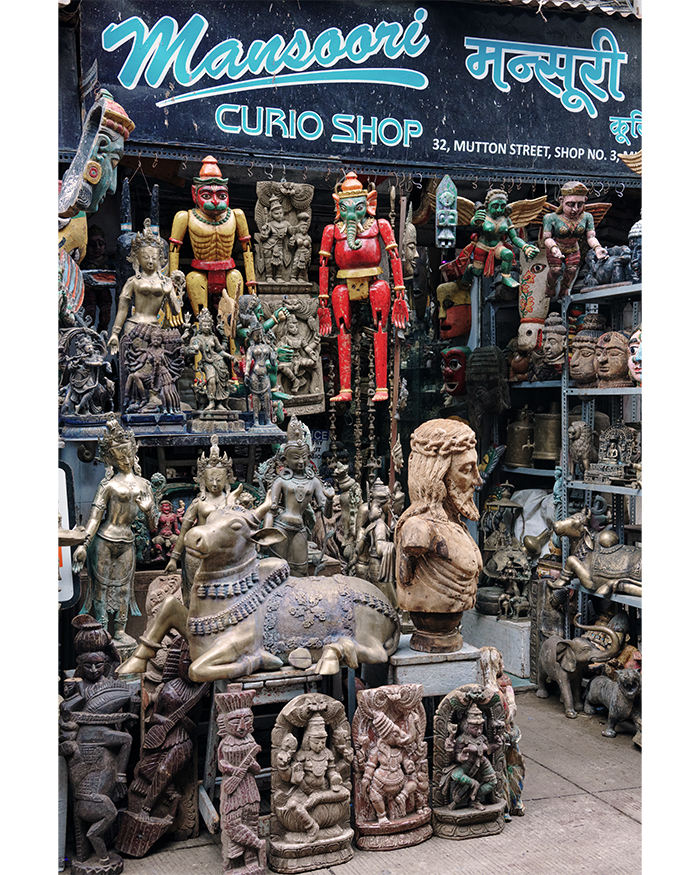

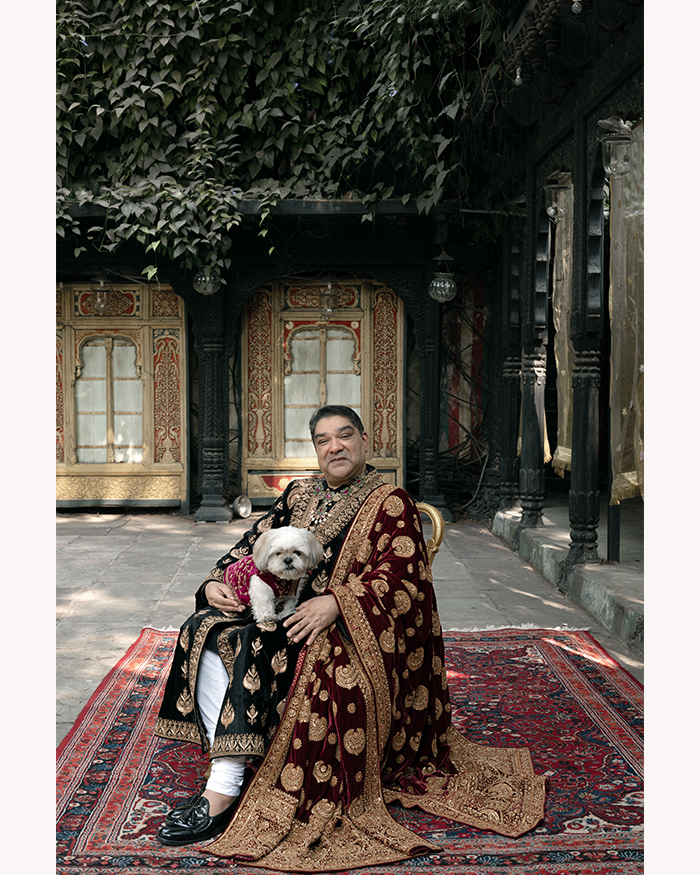

The idea of maximalism is often seen against minimalism. It is a binary that I reflect has deep biases, much like other such binaries which originate in West-centric approaches. But if you see how a massing with textiles takes place — whether in interiors or public spheres — not only in India but across Asia, Africa, and indeed many other parts of the world, we see how what we may perceive as minimalism has aspects of what we may perceive as maximalism, and the other way around. The Indian experience lies somewhere in between, and beyond, in the liminal spaces and interactions that take place not only in the relationship of objects, but in how they relate to the spaces they occupy and are occupied with. This apparent diversity creates a natural seamlessness of opposing and contrasting elements. We may also see this as some kind of balancing act, but it has its own logic and intelligence which is also beyond. I see what we refer to as such maximalist tendencies in the use of textiles then, as a great non-hierarchical way of assemblage, of organising, of art-making even, where the eye does not stop. One can reach a point of satiation, but there is always room for more! This is a lot like the Indian thali. Unlike a regulated system of courses in a Western meal, this offers someone eating the endless possibilities of discovering their own permutations and combinations based on individual preferences. We may think of this as excess, but I don’t see this in the wasteful way that we often view decadence in.

“It is also so when we choose how to use such fabric: to adorn, to decorate is an innately human impulse. It offers a way to communicate, to make things our own. It is also a way to venerate, to make something special, to give it ascribed meanings”