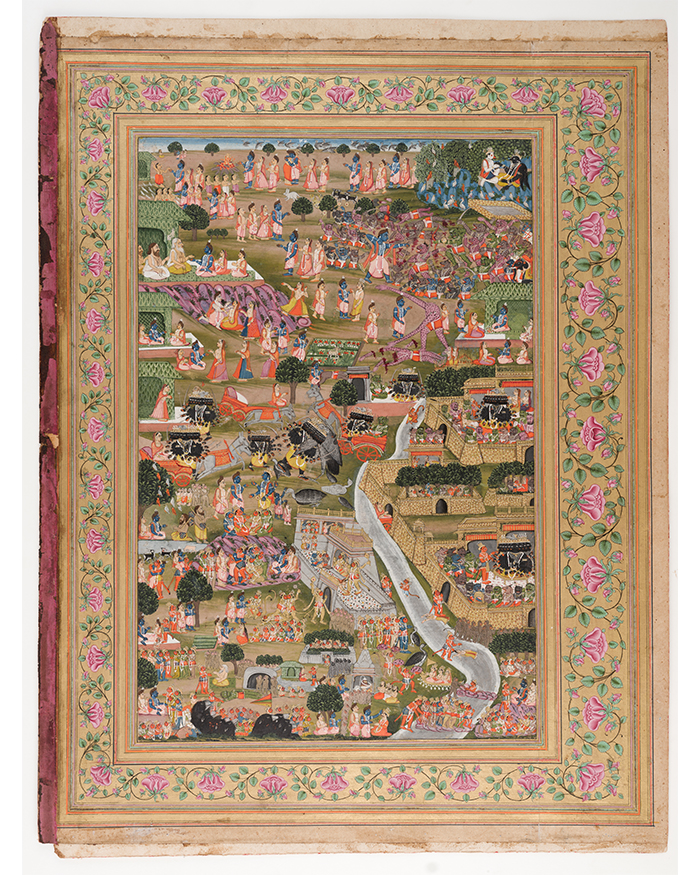

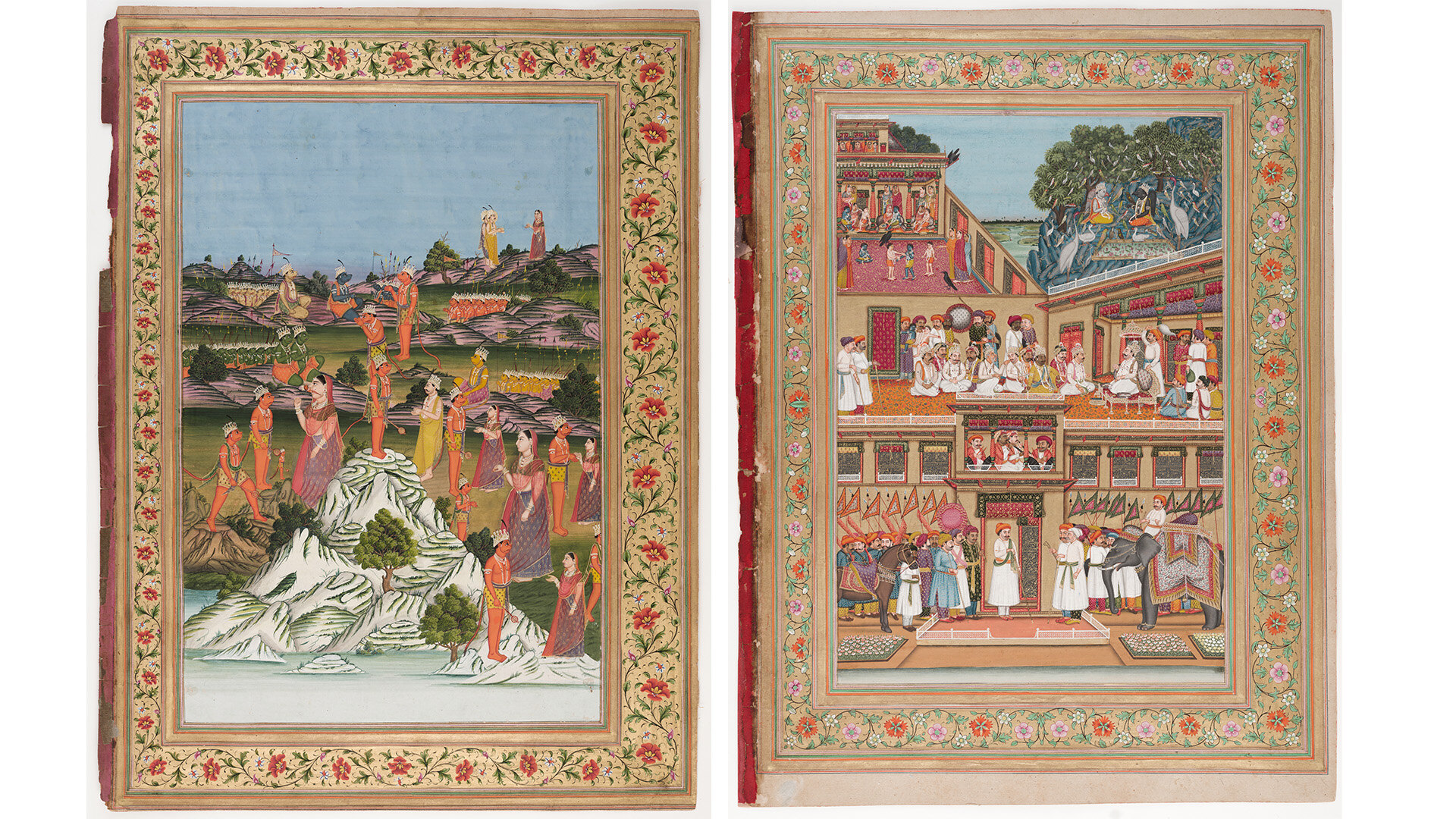

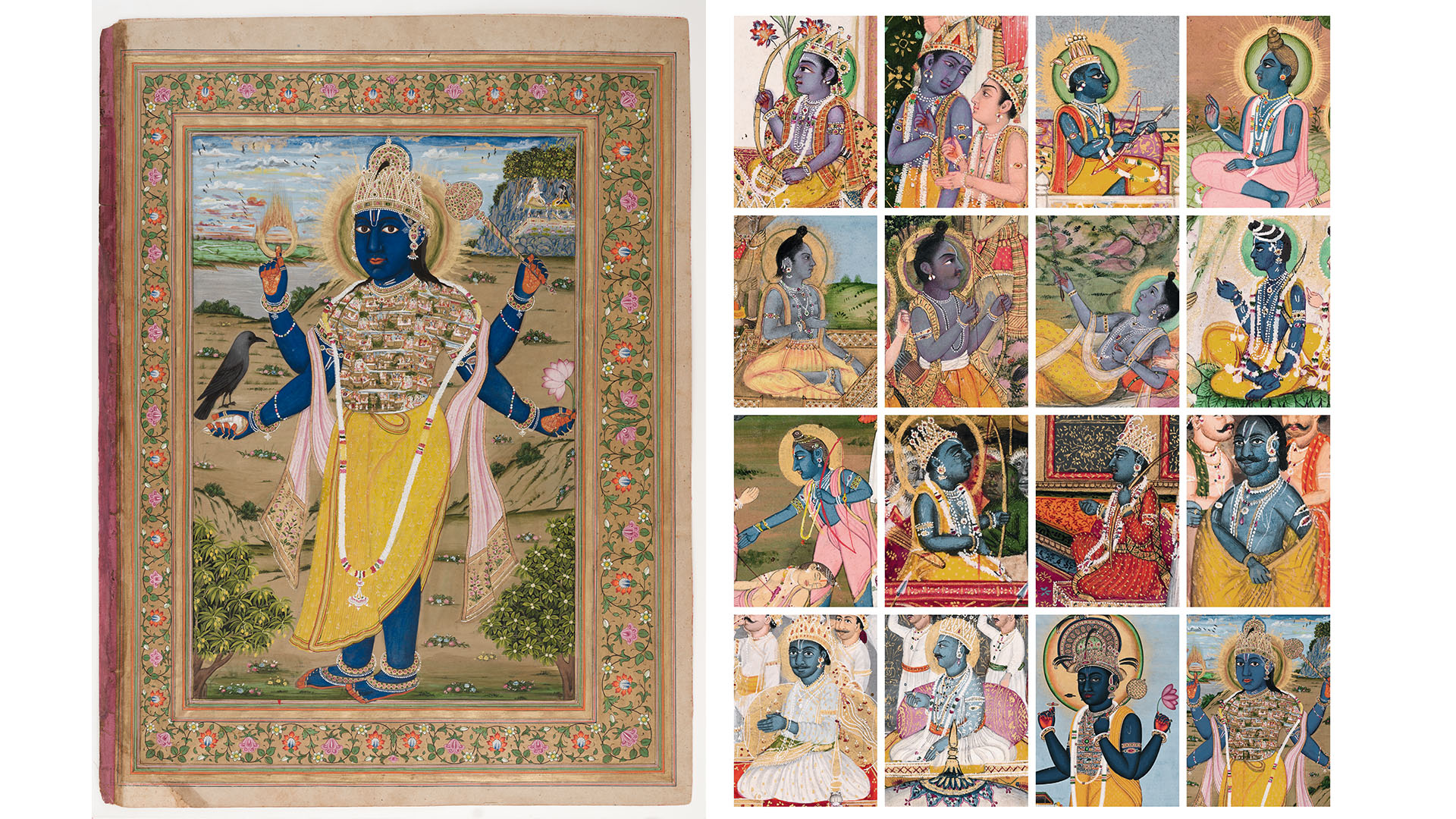

There’s a particular quality to work done carefully and meticulously — by hand, with care, detail after detail, meant to last for centuries — that transfixes each one of us that encounters it. The Kanchana Chitra Ramayana (Book of Gold) is one such work, which invites you to pause, look closer and find more to discover. Hundreds of years after its creation, this astonishing book continues to offer visual testimony to the untold mehnat of hundreds of painters, scholars and scribes, whose contributions live on within its pages. One of the most expensive manuscripts ever commissioned, the ‘Book of Gold’ was commissioned by the Maharaja of Benaras, who ordered that all 1,100 pages of the 7 volumes be richly gilded, and no expense was spared. The ‘Kanchana’ in its name comes from the lavish use of gold, which would be ground fresh every morning to be mixed into pigments to line the verses, and burnish 548 full-colour paintings that accompanied each page of text, and ‘Chitra’ meant that every page of text was to have a corresponding image illustrating it.

When the royal scion of Benaras, Udit Narayan Singh, first conceived the mammoth project in 1796 — mere months after ascending the throne — there was no precedent to such an ambitious undertaking, which would eventually take 18 years to be completed. Udit Narayan’s patronage ensured that the ancient city turned into a hubbub of activity for decades to come, with master artists from various ateliers across India arriving in Benaras, setting up karkhanas to bring his vision to life. A glance at the Kanchana Chitra Ramayana offers a look at a multiplicity of styles, characteristic of individual schools of miniature paintings, from Murshidabad, Datia, Faizabad, Lucknow, Awadh, Jaipur and the Mughal court. Art historians credit the project with bolstering the tradition of miniature painting at a time when the art form was in decline. The timing of this maximalist cultural endeavour tells its own story. By the late 1700s, Mughal patronage was on the wane. The East India Company had signed treaties with Hindu rulers, including Udit Narayan Singh, forcing them to renounce most of their authority.

No longer permitted to maintain his own army, mint currency, or preside over the judiciary, the Benaras royal turned to the cultural sphere to retain the last vestiges of his influence over his republic. He began by building visible architectural projects, constructing large water tanks, pleasure palaces, extensive gardens, and towering temples to Ram in a city traditionally associated with Lord Shiva. The Benaras dynasty’s interest in Ram was not unique to the time. As Mughal authority crumbled, a number of Hindu rulers turned to Ram not just as a deity worthy of worship, but as an Indic model of a righteous and victorious ruler. The commissioning of the Kanchana Chitra Ramayana helped cement this narrative because it relayed the story of Lord Ram’s glorious rule in Awadhi, the language of the people. While the Ramayana itself has been in circulation for more than two millennia, written in Sanskrit and attributed to Sage Valmiki, millions of people in North and Central India are only familiar with the version of the epic retold by the saint-poet Tulsidas, who portrays Lord Ram as a divine, infallible being within his Ramcharitmanas.