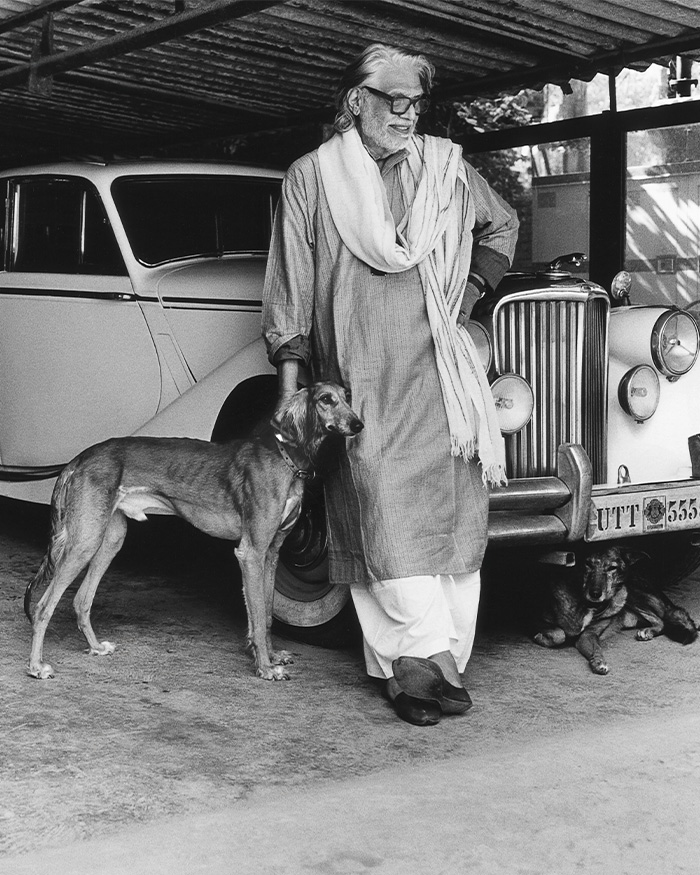

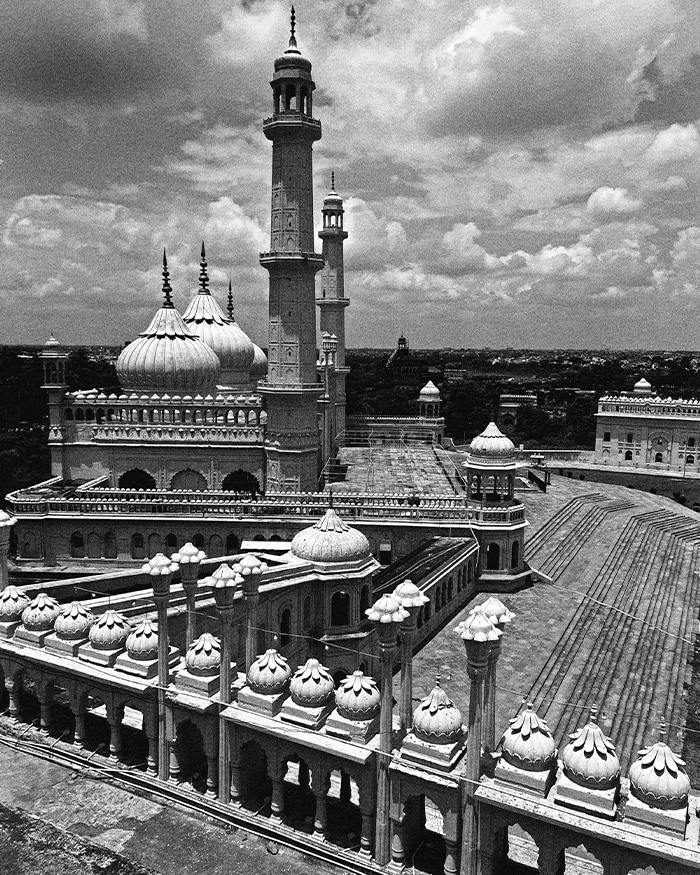

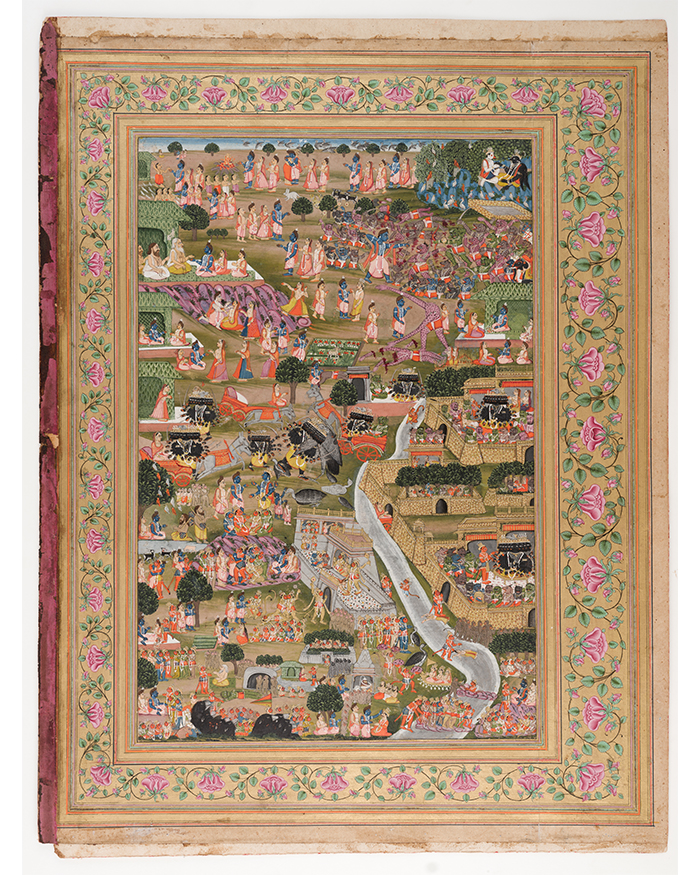

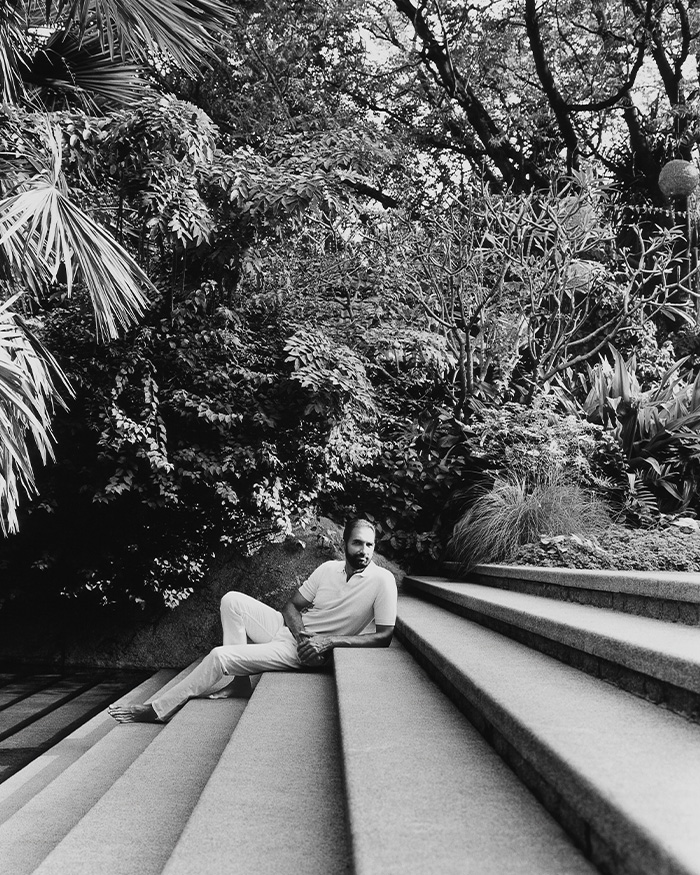

Some cities train the eye to look for monuments. Lucknow trains it to look for conduct. A slight pause before a reply. Humour folded into a sentence. The courtesy that makes room for another person. In Lucknow, refinement is culture, built slowly, transmitted through language, music, dance, poetry, demeanour and craft. Muzaffar Ali’s work carries that inheritance. His maximalism is not the maximalism of scale. It is the maximalism of depth: a world where poetry, costume, choreography, light and silence speak to each other, and where a pause can hold as much power as a flourish. If maximalism today is routinely reduced to surface, Ali reminds us that India’s richest form of more has always been made from meaning. In the conversation that follows, he speaks about Lucknow as a sensibility, cinema as composition, and refinement as a form of cultural intelligence.

How does Lucknow cultivate maximalism?

It has a deeper sense of understanding and feeling situations. The deeper the feeling the greater the sense of the maximal. Here one thing leads to another, till you create an anjuman, a congregation of people and ideas. These feelings are getting eroded by consumerism and film can be one way of recreating them for everybody.

What is Lucknow’s most prominent contribution to Indian maximalism?

I would say dance. Dance includes everything, poetry, music, costumes. We need to celebrate and conserve dance before it is degenerated by crass commercialisation in films and stage shows.

Your films challenge the idea that maximalism equals excess. What does refined, detail-driven maximalism look like on screen?

Elements and technology that enrich a frame with truth is a patient search. Understanding and creative use of light and colour is the artistry of tomorrow and the foundation of genuine maximalism. The art is what not to use to give power to what has to be used. Being specific is important and a necessity. Creative use of light comes from understanding details which tell the story, adding meaning to the layers that have purposely been used by the artist. It touches the audience differently in each exposure. This makes art addictive and creates repeat viewing.