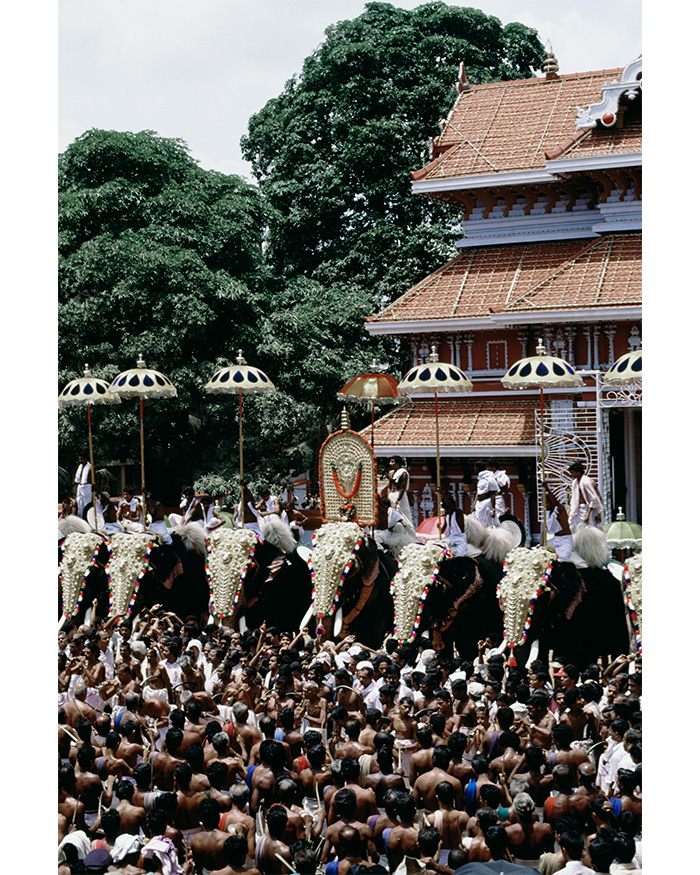

India has always blurred the lines between ritual, performance and sport. Each is an offering, a form of worship — to gods, to nature, to community. Across its many regions, moments arise when hundreds, even thousands, move together in colour, rhythm, devotion and competition. Beyond performances to be watched; they embody collective memories, beliefs and beauty.

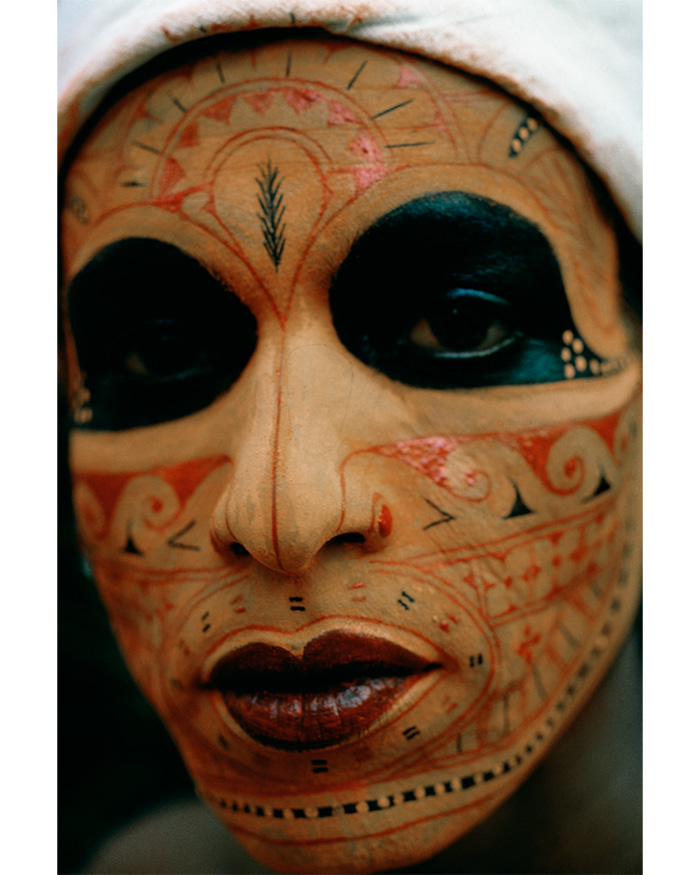

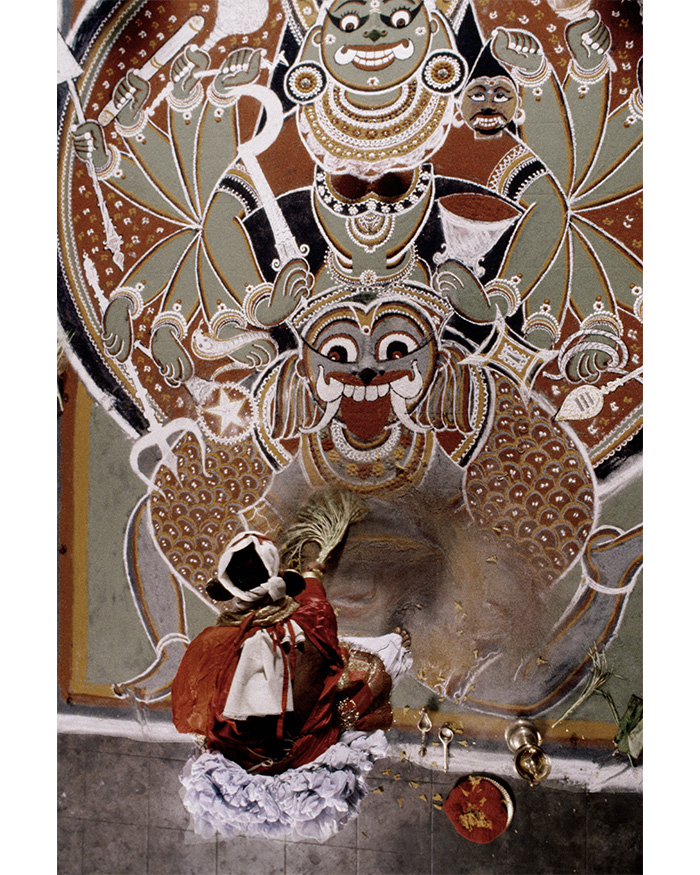

In the lush greens of North Kerala, as dawn seeps into the coconut groves, drums begin to thunder. The Theyyam performers — men transformed into gods — emerge from the sacred groves painted in red, black and white. Their faces are no longer their own; they are divine. The body becomes a canvas of intricate design, the headgear towers like a temple spire and as the chenda beats grow urgent, the man beneath disappears entirely.

"The goddess is both born and unmade in that act — a lesson in the cyclical nature of all existence. Creation, destruction, renewal; art that is philosophy"

Mallika Sarabhai