Produced by Mrudul Pathak Kundu

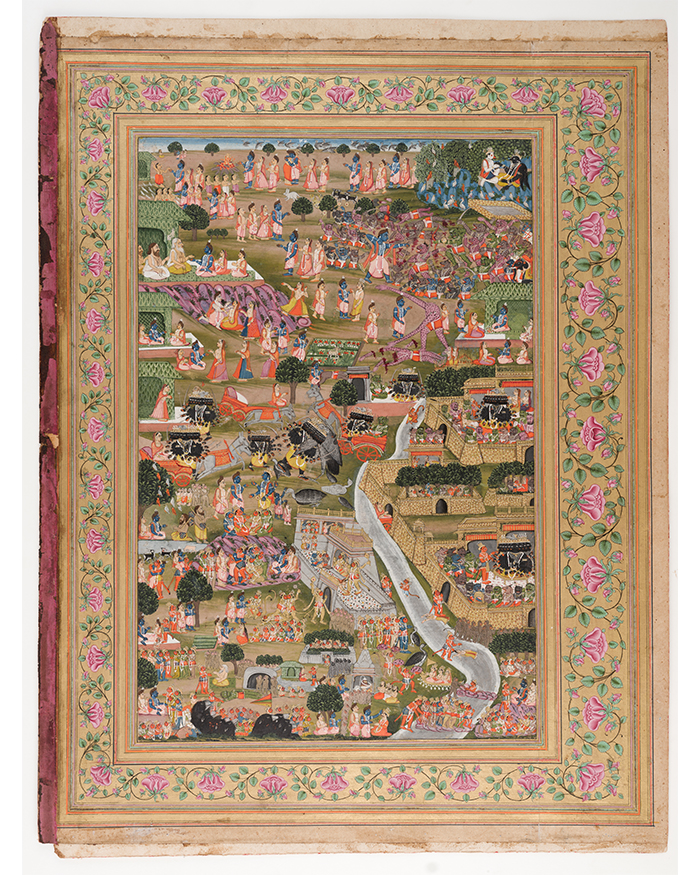

Hyderabad’s story is often told through its diamonds and its Nizams. A land that gifted the world some of its most expensive, rare gemstones. An economy that rivalled small European nations. And a Nizam whose wealth was estimated at two percent of the American GDP during his time. Mir Osman Ali Khan, Asaf Jah VII, the last Nizam of Hyderabad, was one of the richest men of his era and the palaces of Chowmahalla and Falaknuma staged his power. Heads of state and imperial guests were hosted at the 32-acre Falaknuma Palace, perched on a hill above the city. With 60 rooms and 22 halls, it housed the world’s largest collection of Venetian chandeliers (including 40 Osler pieces), lined with a Windsor-style library of more than 5,000 books, an unrivalled jade collection and a 108 ft dining table that seated around a hundred guests. He ruled from the Chowmahalla Palace which sprawled 45 acres with four palaces. His fleet of cars included a Rolls Royce Silver Ghost of 1912 among many other rare luxury cars.

While the wealth, the palaces, the land and kingdoms are always remembered in the names of men who invaded or inherited them, the afterlife of many such empires has been carried by women — women like Princess Esra Birgen Jah. Born in Turkey to a prominent and respected Ottoman family though not directly linked to royalty, Princess Esra (then Esra Birgen) chose to marry Prince Mukarram Jah (grandson and designated successor of Mir Osman Ali Khan, the last ruling Nizam of Hyderabad). She stepped away from India when the marriage ended, but returned decades later, not to live in its splendour, but to rescue what was left of it. Cut to the present, it has been 15 years since the Falaknuma Palace was restored and relaunched by Taj Hotels Resorts and Palaces. 25 years since Princess Esra initiated Falaknuma’s restoration, 29 years since she returned to the country to confront the family’s crumbling palaces and 66 years since she first came to India as a young woman marrying into the Asaf Jahi dynasty in 1959. But it is the period from 1947 till her marriage that shaped the landscape she would eventually inherit.

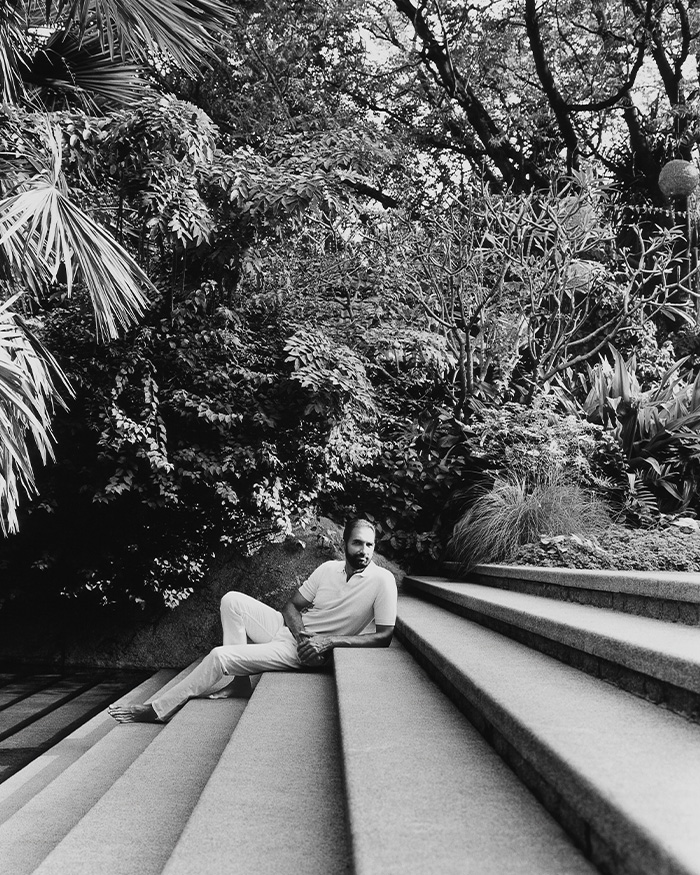

The palaces fell into neglect when sovereignty ended and with the abolition of privy purses in 1971, the last supports of royal life disappeared. Today she divides her time between India and England. I meet her at the Games Room in the Falaknuma Palace. She wears a tissue gold saree, “I am not a maximalist,” she tells me. “But if there was ever a programme on minimalists, I’d fit right in,” she continues. Her worldview is shaped by living across continents, and coming of age in post-war Europe. She attended boarding school in England and later studied architecture. It was not only the moment of mid-century modernism, but also a time of social upheaval and anti-elitist sentiment. “In those years in England, we were against rich people for the poor,” she recalls. “If you over-jewelled, they called you a Dowager Duchess.”

“I am not a maximalist. But if there was ever a programme on minimalists, I’d fit right in”

- Princess Esra Birgen Jah