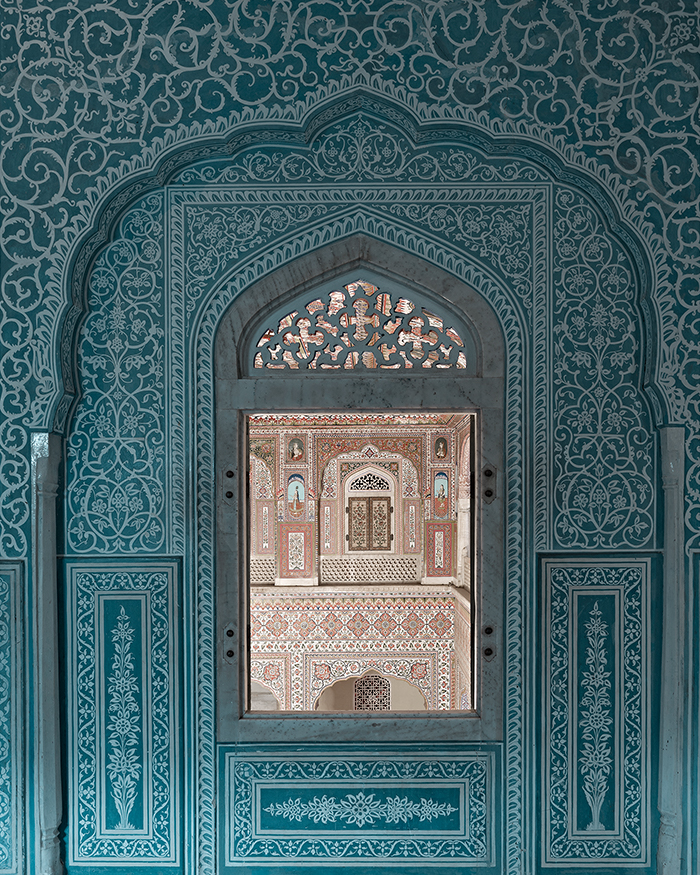

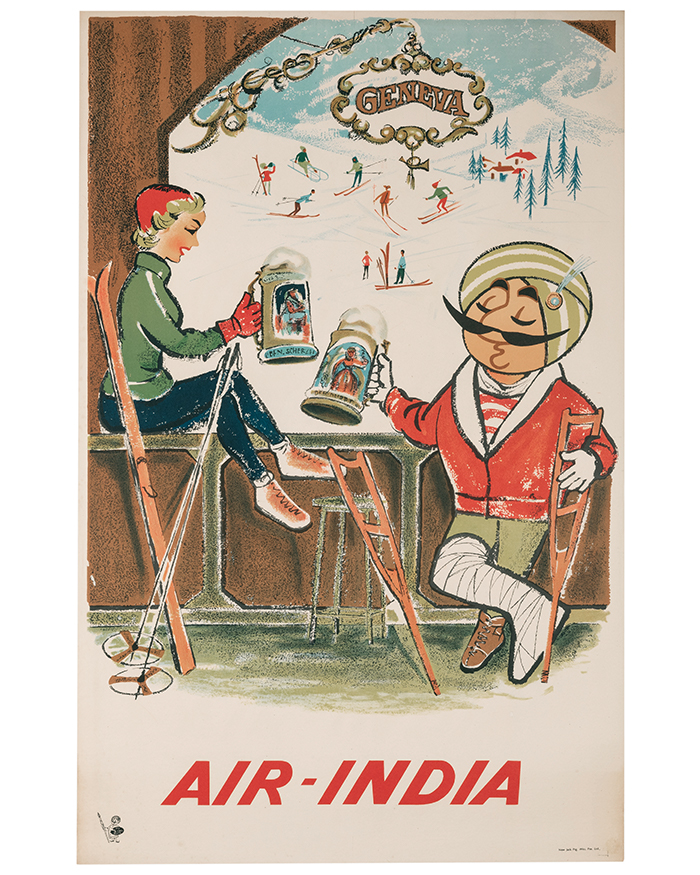

The old Air India Maharaja lounge smells of jasmines and sandalwood. In this in-between world of airports, where time and place are distilled into concepts, at once amorphous and ever-present, the lounge offers a sanctuary. It locates the traveller in an experience. It reminds them of their place in a history that is still being written. In India, hospitality is, and always has been, a function of feeling. Our culture is imbued with a deep sense of collective responsibility that flows from centuries of connectedness. At the heart of this web of care is the family. Parents are revered as living gods and guests are recognized as divine visitors. Even our doorways are thresholds of ceremony. Adorned with vibrant rangolis and fresh garlands, they mark the sacred welcoming of guests into the ghar, ready to receive not just a person, but the abundance they represent. To serve is thus a matter of immense pride. No one leaves an Indian household hungry. Hospitality is everywhere — at border crossings and bus stops, in havelis and mud homes, on trains and lake-boats.

“Is hospitality in India an act of trade or care? Few would say its spirit is for sale. The care invested is genuine, rising above transaction”

- Amitabh Kant