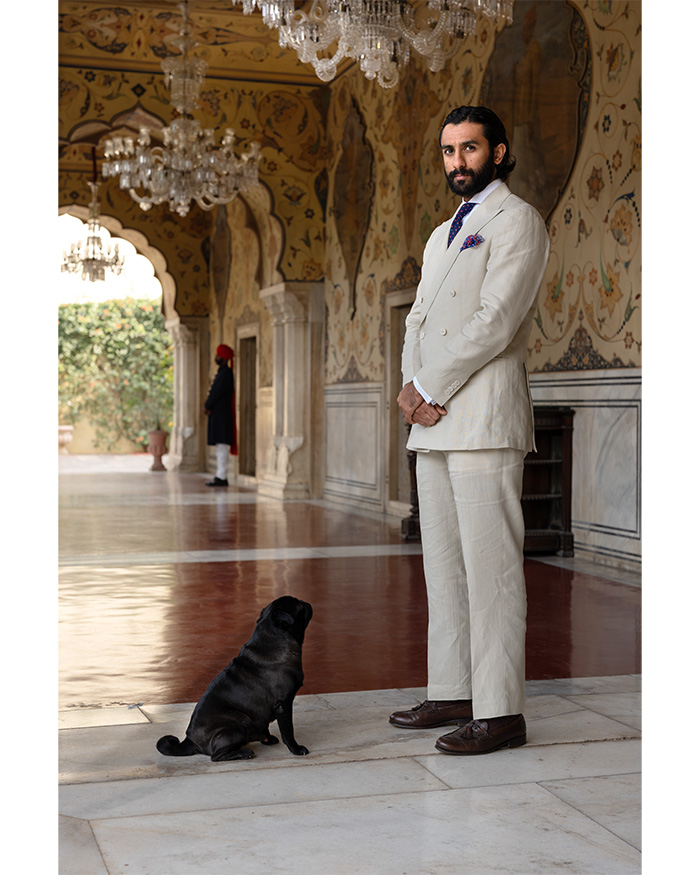

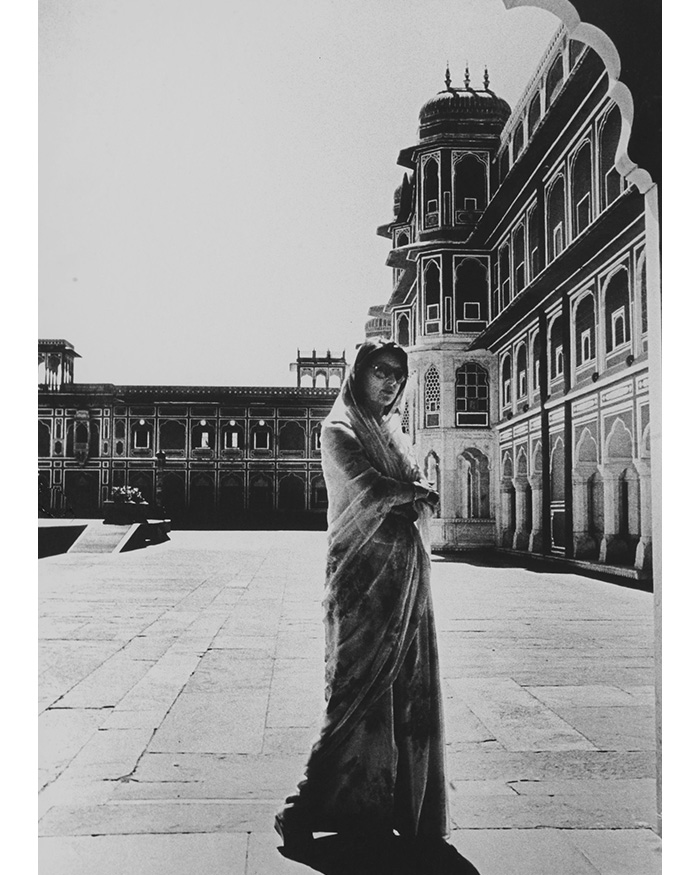

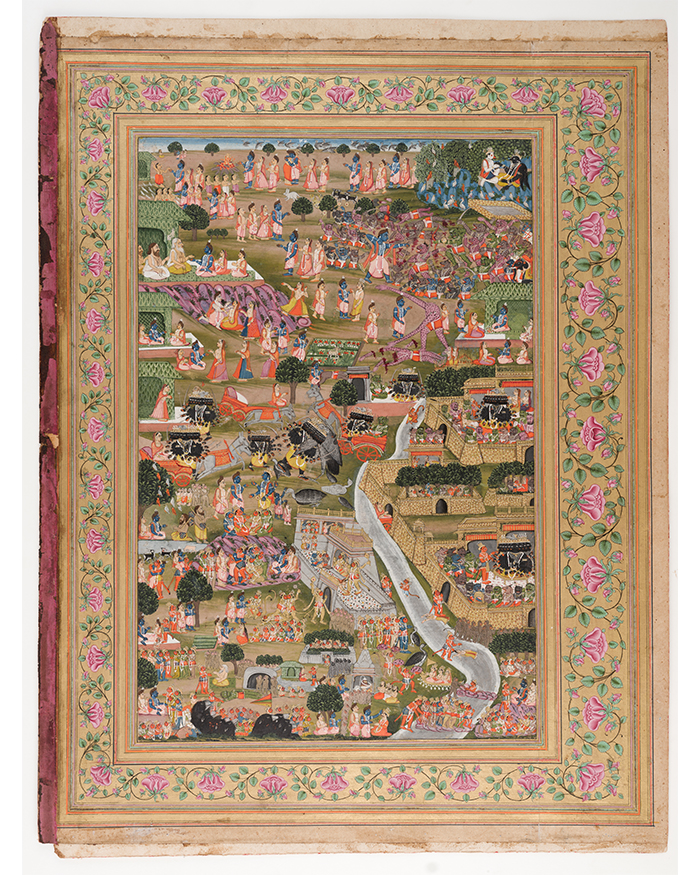

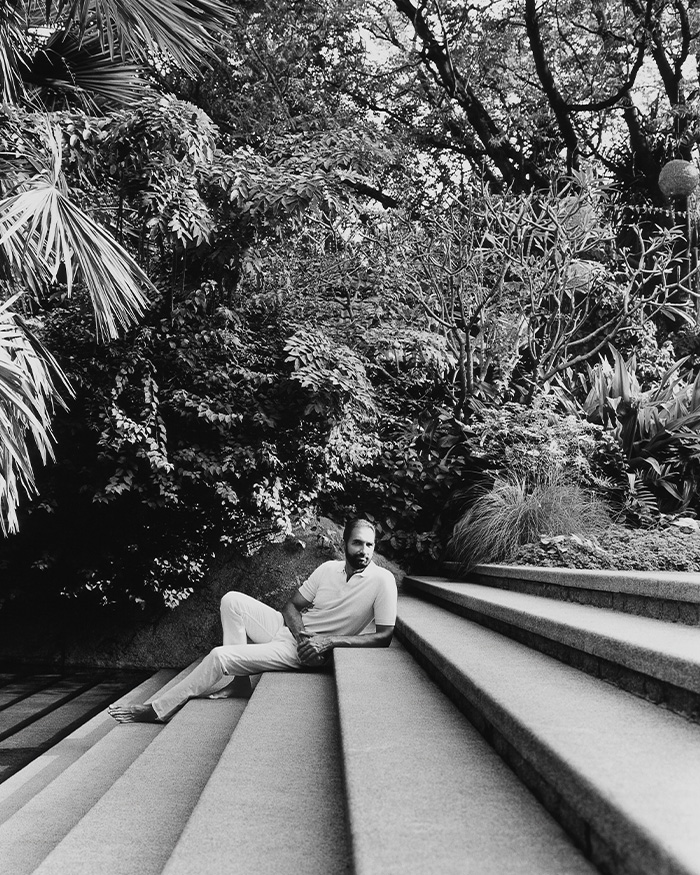

All of 27 years old, in the league of the Generation Z, a descendant of the erstwhile clan of the Kachhwaha Rajputs and crowned at the age of 12, His Highness Maharaja Sawai Padmanabh Singh of Jaipur stands at rare crossroads: born into history, living in the present and shaping a future. His influence has little to do with the throne, however. The modern maharaja’s eminence is perhaps multidimensional — vocalised on social media as a public figure, frequent appearances on magazine covers, attendance at galas and red carpets, and of course, embedded into Jaipur’s crafts and community building, restoration plans, managing the affairs of the City Palace, Jaipur and trusts and commanding the world-admired legacy of polo as a captain — all a natural part of his world. His influence also emanates from his ability to articulate why Jaipur matters today, why Indian maximalism is not confined within a palace and why it must exist as a larger worldview. Because what becomes of royal inheritance in a democracy where formal titles and imperial powers do not exist anymore? When the Indian government abolished royal titles under The Constitution (Twentysixth Amendment) Act, 1971, the reality of royalty shifted immediately from a political institution to a cultural authority. “I have grown up watching how my grandfather, through his military service, and my mother, through her work in public life, have treated heritage as a duty towards others, not just as a family story,” he says, often belovedly known to many as Pacho, who inhabits the colossal sprawls of the City Palace, Jaipur that rose to life in 1727 built by Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II, as his private home as well as a public landmark. The sky, the land, the air feel mesmeric even today.

“I have grown up watching how my grandfather and my mother have treated heritage as a duty towards others, not just as a family story”

- His Highness Sawai Padmanabh Singh of Jaipur