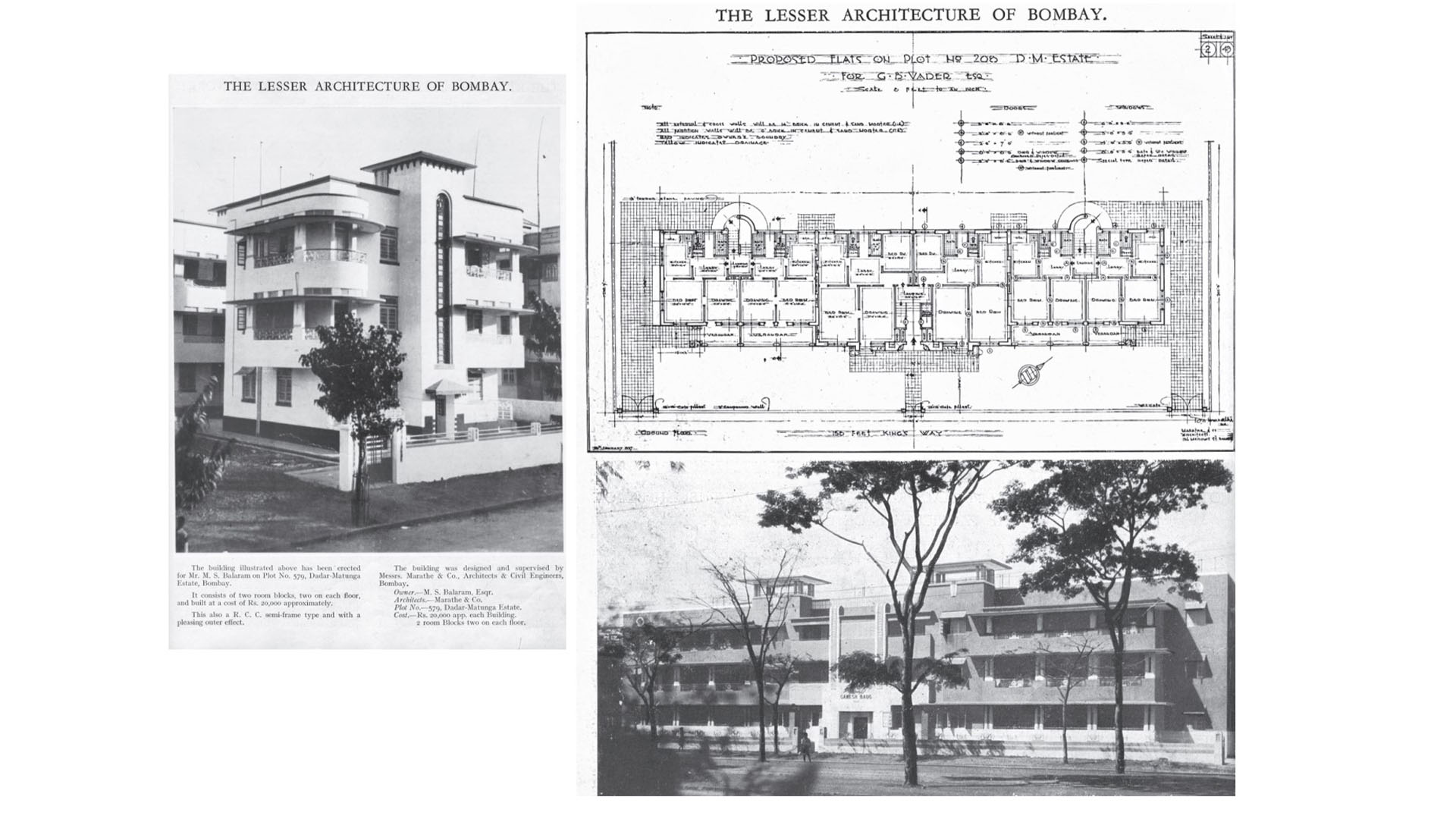

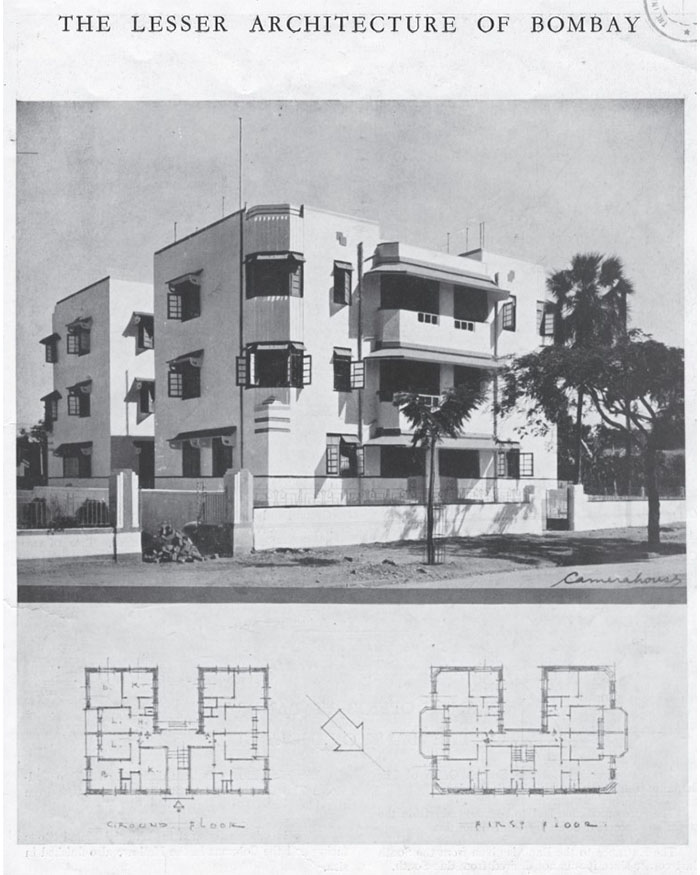

An out-of-order medical cross blinking at random intervals. Loose polythene wrappers stuck on cast iron grills. Last night’s laundry hung out to dry. This was a facade like no other. But if you squint past these details, it was clear as day. We had struck gold. Art Deco, in Dadar. How did I never notice it?

It’s true that you know the least about your own neighbourhood. And in mine, it is far too easy to let the noise overwhelm you. Like most newly minted Mumbai residents, I too was under the impression that the 1920s architectural movement was only confined around the Oval Maidan. How did it travel across the islands and wind up in the chaotic bylanes around Shivaji Park? As we walked around, the story took unexpected turns.

"While some of us call this tree-lined neighbourhood home, with its hubbub and character, it becomes pertinent to ask if architecture, only of a certain aesthetic appeal, deserves to be cherished?"