“Everyone who has purchased the art is someone who doesn’t care about Sabyasachi,” the designer begins. Surrounded by the imagery of the grand maximalist world that Sabyasachi Mukherjee has built, the statement feels hard to digest. When I step into Nilaya Anthology, located in Mumbai’s mill district, the first space dedicated to his art foundation, a lingering sense of cynicism takes hold. What does it mean for art to be supported by one of the most talked-about figures in the country? It turns out, this was a thought that crossed Sabya’s mind as well. He admits, “I made sure to show it to the right people and the right directors. I asked them all: What do you think about this art? Are you buying it because of its platform?” They told me, ‘Don’t kid yourself. The art is bigger than you.’”

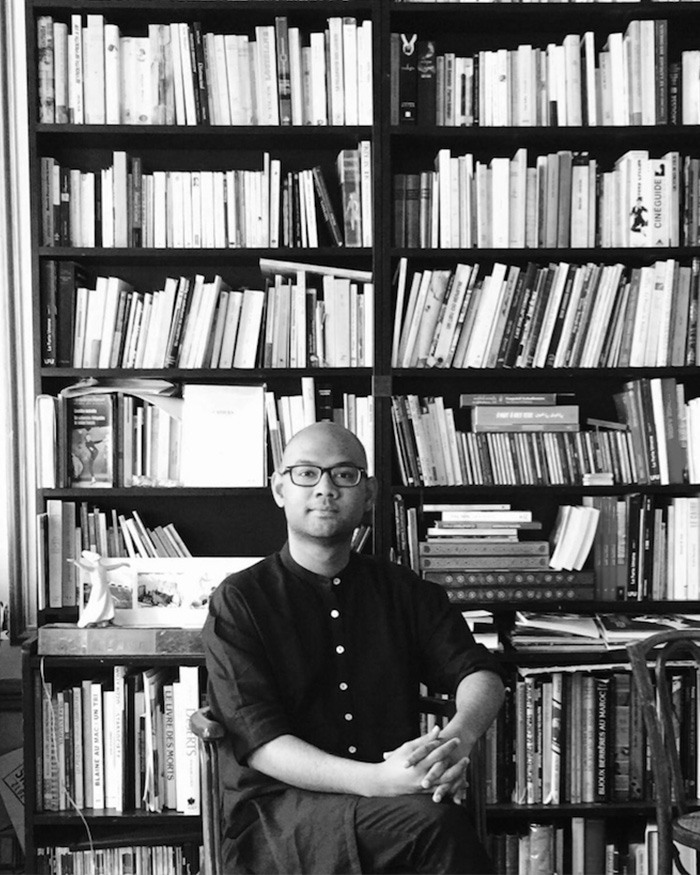

The Sabyasachi Art Foundation, established by him in 2014, aims to make art and culture economically sustainable. It provides underprivileged artists from Bengal with a safe space to hone their craft, fostering a cultural dialogue between the creator and the patron. At Nilaya Anthology by Asian Paints, the foundation finds its first gallery, showcasing the artworks of Atish Mukherjee — an artist who stands in stark contrast to the brand’s grandeur. Within the 100,000 sq ft space, the ground floor hosts the gallery. Atish’s art is urgent and hauntingly beautiful, layered with bold, unflinching colours. Atish is a man of few words, allowing his work to speak for him. Against the backdrop of blood-rust walls, his figures leap off the canvas, drawing you in. Sabyasachi shares, “I wanted to use my platform to give him the right springboard. But I knew in my heart that he would eventually become bigger than the foundation, and the foundation would need him more than he needs it. I just wanted to help him take that leap of faith. The truth is, people will recognise him, not me.”

“Success for me is that the artist is visible, and we remain invisible” — Sabyasachi Mukherjee